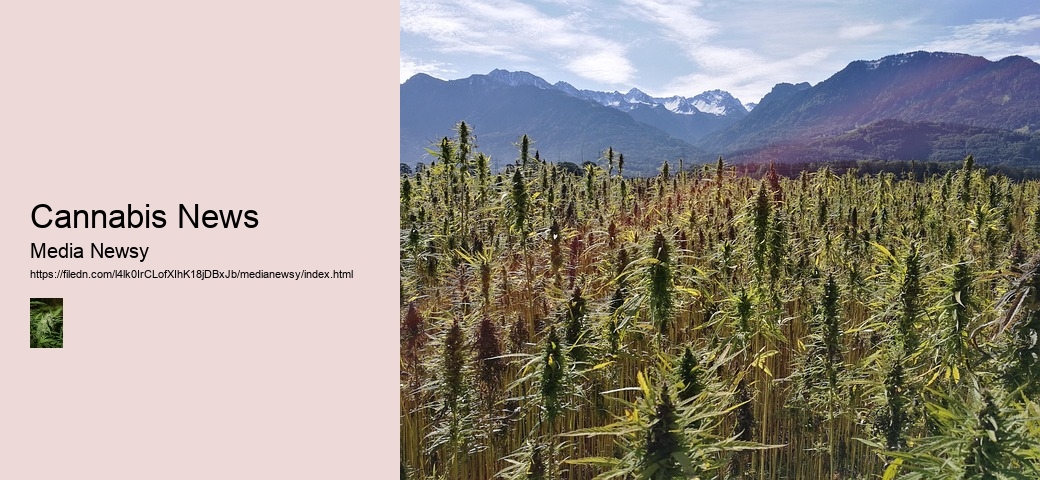

Legalization Updates for Cannabis News

The world of cannabis legalization is constantly evolving, with new updates and changes happening all the time. From new laws being passed to regulations being updated, staying on top of the latest developments in the industry is crucial for both consumers and businesses alike.

One of the most recent legalization updates in the United States comes from New York, where Governor Andrew Cuomo signed a bill into law legalizing recreational marijuana for adults over the age of 21. This move makes New York the 15th state in the country to legalize cannabis for adult use, marking a major milestone in the fight for nationwide legalization.

In addition to New York, other states such as New Mexico and Virginia have also recently passed laws legalizing recreational marijuana, further expanding access to cannabis across the country. These changes not only provide new opportunities for businesses in the industry but also offer relief to individuals who have been disproportionately affected by past drug policies.

On an international level, countries like Mexico and Luxembourg have taken steps towards legalizing cannabis for recreational use, signaling a shifting attitude towards drug policy worldwide. As more countries embrace legalization, it is clear that the global cannabis market is only going to continue growing in the years to come.

Overall, staying informed about legalization updates is key for anyone involved in the cannabis industry or who simply wants to stay up-to-date on current events. By following these developments closely, we can better understand how attitudes towards cannabis are changing and what this means for society as a whole.

Medical research breakthroughs in the field of cannabis are revolutionizing the way we view this plant and its potential benefits. With recent studies showing promising results in treating a variety of medical conditions, including chronic pain, epilepsy, and even cancer, its no wonder that cannabis news is making headlines around the world.

One of the most exciting developments in cannabis research is the discovery of cannabinoids, compounds found in the plant that have been shown to have significant therapeutic effects. These cannabinoids interact with receptors in the bodys endocannabinoid system, which plays a crucial role in regulating functions such as pain perception, mood, and appetite. By targeting these receptors, researchers believe that cannabis could offer new treatment options for patients suffering from a wide range of ailments.

In addition to cannabinoids, researchers are also exploring other chemical compounds found in cannabis that may have medicinal properties. For example, terpenes are aromatic molecules that give cannabis its distinct smell and flavor, but they may also play a role in enhancing the plants therapeutic effects. Studies have shown that certain terpenes can help reduce inflammation, relieve pain, and even combat anxiety and depression.

As more research is conducted on cannabis and its potential medical applications, we can expect to see even more breakthroughs in the coming years. These discoveries could lead to new treatments for conditions that have been difficult to manage with traditional medications, offering hope to patients who have been searching for relief.

Overall, the future of medical cannabis research looks bright, with promising findings paving the way for innovative treatments and improved patient outcomes. By staying informed on the latest developments in this field, we can all contribute to advancing our understanding of cannabis and unlocking its full potential as a medicine.

Cannabis has been a hot topic in the medical field for its potential role in pain management for chronic conditions.. Chronic pain affects millions of people worldwide, and finding effective treatments can be challenging.

Posted by on 2025-04-10

In todays fast-paced world, it seems like technology is constantly evolving and changing.. This is especially true in the cannabis industry, where new advancements and innovations are being made all the time.

Posted by on 2025-04-10

Medical marijuana research and studies have been gaining more attention and significance in recent years as the debate surrounding the use of cannabis for medicinal purposes continues to evolve.. With more states legalizing medical marijuana and with an increasing number of patients seeking alternative treatments for various health conditions, it has become imperative to conduct thorough research and studies to fully understand the potential benefits and risks of using marijuana as a form of treatment. One of the key areas of focus in medical marijuana research is its potential to alleviate symptoms associated with chronic pain, cancer, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and other debilitating conditions.

Posted by on 2025-04-10

In the ever-evolving world of cannabis news, staying up-to-date on industry trends and analysis is crucial for businesses and consumers alike. As legalization efforts continue to spread across the globe, its important to understand how these changes are shaping the cannabis market.

One major trend that has been gaining traction is the increasing acceptance and normalization of cannabis use. With more states and countries legalizing both medical and recreational use, there is a growing demand for high-quality products and services within the industry. This shift in public perception has led to a surge in investment opportunities and job creation within the cannabis sector.

In addition to changing attitudes towards cannabis, technological advancements are also playing a key role in shaping the industry. From innovative cultivation techniques to cutting-edge extraction methods, companies are constantly finding new ways to improve product quality and efficiency. This focus on research and development is driving rapid growth in the market as consumers seek out safe and effective cannabis products.

Furthermore, regulatory changes continue to impact the cannabis industry as lawmakers work to establish clear guidelines for cultivation, distribution, and consumption. Understanding these regulations is essential for businesses looking to operate legally and ethically within the industry. By staying informed on legislative developments, companies can position themselves for long-term success in an increasingly competitive market.

Overall, keeping abreast of industry trends and analysis is vital for navigating the complex landscape of cannabis news. Whether youre a business owner, investor, or consumer, having a solid understanding of these factors can help you make informed decisions that drive growth and innovation within the booming cannabis industry.

International cannabis news covers a wide range of topics related to the rapidly growing and evolving cannabis industry. From updates on legalization efforts in different countries to changes in regulations and laws governing the use of cannabis, this type of news is essential for anyone interested in staying informed about the latest developments in the world of marijuana.

One of the most significant aspects of international cannabis news is the shifting attitudes towards medical and recreational use of marijuana around the world. With more and more countries legalizing or decriminalizing cannabis, there is a growing need for accurate and up-to-date information on how these changes will impact consumers, businesses, and policymakers.

In addition to legislative updates, international cannabis news also covers breakthroughs in research and technology related to cannabis cultivation, extraction methods, and product development. As scientists continue to explore the potential health benefits of cannabinoids like CBD and THC, new discoveries are constantly being made that could revolutionize the way we think about medical marijuana.

Overall, international cannabis news plays a crucial role in shaping public opinion and influencing decision-makers at all levels of government. By providing unbiased reporting on all aspects of the cannabis industry, this type of news helps to educate the public and promote a more informed debate on the complex issues surrounding marijuana legalization.

| Cannabis

Temporal range: Early Miocene – Present

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Common hemp | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis L. |

| Species[1] | |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

Cannabis (/ˈkænÉ™bɪs/ ⓘ)[2] is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae that is widely accepted as being indigenous to and originating from the continent of Asia.[3][4][5] However, the number of species is disputed, with as many as three species being recognized: Cannabis sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis. Alternatively, C. ruderalis may be included within C. sativa, or all three may be treated as subspecies of C. sativa,[1][6][7][8] or C. sativa may be accepted as a single undivided species.[9]

The plant is also known as hemp, although this term is usually used to refer only to varieties cultivated for non-drug use. Hemp has long been used for fibre, seeds and their oils, leaves for use as vegetables, and juice. Industrial hemp textile products are made from cannabis plants selected to produce an abundance of fibre.

Cannabis also has a long history of being used for medicinal purposes, and as a recreational drug known by several slang terms, such as marijuana, pot or weed. Various cannabis strains have been bred, often selectively to produce high or low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a cannabinoid and the plant's principal psychoactive constituent. Compounds such as hashish and hash oil are extracted from the plant.[10] More recently, there has been interest in other cannabinoids like cannabidiol (CBD), cannabigerol (CBG), and cannabinol (CBN).

Cannabis is a Scythian word.[11][12][13] The ancient Greeks learned of the use of cannabis by observing Scythian funerals, during which cannabis was consumed.[12] In Akkadian, cannabis was known as qunubu (ðŽ¯ðŽ«ðŽ ðŽð‚).[12] The word was adopted in to the Hebrew language as qaneh bosem (×§Ö¸× Ö¶×” בֹּשׂ×).[12]

Cannabis is an annual, dioecious, flowering herb. The leaves are palmately compound or digitate, with serrate leaflets.[14] The first pair of leaves usually have a single leaflet, the number gradually increasing up to a maximum of about thirteen leaflets per leaf (usually seven or nine), depending on variety and growing conditions. At the top of a flowering plant, this number again diminishes to a single leaflet per leaf. The lower leaf pairs usually occur in an opposite leaf arrangement and the upper leaf pairs in an alternate arrangement on the main stem of a mature plant.

The leaves have a peculiar and diagnostic venation pattern (which varies slightly among varieties) that allows for easy identification of Cannabis leaves from unrelated species with similar leaves. As is common in serrated leaves, each serration has a central vein extending to its tip, but in Cannabis this originates from lower down the central vein of the leaflet, typically opposite to the position of the second notch down. This means that on its way from the midrib of the leaflet to the point of the serration, the vein serving the tip of the serration passes close by the intervening notch. Sometimes the vein will pass tangentially to the notch, but often will pass by at a small distance; when the latter happens a spur vein (or occasionally two) branches off and joins the leaf margin at the deepest point of the notch. Tiny samples of Cannabis also can be identified with precision by microscopic examination of leaf cells and similar features, requiring special equipment and expertise.[15]

All known strains of Cannabis are wind-pollinated[16] and the fruit is an achene.[17] Most strains of Cannabis are short day plants,[16] with the possible exception of C. sativa subsp. sativa var. spontanea (= C. ruderalis), which is commonly described as "auto-flowering" and may be day-neutral.

Cannabis is predominantly dioecious,[16][18] having imperfect flowers, with staminate "male" and pistillate "female" flowers occurring on separate plants.[19] "At a very early period the Chinese recognized the Cannabis plant as dioecious",[20] and the (c. 3rd century BCE) Erya dictionary defined xi 枲 "male Cannabis" and fu 莩 (or ju 苴) "female Cannabis".[21] Male flowers are normally borne on loose panicles, and female flowers are borne on racemes.[22]

Many monoecious varieties have also been described,[23] in which individual plants bear both male and female flowers.[24] (Although monoecious plants are often referred to as "hermaphrodites", true hermaphrodites – which are less common in Cannabis – bear staminate and pistillate structures together on individual flowers, whereas monoecious plants bear male and female flowers at different locations on the same plant.) Subdioecy (the occurrence of monoecious individuals and dioecious individuals within the same population) is widespread.[25][26][27] Many populations have been described as sexually labile.[28][29][30]

As a result of intensive selection in cultivation, Cannabis exhibits many sexual phenotypes that can be described in terms of the ratio of female to male flowers occurring in the individual, or typical in the cultivar.[31] Dioecious varieties are preferred for drug production, where the fruits (produced by female flowers) are used. Dioecious varieties are also preferred for textile fiber production, whereas monoecious varieties are preferred for pulp and paper production. It has been suggested that the presence of monoecy can be used to differentiate licit crops of monoecious hemp from illicit drug crops,[25] but sativa strains often produce monoecious individuals, which is possibly as a result of inbreeding.

Cannabis has been described as having one of the most complicated mechanisms of sex determination among the dioecious plants.[31] Many models have been proposed to explain sex determination in Cannabis.

Based on studies of sex reversal in hemp, it was first reported by K. Hirata in 1924 that an XY sex-determination system is present.[29] At the time, the XY system was the only known system of sex determination. The X:A system was first described in Drosophila spp in 1925.[32] Soon thereafter, Schaffner disputed Hirata's interpretation,[33] and published results from his own studies of sex reversal in hemp, concluding that an X:A system was in use and that furthermore sex was strongly influenced by environmental conditions.[30]

Since then, many different types of sex determination systems have been discovered, particularly in plants.[18] Dioecy is relatively uncommon in the plant kingdom, and a very low percentage of dioecious plant species have been determined to use the XY system. In most cases where the XY system is found it is believed to have evolved recently and independently.[34]

Since the 1920s, a number of sex determination models have been proposed for Cannabis. Ainsworth describes sex determination in the genus as using "an X/autosome dosage type".[18]

The question of whether heteromorphic sex chromosomes are indeed present is most conveniently answered if such chromosomes were clearly visible in a karyotype. Cannabis was one of the first plant species to be karyotyped; however, this was in a period when karyotype preparation was primitive by modern standards. Heteromorphic sex chromosomes were reported to occur in staminate individuals of dioecious "Kentucky" hemp, but were not found in pistillate individuals of the same variety. Dioecious "Kentucky" hemp was assumed to use an XY mechanism. Heterosomes were not observed in analyzed individuals of monoecious "Kentucky" hemp, nor in an unidentified German cultivar. These varieties were assumed to have sex chromosome composition XX.[35] According to other researchers, no modern karyotype of Cannabis had been published as of 1996.[36] Proponents of the XY system state that Y chromosome is slightly larger than the X, but difficult to differentiate cytologically.[37]

More recently, Sakamoto and various co-authors[38][39] have used random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) to isolate several genetic marker sequences that they name Male-Associated DNA in Cannabis (MADC), and which they interpret as indirect evidence of a male chromosome. Several other research groups have reported identification of male-associated markers using RAPD and amplified fragment length polymorphism.[40][28][41] Ainsworth commented on these findings, stating,

It is not surprising that male-associated markers are relatively abundant. In dioecious plants where sex chromosomes have not been identified, markers for maleness indicate either the presence of sex chromosomes which have not been distinguished by cytological methods or that the marker is tightly linked to a gene involved in sex determination.[18]

Environmental sex determination is known to occur in a variety of species.[42] Many researchers have suggested that sex in Cannabis is determined or strongly influenced by environmental factors.[30] Ainsworth reviews that treatment with auxin and ethylene have feminizing effects, and that treatment with cytokinins and gibberellins have masculinizing effects.[18] It has been reported that sex can be reversed in Cannabis using chemical treatment.[43] A polymerase chain reaction-based method for the detection of female-associated DNA polymorphisms by genotyping has been developed.[44]

Cannabis plants produce a large number of chemicals as part of their defense against herbivory. One group of these is called cannabinoids, which induce mental and physical effects when consumed.

Cannabinoids, terpenes, terpenoids, and other compounds are secreted by glandular trichomes that occur most abundantly on the floral calyxes and bracts of female plants.[46]

Cannabis, like many organisms, is diploid, having a chromosome complement of 2n=20, although polyploid individuals have been artificially produced.[47] The first genome sequence of Cannabis, which is estimated to be 820 Mb in size, was published in 2011 by a team of Canadian scientists.[48]

The genus Cannabis was formerly placed in the nettle family (Urticaceae) or mulberry family (Moraceae), and later, along with the genus Humulus (hops), in a separate family, the hemp family (Cannabaceae sensu stricto).[49] Recent phylogenetic studies based on cpDNA restriction site analysis and gene sequencing strongly suggest that the Cannabaceae sensu stricto arose from within the former family Celtidaceae, and that the two families should be merged to form a single monophyletic family, the Cannabaceae sensu lato.[50][51]

Various types of Cannabis have been described, and variously classified as species, subspecies, or varieties:[52]

Cannabis plants produce a unique family of terpeno-phenolic compounds called cannabinoids, some of which produce the "high" which may be experienced from consuming marijuana. There are 483 identifiable chemical constituents known to exist in the cannabis plant,[53] and at least 85 different cannabinoids have been isolated from the plant.[54] The two cannabinoids usually produced in greatest abundance are cannabidiol (CBD) and/or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but only THC is psychoactive.[55] Since the early 1970s, Cannabis plants have been categorized by their chemical phenotype or "chemotype", based on the overall amount of THC produced, and on the ratio of THC to CBD.[56] Although overall cannabinoid production is influenced by environmental factors, the THC/CBD ratio is genetically determined and remains fixed throughout the life of a plant.[40] Non-drug plants produce relatively low levels of THC and high levels of CBD, while drug plants produce high levels of THC and low levels of CBD. When plants of these two chemotypes cross-pollinate, the plants in the first filial (F1) generation have an intermediate chemotype and produce intermediate amounts of CBD and THC. Female plants of this chemotype may produce enough THC to be utilized for drug production.[56][57]

Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of Cannabis constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a species.[58] One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[59] Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.[59] Physiological barriers to reproduction are not known to occur within Cannabis, and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.[47] However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled Cannabis gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.[60] It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and genetic divergence occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.[61][62][63]

The genus Cannabis was first classified using the "modern" system of taxonomic nomenclature by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, who devised the system still in use for the naming of species.[64] He considered the genus to be monotypic, having just a single species that he named Cannabis sativa L.[a 1] Linnaeus was familiar with European hemp, which was widely cultivated at the time. This classification was supported by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (in 1807), Lindley (in 1838) and De Candollee (in 1867). These first classification attempts resulted in a four group division:[65]

In 1785, evolutionary biologist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck published a description of a second species of Cannabis, which he named Cannabis indica Lam.[66] Lamarck based his description of the newly named species on morphological aspects (trichomes, leaf shape) and geographic localization of plant specimens collected in India. He described C. indica as having poorer fiber quality than C. sativa, but greater utility as an inebriant. Also, C. indica was considered smaller, by Lamarck. Also, woodier stems, alternate ramifications of the branches, narrow leaflets, and a villous calyx in the female flowers were characteristics noted by the botanist.[65]

In 1843, William O’Shaughnessy, used "Indian hemp (C. indica)" in a work title. The author claimed that this choice wasn't based on a clear distinction between C. sativa and C. indica, but may have been influenced by the choice to use the term "Indian hemp" (linked to the plant's history in India), hence naming the species as indica.[65]

Additional Cannabis species were proposed in the 19th century, including strains from China and Vietnam (Indo-China) assigned the names Cannabis chinensis Delile, and Cannabis gigantea Delile ex Vilmorin.[67] However, many taxonomists found these putative species difficult to distinguish. In the early 20th century, the single-species concept (monotypic classification) was still widely accepted, except in the Soviet Union, where Cannabis continued to be the subject of active taxonomic study. The name Cannabis indica was listed in various Pharmacopoeias, and was widely used to designate Cannabis suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.[68]

In 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that ruderal Cannabis in central Russia is either a variety of C. sativa or a separate species, and proposed C. sativa L. var. ruderalis Janisch, and Cannabis ruderalis Janisch, as alternative names.[52] In 1929, renowned plant explorer Nikolai Vavilov assigned wild or feral populations of Cannabis in Afghanistan to C. indica Lam. var. kafiristanica Vav., and ruderal populations in Europe to C. sativa L. var. spontanea Vav.[57][67] Vavilov, in 1931, proposed a three species system, independently reinforced by Schultes et al (1975)[69] and Emboden (1974):[70] C. sativa, C. indica and C. ruderalis.[65]

In 1940, Russian botanists Serebriakova and Sizov proposed a complex poly-species classification in which they also recognized C. sativa and C. indica as separate species. Within C. sativa they recognized two subspecies: C. sativa L. subsp. culta Serebr. (consisting of cultivated plants), and C. sativa L. subsp. spontanea (Vav.) Serebr. (consisting of wild or feral plants). Serebriakova and Sizov split the two C. sativa subspecies into 13 varieties, including four distinct groups within subspecies culta. However, they did not divide C. indica into subspecies or varieties.[52][71][72] Zhukovski, in 1950, also proposed a two-species system, but with C. sativa L. and C. ruderalis.[73]

In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of Cannabis took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting Cannabis in the United States and Canada specifically named products of C. sativa as prohibited materials. Enterprising attorneys for the defense in a few drug busts argued that the seized Cannabis material may not have been C. sativa, and was therefore not prohibited by law. Attorneys on both sides recruited botanists to provide expert testimony. Among those testifying for the prosecution was Dr. Ernest Small, while Dr. Richard E. Schultes and others testified for the defense. The botanists engaged in heated debate (outside of court), and both camps impugned the other's integrity.[61][62] The defense attorneys were not often successful in winning their case, because the intent of the law was clear.[74]

In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small[75] and American taxonomist Arthur Cronquist published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of Cannabis with two subspecies (hemp or drug; based on THC and CBD levels) and two varieties in each (domesticated or wild). The framework is thus:

This classification was based on several factors including interfertility, chromosome uniformity, chemotype, and numerical analysis of phenotypic characters.[56][67][76]

Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist Richard E. Schultes and coworkers also conducted taxonomic studies of Cannabis in the 1970s, and concluded that stable morphological differences exist that support recognition of at least three species, C. sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis.[77][78][79][80] For Schultes, this was a reversal of his previous interpretation that Cannabis is monotypic, with only a single species.[81] According to Schultes' and Anderson's descriptions, C. sativa is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, C. indica is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and C. ruderalis is short, branchless, and grows wild in Central Asia. This taxonomic interpretation was embraced by Cannabis aficionados who commonly distinguish narrow-leafed "sativa" strains from wide-leafed "indica" strains.[82] McPartland's review finds the Schultes taxonomy inconsistent with prior work (protologs) and partly responsible for the popular usage.[83]

Molecular analytical techniques developed in the late 20th century are being applied to questions of taxonomic classification. This has resulted in many reclassifications based on evolutionary systematics. Several studies of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and other types of genetic markers have been conducted on drug and fiber strains of Cannabis, primarily for plant breeding and forensic purposes.[84][85][28][86][87] Dutch Cannabis researcher E.P.M. de Meijer and coworkers described some of their RAPD studies as showing an "extremely high" degree of genetic polymorphism between and within populations, suggesting a high degree of potential variation for selection, even in heavily selected hemp cultivars.[40] They also commented that these analyses confirm the continuity of the Cannabis gene pool throughout the studied accessions, and provide further confirmation that the genus consists of a single species, although theirs was not a systematic study per se.

An investigation of genetic, morphological, and chemotaxonomic variation among 157 Cannabis accessions of known geographic origin, including fiber, drug, and feral populations showed cannabinoid variation in Cannabis germplasm. The patterns of cannabinoid variation support recognition of C. sativa and C. indica as separate species, but not C. ruderalis. C. sativa contains fiber and seed landraces, and feral populations, derived from Europe, Central Asia, and Turkey. Narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug accessions, southern and eastern Asian hemp accessions, and feral Himalayan populations were assigned to C. indica.[57] In 2005, a genetic analysis of the same set of accessions led to a three-species classification, recognizing C. sativa, C. indica, and (tentatively) C. ruderalis.[60] Another paper in the series on chemotaxonomic variation in the terpenoid content of the essential oil of Cannabis revealed that several wide-leaflet drug strains in the collection had relatively high levels of certain sesquiterpene alcohols, including guaiol and isomers of eudesmol, that set them apart from the other putative taxa.[88]

A 2020 analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms reports five clusters of cannabis, roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".[89]

Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the University of British Columbia found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).[90] Legalization of cannabis in Canada (as of 17 October 2018[update]) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.[91]

The scientific debate regarding taxonomy has had little effect on the terminology in widespread use among cultivators and users of drug-type Cannabis. Cannabis aficionados recognize three distinct types based on such factors as morphology, native range, aroma, and subjective psychoactive characteristics. "Sativa" is the most widespread variety, which is usually tall, laxly branched, and found in warm lowland regions. "Indica" designates shorter, bushier plants adapted to cooler climates and highland environments. "Ruderalis" is the informal name for the short plants that grow wild in Europe and Central Asia.[83]

Mapping the morphological concepts to scientific names in the Small 1976 framework, "Sativa" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. indica var. indica, "Indica" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. i. kafiristanica (also known as afghanica), and "Ruderalis", being lower in THC, is the one that can fall into C. sativa subsp. sativa. The three names fit in Schultes's framework better, if one overlooks its inconsistencies with prior work.[83] Definitions of the three terms using factors other than morphology produces different, often conflicting results.

Breeders, seed companies, and cultivators of drug type Cannabis often describe the ancestry or gross phenotypic characteristics of cultivars by categorizing them as "pure indica", "mostly indica", "indica/sativa", "mostly sativa", or "pure sativa". These categories are highly arbitrary, however: one "AK-47" hybrid strain has received both "Best Sativa" and "Best Indica" awards.[83]

Cannabis likely split from its closest relative, Humulus (hops), during the mid Oligocene, around 27.8 million years ago according to molecular clock estimates. The centre of origin of Cannabis is likely in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. The pollen of Humulus and Cannabis are very similar and difficult to distinguish. The oldest pollen thought to be from Cannabis is from Ningxia, China, on the boundary between the Tibetan Plateau and the Loess Plateau, dating to the early Miocene, around 19.6 million years ago. Cannabis was widely distributed over Asia by the Late Pleistocene. The oldest known Cannabis in South Asia dates to around 32,000 years ago.[92]

Cannabis is used for a wide variety of purposes.

According to genetic and archaeological evidence, cannabis was first domesticated about 12,000 years ago in East Asia during the early Neolithic period.[5] The use of cannabis as a mind-altering drug has been documented by archaeological finds in prehistoric societies in Eurasia and Africa.[93] The oldest written record of cannabis usage is the Greek historian Herodotus's reference to the central Eurasian Scythians taking cannabis steam baths.[94] His (c. 440 BCE) Histories records, "The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed [presumably, flowers], and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Greek vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy."[95] Classical Greeks and Romans also used cannabis.

In China, the psychoactive properties of cannabis are described in the Shennong Bencaojing (3rd century AD).[96] Cannabis smoke was inhaled by Daoists, who burned it in incense burners.[96]

In the Middle East, use spread throughout the Islamic empire to North Africa. In 1545, cannabis spread to the western hemisphere where Spaniards imported it to Chile for its use as fiber. In North America, cannabis, in the form of hemp, was grown for use in rope, cloth and paper.[97][98][99][100]

Cannabinol (CBN) was the first compound to be isolated from cannabis extract in the late 1800s. Its structure and chemical synthesis were achieved by 1940, followed by some of the first preclinical research studies to determine the effects of individual cannabis-derived compounds in vivo.[101]

Globally, in 2013, 60,400 kilograms of cannabis were produced legally.[102]

Cannabis is a popular recreational drug around the world, only behind alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. In the U.S. alone, it is believed that over 100 million Americans have tried cannabis, with 25 million Americans having used it within the past year.[when?][104] As a drug it usually comes in the form of dried marijuana, hashish, or various extracts collectively known as hashish oil.[10]

Normal cognition is restored after approximately three hours for larger doses via a smoking pipe, bong or vaporizer.[105] However, if a large amount is taken orally the effects may last much longer. After 24 hours to a few days, minuscule psychoactive effects may be felt, depending on dosage, frequency and tolerance to the drug.

Cannabidiol (CBD), which has no intoxicating effects by itself[55] (although sometimes showing a small stimulant effect, similar to caffeine),[106] is thought to attenuate (i.e., reduce)[107] the anxiety-inducing effects of high doses of THC, particularly if administered orally prior to THC exposure.[108]

According to Delphic analysis by British researchers in 2007, cannabis has a lower risk factor for dependence compared to both nicotine and alcohol.[109] However, everyday use of cannabis may be correlated with psychological withdrawal symptoms, such as irritability or insomnia,[105] and susceptibility to a panic attack may increase as levels of THC metabolites rise.[110][111] Cannabis withdrawal symptoms are typically mild and are not life-threatening.[112] Risk of adverse outcomes from cannabis use may be reduced by implementation of evidence-based education and intervention tools communicated to the public with practical regulation measures.[113]

In 2014 there were an estimated 182.5 million cannabis users worldwide (3.8% of the global population aged 15–64).[114] This percentage did not change significantly between 1998 and 2014.[114]

Medical cannabis (or medical marijuana) refers to the use of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids, in an effort to treat disease or improve symptoms. Cannabis is used to reduce nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy, to improve appetite in people with HIV/AIDS, and to treat chronic pain and muscle spasms.[115][116] Cannabinoids are under preliminary research for their potential to affect stroke.[117] Evidence is lacking for depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychosis.[118] Two extracts of cannabis – dronabinol and nabilone – are approved by the FDA as medications in pill form for treating the side effects of chemotherapy and AIDS.[119]

Short-term use increases both minor and major adverse effects.[116] Common side effects include dizziness, feeling tired, vomiting, and hallucinations.[116] Long-term effects of cannabis are not clear.[120] Concerns including memory and cognition problems, risk of addiction, schizophrenia in young people, and the risk of children taking it by accident.[115]

The term hemp is used to name the durable soft fiber from the Cannabis plant stem (stalk). Cannabis sativa cultivars are used for fibers due to their long stems; Sativa varieties may grow more than six metres tall. However, hemp can refer to any industrial or foodstuff product that is not intended for use as a drug. Many countries regulate limits for psychoactive compound (THC) concentrations in products labeled as hemp.

Cannabis for industrial uses is valuable in tens of thousands of commercial products, especially as fibre[121] ranging from paper, cordage, construction material and textiles in general, to clothing. Hemp is stronger and longer-lasting than cotton. It also is a useful source of foodstuffs (hemp milk, hemp seed, hemp oil) and biofuels. Hemp has been used by many civilizations, from China to Europe (and later North America) during the last 12,000 years.[121][122] In modern times novel applications and improvements have been explored with modest commercial success.[123][124]

In the US, "industrial hemp" is classified by the federal government as cannabis containing no more than 0.3% THC by dry weight. This classification was established in the 2018 Farm Bill and was refined to include hemp-sourced extracts, cannabinoids, and derivatives in the definition of hemp.[125]

The Cannabis plant has a history of medicinal use dating back thousands of years across many cultures.[126] The Yanghai Tombs, a vast ancient cemetery (54 000 m2) situated in the Turfan district of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwest China, have revealed the 2700-year-old grave of a shaman. He is thought to have belonged to the Jushi culture recorded in the area centuries later in the Hanshu, Chap 96B.[127] Near the head and foot of the shaman was a large leather basket and wooden bowl filled with 789g of cannabis, superbly preserved by climatic and burial conditions. An international team demonstrated that this material contained THC. The cannabis was presumably employed by this culture as a medicinal or psychoactive agent, or an aid to divination. This is the oldest documentation of cannabis as a pharmacologically active agent.[128] The earliest evidence of cannabis smoking has been found in the 2,500-year-old tombs of Jirzankal Cemetery in the Pamir Mountains in Western China, where cannabis residue were found in burners with charred pebbles possibly used during funeral rituals.[129][130]

Settlements which date from c. 2200–1700 BCE in the Bactria and Margiana contained elaborate ritual structures with rooms containing everything needed for making drinks containing extracts from poppy (opium), hemp (cannabis), and ephedra (which contains ephedrine).[131]: 262  Although there is no evidence of ephedra being used by steppe tribes, they engaged in cultic use of hemp. Cultic use ranged from Romania to the Yenisei River and had begun by 3rd millennium BC Smoking hemp has been found at Pazyryk.[131]: 306

Cannabis is first referred to in Hindu Vedas between 2000 and 1400 BCE, in the Atharvaveda. By the 10th century CE, it has been suggested that it was referred to by some in India as "food of the gods".[132] Cannabis use eventually became a ritual part of the Hindu festival of Holi. One of the earliest to use this plant in medical purposes was Korakkar, one of the 18 Siddhas.[133][134][self-published source?] The plant is called Korakkar Mooli in the Tamil language, meaning Korakkar's herb.[135][136]

In Buddhism, cannabis is generally regarded as an intoxicant and may be a hindrance to development of meditation and clear awareness. In ancient Germanic culture, Cannabis was associated with the Norse love goddess, Freya.[137][138] An anointing oil mentioned in Exodus is, by some translators, said to contain Cannabis.[139]

In modern times, the Rastafari movement has embraced Cannabis as a sacrament.[140] Elders of the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church, a religious movement founded in the U.S. in 1975 with no ties to either Ethiopia or the Coptic Church, consider Cannabis to be the Eucharist, claiming it as an oral tradition from Ethiopia dating back to the time of Christ.[141] Like the Rastafari, some modern Gnostic Christian sects have asserted that Cannabis is the Tree of Life.[142][143] Other organized religions founded in the 20th century that treat Cannabis as a sacrament are the THC Ministry,[144] Cantheism,[145] the Cannabis Assembly[146] and the Church of Cognizance.

Since the 13th century CE, cannabis has been used among Sufis[147][148] – the mystical interpretation of Islam that exerts strong influence over local Muslim practices in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Turkey, and Pakistan. Cannabis preparations are frequently used at Sufi festivals in those countries.[147] Pakistan's Shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sindh province is particularly renowned for the widespread use of cannabis at the shrine's celebrations, especially its annual Urs festival and Thursday evening dhamaal sessions – or meditative dancing sessions.[149][150]

Cannabis is called kaneh bosem in Hebrew, which is now recognized as the Scythian word that Herodotus wrote as kánnabis (or cannabis).

Cannabis is a Scythian word (Benet 1975).

cite book: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)cite book: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)cite book: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)During the festival the air is heavy with drumbeats, chanting and cannabis smoke.

News is information about current events. This may be provided through many different media: word of mouth, printing, postal systems, broadcasting, electronic communication, or through the testimony of observers and witnesses to events. News is sometimes called "hard news" to differentiate it from soft media.

Subject matters for news reports include war, government, politics, education, health, economy, business, fashion, sport, entertainment, and the environment, as well as quirky or unusual events. Government proclamations, concerning royal ceremonies, laws, taxes, public health, and criminals, have been dubbed news since ancient times. Technological and social developments, often driven by government communication and espionage networks, have increased the speed with which news can spread, as well as influenced its content.

Throughout history, people have transported new information through oral means. Having developed in China over centuries, newspapers became established in Europe during the early modern period. In the 20th century, radio and television became an important means of transmitting news. Whilst in the 21st century, the internet has also begun to play a similar role.

The English word "news" developed in the 14th century as a special use of the plural form of "new". In Middle English, the equivalent word was newes, like the French nouvelles. Similar developments are found in the Slavic languages – namely cognates from Serbo-Croatian novost (from nov, "new"), Czech and Slovak noviny (from nový, "new"), the Polish nowiny (pronounced noviney), the Bulgarian novini and Russian novosti – and likewise in the Celtic languages: the Welsh newyddion (from newydd) and the Cornish nowodhow (from nowydh).[1][2]

Jessica Garretson Finch is credited with coining the phrase "current events" while teaching at Barnard College in the 1890s.[3]

As its name implies, "news" typically connotes the presentation of new information.[4][5] The newness of news gives it an uncertain quality which distinguishes it from the more careful investigations of history or other scholarly disciplines.[5][6][7] Whereas historians tend to view events as causally related manifestations of underlying processes, news stories tend to describe events in isolation, and to exclude discussion of the relationships between them.[8] News conspicuously describes the world in the present or immediate past, even when the most important aspects of a news story have occurred long in the past—or are expected to occur in the future. To make the news, an ongoing process must have some "peg", an event in time that anchors it to the present moment.[8][9] Relatedly, news often addresses aspects of reality which seem unusual, deviant, or out of the ordinary.[10] Hence the famous dictum that "Dog Bites Man" is not news, but "Man Bites Dog" is.[11]

Another corollary of the newness of news is that, as new technology enables new media to disseminate news more quickly, 'slower' forms of communication may move away from 'news' towards 'analysis'.[12]

According to some theories, "news" is whatever the news industry sells.[13] Journalism, broadly understood along the same lines, is the act or occupation of collecting and providing news.[14][15] From a commercial perspective, news is simply one input, along with paper (or an electronic server) necessary to prepare a final product for distribution.[16] A news agency supplies this resource "wholesale" and publishers enhance it for retail.[17][18]

Most purveyors of news value impartiality, neutrality, and objectivity, despite the inherent difficulty of reporting without political bias.[19] Perception of these values has changed greatly over time as sensationalized 'tabloid journalism' has risen in popularity. Michael Schudson has argued that before the era of World War I and the concomitant rise of propaganda, journalists were not aware of the concept of bias in reporting, let alone actively correcting for it.[20] News is also sometimes said to portray the truth, but this relationship is elusive and qualified.[21]

Paradoxically, another property commonly attributed to news is sensationalism, the disproportionate focus on, and exaggeration of, emotive stories for public consumption.[22][23] This news is also not unrelated to gossip, the human practice of sharing information about other humans of mutual interest.[24] A common sensational topic is violence; hence another news dictum, "if it bleeds, it leads".[25]

Newsworthiness is defined as a subject having sufficient relevance to the public or a special audience to warrant press attention or coverage.[26]

News values seem to be common across cultures. People seem to be interested in news to the extent which it has a big impact, describes conflicts, happens nearby, involves well-known people, and deviates from the norms of everyday happenings.[27] War is a common news topic, partly because it involves unknown events that could pose personal danger.[28]

Evidence suggests that cultures around the world have found a place for people to share stories about interesting new information. Among Zulus, Mongolians, Polynesians, and American Southerners, anthropologists have documented the practice of questioning travelers for news as a matter of priority.[29] Sufficiently important news would be repeated quickly and often, and could spread by word of mouth over a large geographic area.[30] Even as printing presses came into use in Europe, news for the general public often travelled orally via monks, travelers, town criers, etc.[31]

The news is also transmitted in public gathering places, such as the Greek forum and the Roman baths. Starting in England, coffeehouses served as important sites for the spread of news, even after telecommunications became widely available. The history of the coffee houses is traced from Arab countries, which was introduced in England in the 16th century.[32] In the Muslim world, people have gathered and exchanged news at mosques and other social places. Travelers on pilgrimages to Mecca traditionally stay at caravanserais, roadside inns, along the way, and these places have naturally served as hubs for gaining news of the world.[33] In late medieval Britain, reports ("tidings") of major events were a topic of great public interest, as chronicled in Chaucer's 1380 The House of Fame and other works.[34]

Before the invention of newspapers in the early 17th century, official government bulletins and edicts were circulated at times in some centralized empires.[35] The first documented use of an organized courier service for the diffusion of written documents is in Egypt, where Pharaohs used couriers for the diffusion of their decrees in the territory of the State (2400 BC).[36] Julius Caesar regularly publicized his heroic deeds in Gaul, and upon becoming dictator of Rome began publishing government announcements called Acta Diurna. These were carved in metal or stone and posted in public places.[37][38] In medieval England, parliamentary declarations were delivered to sheriffs for public display and reading at the market.[39]

Specially sanctioned messengers have been recognized in Vietnamese culture, among the Khasi people in India, and in the Fox and Winnebago cultures of the American midwest. The Zulu Kingdom used runners to quickly disseminate news. In West Africa, news can be spread by griots. In most cases, the official spreaders of news have been closely aligned with holders of political power.[40]

Town criers were a common means of conveying information to citydwellers. In thirteenth-century Florence, criers known as banditori arrived in the market regularly, to announce political news, to convoke public meetings, and to call the populace to arms. In 1307 and 1322–1325, laws were established governing their appointment, conduct, and salary. These laws stipulated how many times a banditoro was to repeat a proclamation (forty) and where in the city they were to read them.[41] Different declarations sometimes came with additional protocols; announcements regarding the plague were also to be read at the city gates.[42] These proclamations all used a standard format, beginning with an exordium—"The worshipful and most esteemed gentlemen of the Eight of Ward and Security of the city of Florence make it known, notify, and expressly command, to whosoever, of whatever status, rank, quality and condition"—and continuing with a statement (narratio), a request made upon the listeners (petitio), and the penalty to be exacted from those who would not comply (peroratio).[43] In addition to major declarations, bandi (announcements) might concern petty crimes, requests for information, and notices about missing slaves.[44] Niccolò Machiavelli was captured by the Medicis in 1513, following a bando calling for his immediate surrender.[45] Some town criers could be paid to include advertising along with news.[46]

Under the Ottoman Empire, official messages were regularly distributed at mosques, by traveling holy men, and by secular criers. These criers were sent to read official announcements in marketplaces, highways, and other well-traveled places, sometimes issuing commands and penalties for disobedience.[47]

The spread of news has always been linked to the communications networks in place to disseminate it. Thus, political, religious, and commercial interests have historically controlled, expanded, and monitored communications channels by which news could spread. Postal services have long been closely entwined with the maintenance of political power in a large area.[48][49]

One of the imperial communication channels, called the "Royal Road" traversed the Assyrian Empire and served as a key source of its power.[50] The Roman Empire maintained a vast network of roads, known as cursus publicus, for similar purposes.[51]

Visible chains of long-distance signaling, known as optical telegraphy, have also been used throughout history to convey limited types of information. These can have ranged from smoke and fire signals to advanced systems using semaphore codes and telescopes.[52][53] The latter form of optical telegraph came into use in Japan, Britain, France, and Germany from the 1790s through the 1850s.[54][55]

The world's first written news may have originated in eighth century BCE China, where reports gathered by officials were eventually compiled as the Spring and Autumn Annals. The annals, whose compilation is attributed to Confucius, were available to a sizeable reading public and dealt with common news themes—though they straddle the line between news and history.[56] The Han dynasty is credited with developing one of the most effective imperial surveillance and communications networks in the ancient world.[57] Government-produced news sheets, called tipao, circulated among court officials during the late Han dynasty (second and third centuries AD). Between 713 and 734, the Kaiyuan Za Bao ("Bulletin of the Court") of the Chinese Tang dynasty published government news; it was handwritten on silk and read by government officials.[58] The court created a Bureau of Official Reports (Jin Zhouyuan) to centralize news distribution for the court.[59] Newsletters called ch'ao pao continued to be produced and gained wider public circulation in the following centuries.[60] In 1582 there was the first reference to privately published newssheets in Beijing, during the late Ming dynasty.[61][62]

Japan had effective communications and postal delivery networks at several points in its history, first in 646 with the Taika Reform and again during the Kamakura period from 1183 to 1333. The system depended on hikyaku, runners, and regularly spaced relay stations. By this method, news could travel between Kyoto and Kamakura in 5–7 days. Special horse-mounted messengers could move information at the speed of 170 kilometers per day.[55][63] The Japanese shogunates were less tolerant than the Chinese government of news circulation.[58] The postal system established during the Edo period was even more effective, with average speeds of 125–150 km/day and express speed of 200 km/day. This system was initially used only by the government, taking private communications only at exorbitant prices. Private services emerged and in 1668 established their own nakama (guild). They became even faster, and created an effective optical telegraphy system using flags by day and lanterns and mirrors by night.[55]

In Europe, during the Middle Ages, elites relied on runners to transmit news over long distances. At 33 kilometres per day, a runner would take two months to bring a message across the Hanseatic League from Bruges to Riga.[64][65] In the early modern period, increased cross-border interaction created a rising need for information which was met by concise handwritten newssheets. The driving force of this new development was the commercial advantage provided by up-to-date news.[7][66]

In 1556, the government of Venice first published the monthly Notizie scritte, which cost one gazetta.[67] These avvisi were handwritten newsletters and used to convey political, military, and economic news quickly and efficiently to Italian cities (1500–1700)—sharing some characteristics of newspapers though usually not considered true newspapers.[68] Avvisi were sold by subscription under the auspices of military, religious, and banking authorities. Sponsorship flavored the contents of each series, which were circulated under many different names. Subscribers included clerics, diplomatic staff, and noble families. By the last quarter of the seventeenth century, long passages from avvisi were finding their way into published monthlies such as the Mercure de France and, in northern Italy, Pallade veneta.[69][70][71]

Postal services enabled merchants and monarchs to stay abreast of important information. For the Holy Roman Empire, Emperor Maximillian I in 1490 authorized two brothers from the Italian Tasso family, Francesco and Janetto, to create a network of courier stations linked by riders. They began with a communications line between Innsbruck and Mechelen and grew from there.[72] In 1505 this network expanded to Spain, new governed by Maximilian's son Philip. These riders could travel 180 kilometers in a day.[73] This system became the Imperial Reichspost, administered by Tasso descendants (subsequently known as Thurn-und-Taxis), who in 1587 received exclusive operating rights from the Emperor.[72] The French postal service and English postal service also began at this time, but did not become comprehensive until the early 1600s.[72][74][75] In 1620, the English system linked with Thurn-und-Taxis.[53]

These connections underpinned an extensive system of news circulation, with handwritten items bearing dates and places of origin. Centred in Germany, the network took in news from Russia, the Balkans, Italy, Britain, France, and the Netherlands.[76] The German lawyer Christoph von Scheurl and the Fugger house of Augsburg were prominent hubs in this network.[77] Letters describing historically significant events could gain wide circulation as news reports. Indeed, personal correspondence sometimes acted only as a convenient channel through which news could flow across a larger network.[78] A common type of business communication was a simple listing of current prices, the circulation of which quickened the flow of international trade.[79][80] Businesspeople also wanted to know about events related to shipping, the affairs of other businesses, and political developments.[79] Even after the advent of international newspapers, business owners still valued correspondence highly as a source of reliable news that would affect their enterprise.[81] Handwritten newsletters, which could be produced quickly for a limited clientele, also continued into the 1600s.[77]

The spread of paper and the printing press from China to Europe preceded a major advance in the transmission of news.[82] With the spread of printing presses and the creation of new markets in the 1500s, news underwent a shift from factual and precise economic reporting, to a more emotive and freewheeling format. (Private newsletters containing important intelligence therefore remained in use by people who needed to know.)[83] The first newspapers emerged in Germany in the early 1600s.[84] Relation aller Fürnemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien, from 1605, is recognized as the world's first formalized 'newspaper';[85] while not a 'newspaper' in the modern sense, the Ancient Roman Acta Diurna served a similar purpose circa 131 BC.

The new format, which mashed together numerous unrelated and perhaps dubious reports from far-flung locations, created a radically new and jarring experience for its readers.[86] A variety of styles emerged, from single-story tales, to compilations, overviews, and personal and impersonal types of news analysis.[87]

News for public consumption was at first tightly controlled by governments. By 1530, England had created a licensing system for the press and banned "seditious opinions".[88] Under the Licensing Act, publication was restricted to approved presses—as exemplified by The London Gazette, which prominently bore the words: "Published By Authority".[89] Parliament allowed the Licensing Act to lapse in 1695, beginning a new era marked by Whig and Tory newspapers.[90] (During this era, the Stamp Act limited newspaper distribution simply by making them expensive to sell and buy.) In France, censorship was even more constant.[91] Consequently, many Europeans read newspapers originating from beyond their national borders—especially from the Dutch Republic, where publishers could evade state censorship.[92]

The new United States saw a newspaper boom beginning with the Revolutionary era, accelerated by spirited debates over the establishment of a new government, spurred on by subsidies contained in the 1792 Postal Service Act, and continuing into the 1800s.[93][94] American newspapers got many of their stories by copying reports from each other. Thus by offering free postage to newspapers wishing to exchange copies, the Postal Service Act subsidized a rapidly growing news network through which different stories could percolate.[95] Newspapers thrived during the colonization of the West, fueled by high literacy and a newspaper-loving culture.[96] By 1880, San Francisco rivaled New York in number of different newspapers and in printed newspaper copies per capita.[97] Boosters of new towns felt that newspapers covering local events brought legitimacy, recognition, and community.[98] The 1830s American, wrote Alexis de Tocqueville, was "a very civilized man prepared for a time to face life in the forest, plunging into the wilderness of the New World with his Bible, ax, and newspapers."[99] In France, the Revolution brought forth an abundance of newspapers and a new climate of press freedom, followed by a return to repression under Napoleon.[100] In 1792 the Revolutionaries set up a news ministry called the Bureau d'Esprit.[101]

Some newspapers published in the 1800s and after retained the commercial orientation characteristic of the private newsletters of the Renaissance. Economically oriented newspapers published new types of data enabled the advent of statistics, especially economic statistics which could inform sophisticated investment decisions.[102] These newspapers, too, became available for larger sections of society, not just elites, keen on investing some of their savings in the stock markets. Yet, as in the case other newspapers, the incorporation of advertising into the newspaper led to justified reservations about accepting newspaper information at face value.[103] Economic newspapers also became promoters of economic ideologies, such as Keynesianism in the mid-1900s.[104]

Newspapers came to sub-Saharan Africa via colonization. The first English-language newspaper in the area was The Royal Gazette and Sierra Leone Advertiser, established in 1801, and followed by The Royal Gold Coast Gazette and Commercial Intelligencer in 1822 and the Liberia Herald in 1826.[105] A number of nineteenth-century African newspapers were established by missionaries.[106] These newspapers by and large promoted the colonial governments and served the interests of European settlers by relaying news from Europe.[106] The first newspaper published in a native African language was the Muigwithania, published in Kikuyu by the Kenyan Central Association.[106] Muigwithania and other newspapers published by indigenous Africans took strong opposition stances, agitating strongly for African independence.[107] Newspapers were censored heavily during the colonial period—as well as after formal independence. Some liberalization and diversification took place in the 1990s.[108]

Newspapers were slow to spread to the Arab world, which had a stronger tradition of oral communication, and mistrust of the European approach to news reporting. By the end of the eighteenth century, the Ottoman Empire's leaders in Istanbul monitored the European press, but its contents were not disseminated for mass consumption.[109] Some of the first written news in modern North Africa arose in Egypt under Muhammad Ali, who developed the local paper industry and initiated the limited circulation of news bulletins called jurnals.[110] Beginning in the 1850s and 1860s, the private press began to develop in the multi-religious country of Lebanon.[111]

The development of the electrical telegraph, which often travelled along railroad lines, enabled news to travel faster, over longer distances.[112] (Days before Morse's Baltimore–Washington line transmitted the famous question, "What hath God wrought?", it transmitted the news that Henry Clay and Theodore Frelinghuysen had been chosen by the Whig nominating party.)[37] Telegraph networks enabled a new centralization of the news, in the hands of wire services concentrated in major cities. The modern form of these originated with Charles-Louis Havas, who founded Bureau Havas (later Agence France-Presse) in Paris. Havas began in 1832, using the French government's optical telegraph network. In 1840 he began using pigeons for communications to Paris, London, and Brussels. Havas began to use the electric telegraph when it became available.[113]

One of Havas's proteges, Bernhard Wolff, founded Wolffs Telegraphisches Bureau in Berlin in 1849.[114] Another Havas disciple, Paul Reuter, began collecting news from Germany and France in 1849, and in 1851 immigrated to London, where he established the Reuters news agency—specializing in news from the continent.[115] In 1863, William Saunders and Edward Spender formed the Central Press agency, later called the Press Association, to handle domestic news.[116] Just before insulated telegraph line crossed the English Channel in 1851, Reuter won the right to transmit stock exchange prices between Paris and London.[117] He maneuvered Reuters into a dominant global position with the motto "Follow the Cable", setting up news outposts across the British Empire in Alexandria (1865), Bombay (1866), Melbourne (1874), Sydney (1874), and Cape Town (1876).[117][118] In the United States, the Associated Press became a news powerhouse, gaining a lead position through an exclusive arrangement with the Western Union company.[119]

The telegraph ushered in a new global communications regime, accompanied by a restructuring of the national postal systems, and closely followed by the advent of telephone lines. With the value of international news at a premium, governments, businesses, and news agencies moved aggressively to reduce transmission times. In 1865, Reuters had the scoop on the Lincoln assassination, reporting the news in England twelve days after the event took place.[120] In 1866, an undersea telegraph cable successfully connected Ireland to Newfoundland (and thus the Western Union network) cutting trans-Atlantic transmission time from days to hours.[121][122][123] The transatlantic cable allowed fast exchange of information about the London and New York stock exchanges, as well as the New York, Chicago, and Liverpool commodity exchanges—for the price of $5–10, in gold, per word.[124] Transmitting On 11 May 1857, a young British telegraph operator in Delhi signaled home to alert the authorities of the Indian Rebellion of 1857. The rebels proceeded to disrupt the British telegraph network, which was rebuilt with more redundancies.[125] In 1902–1903, Britain and the U.S. completed the circumtelegraphy of the planet with transpacific cables from Canada to Fiji and New Zealand (British Empire), and from the US to Hawaii and the occupied Philippines.[126] U.S. reassertions of the Monroe Doctrine notwithstanding, Latin America was a battleground of competing telegraphic interests until World War I, after which U.S. interests finally did consolidate their power in the hemisphere.[127]

By the turn of the century (i.e., c. 1900), Wolff, Havas, and Reuters formed a news cartel, dividing up the global market into three sections, in which each had more-or-less exclusive distribution rights and relationships with national agencies.[128] Each agency's area corresponded roughly to the colonial sphere of its mother country.[129] Reuters and the Australian national news service had an agreement to exchange news only with each other.[130] Due to the high cost of maintaining infrastructure, political goodwill, and global reach, newcomers found it virtually impossible to challenge the big three European agencies or the American Associated Press.[131] In 1890 Reuters (in partnership with the Press Association, England's major news agency for domestic stories) expanded into "soft" news stories for public consumption, about topics such as sports and "human interest".[132] In 1904, the big three wire services opened relations with Vestnik, the news agency of Czarist Russia, to their group, though they maintained their own reporters in Moscow.[133] During and after the Russian Revolution, the outside agencies maintained a working relationship with the Petrograd Telegraph Agency, renamed the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) and eventually the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS).[134]

The Chinese Communist Party created its news agency, the Red China News Agency, in 1931; its primary responsibilities were the Red China newspaper and the internal Reference News. In 1937, the Party renamed it Xinhua News Agency, which became the official news agency of the People's Republic of China in 1949.[135]

These agencies touted their ability to distill events into "minute globules of news", 20–30 word summaries which conveyed the essence of new developments.[134] Unlike newspapers, and contrary to the sentiments of some of their reporters, the agencies sought to keep their reports simple and factual.[136] The wire services brought forth the "inverted pyramid" model of news copy, in which key facts appear at the start of the text, and more and more details are included as it goes along.[121] The sparse telegraphic writing style spilled over into newspapers, which often reprinted stories from the wire with little embellishment.[18][137] In a 20 September 1918 Pravda editorial, Lenin instructed the Soviet press to cut back on their political rambling and produce many short anticapitalist news items in "telegraph style".[138]

As in previous eras, the news agencies provided special services to political and business clients, and these services constituted a significant portion of their operations and income. The wire services maintained close relationships with their respective national governments, which provided both press releases and payments.[139] The acceleration and centralization of economic news facilitated regional economic integration and economic globalization. "It was the decrease in information costs and the increasing communication speed that stood at the roots of increased market integration, rather than falling transport costs by itself. In order to send goods to another area, merchants needed to know first whether in fact to send off the goods and to what place. Information costs and speed were essential for these decisions."[140]

The British Broadcasting Company began transmitting radio news from London in 1922, dependent entirely, by law, on the British news agencies.[141] BBC radio marketed itself as a news by and for social elites, and hired only broadcasters who spoke with upper-class accents.[142] The BBC gained importance in the May 1926 general strike, during which newspapers were closed and the radio served as the only source of news for an uncertain public. (To the displeasure of many listeners, the BBC took an unambiguously pro-government stance against the strikers).[141][143]

In the US, RCA's Radio Group established its radio network, NBC, in 1926. The Paley family founded CBS soon after. These two networks, which supplied news broadcasts to subsidiaries and affiliates, dominated the airwaves throughout the period of radio's hegemony as a news source.[144] Radio broadcasters in the United States negotiated a similar arrangement with the press in 1933, when they agreed to use only news from the Press–Radio Bureau and eschew advertising; this agreement soon collapsed and radio stations began reporting their own news (with advertising).[145] As in Britain, American news radio avoided "controversial" topics as per norms established by the National Association of Broadcasters.[146] By 1939, 58% of Americans surveyed by Fortune considered radio news more accurate than newspapers, and 70% chose radio as their main news source.[146] Radio expanded rapidly across the continent, from 30 stations in 1920 to a thousand in the 1930s. This operation was financed mostly with advertising and public relations money.[147]

The Soviet Union began a major international broadcasting operation in 1929, with stations in German, English and French. The Nazi Party made use of the radio in its rise to power in Germany, with much of its propaganda focused on attacking the Soviet Bolsheviks. The British and Italian foreign radio services competed for influence in North Africa. All four of these broadcast services grew increasingly vitriolic as the European nations prepared for war.[148]

The war provided an opportunity to expand radio and take advantage of its new potential. The BBC reported on Allied invasion of Normandy on 8:00 a.m. of the morning it took place, and including a clip from German radio coverage of the same event. Listeners followed along with developments throughout the day.[149] The U.S. set up its Office of War Information which by 1942 sent programming across South America, the Middle East, and East Asia.[150] Radio Luxembourg, a centrally located high-power station on the continent, was seized by Germany, and then by the United States—which created fake news programs appearing as though they were created by Germany.[151] Targeting American troops in the Pacific, the Japanese government broadcast the "Zero Hour" program, which included news from the U.S. to make the soldiers homesick.[152] But by the end of the war, Britain had the largest radio network in the world, broadcasting internationally in 43 different languages.[153] Its scope would eventually be surpassed (by 1955) by the worldwide Voice of America programs, produced by the United States Information Agency.[154]

In Britain and the United States, television news watching rose dramatically in the 1950s and by the 1960s supplanted radio as the public's primary source of news.[155] In the U.S., television was run by the same networks which owned radio: CBS, NBC, and an NBC spin-off called ABC.[156] Edward R. Murrow, who first entered the public ear as a war reporter in London, made the big leap to television to become an iconic newsman on CBS (and later the director of the United States Information Agency).[157]

Ted Turner's creation of the Cable News Network (CNN) in 1980 inaugurated a new era of 24-hour satellite news broadcasting. In 1991, the BBC introduced a competitor, BBC World Service Television. Rupert Murdoch's Australian News Corporation entered the picture with Fox News Channel in the US, Sky News in Britain, and STAR TV in Asia.[158] Combining this new apparatus with the use of embedded reporters, the United States waged the 1991–1992 Gulf War with the assistance of nonstop media coverage.[159] CNN's specialty is the crisis, to which the network is prepared to shift its total attention if so chosen.[160] CNN news was transmitted via Intelsat communications satellites.[161] CNN, said an executive, would bring a "town crier to the global village".[162]

In 1996, the Qatar-owned broadcaster Al Jazeera emerged as a powerful alternative to the Western media, capitalizing in part on anger in the Arab & Muslim world regarding biased coverage of the Gulf War. Al Jazeera hired many news workers conveniently laid off by BBC Arabic Television, which closed in April 1996. It used Arabsat to broadcast.[158]

The early internet, known as ARPANET, was controlled by the U.S. Department of Defense and used mostly by academics. It became available to a wider public with the release of the Netscape browser in 1994.[163] At first, news websites were mostly archives of print publications.[164] An early online newspaper was the Electronic Telegraph, published by The Daily Telegraph.[165][166] A 1994 earthquake in California was one of the first big stories to be reported online in real time.[167] The new availability of web browsing made news sites accessible to more people.[167] On the day of the Oklahoma City bombing in April 1995, people flocked to newsgroups and chatrooms to discuss the situation and share information. The Oklahoma City Daily posted news to its site within hours. Two of the only news sites capable of hosting images, the San Jose Mercury News and Time magazine, posted photographs of the scene.[167]

Quantitatively, the internet has massively expanded the sheer volume of news items available to one person. The speed of news flow to individuals has also reached a new plateau.[168] This insurmountable flow of news can daunt people and cause information overload. Zbigniew Brzezinski called this period the "technetronic era", in which "global reality increasingly absorbs the individual, involves him, and even occasionally overwhelms him."[169]

In cases of government crackdowns or revolutions, the Internet has often become a major communication channel for news propagation; while shutting down a newspaper, radio or television station is (relatively) simple, mobile devices such as smartphones and netbooks are much harder to detect and confiscate. The propagation of internet-capable mobile devices has also given rise to the citizen journalist, who provide an additional perspective on unfolding events.

News can travel through different communication media.[17] In modern times, printed news had to be phoned into a newsroom or brought there by a reporter, where it was typed and either transmitted over wire services or edited and manually set in type along with other news stories for a specific edition. Today, the term "breaking news" has become trite as commercial broadcasting United States cable news services that are available 24 hours a day use live communications satellite technology to bring current events into consumers' homes as the event occurs. Events that used to take hours or days to become common knowledge in towns or in nations are fed instantaneously to consumers via radio, television, mobile phone, and the internet.

Speed of news transmission varies wildly on the basis of where and how one lives.[170]