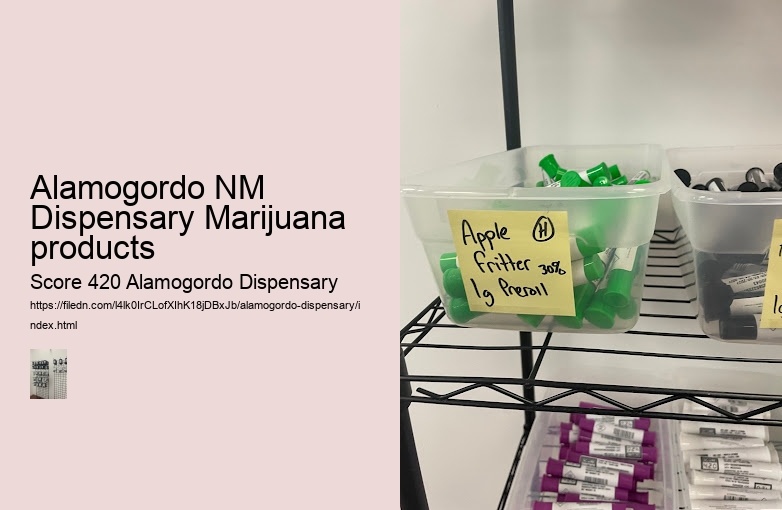

When it comes to popular marijuana products at Alamogordo NM Dispensary, there are a few standout options that customers just can't get enough of. From top-shelf flower strains to potent concentrates and delicious edibles, there is something for everyone at this local cannabis shop.

One of the most sought-after products is high-quality flower, with a variety of different strains available to suit every preference. Whether you're looking for a relaxing indica to unwind after a long day or a stimulating sativa to boost your creativity, the selection at Alamogordo NM Dispensary has you covered.

For those who prefer a more potent experience, concentrates like shatter, wax, and live resin are also popular choices. These highly concentrated forms of cannabis offer a powerful high in small doses, making them perfect for experienced users looking for an intense experience.

And let's not forget about edibles – from gummies and chocolates to infused beverages and baked goods, there are plenty of tasty options available at Alamogordo NM Dispensary. These discreet and delicious treats are perfect for those who want to enjoy the effects of marijuana without having to smoke or vape.

No matter what your preferred method of consumption may be, Alamogordo NM Dispensary has something for everyone. With knowledgeable staff members ready to help you find the perfect product for your needs, this dispensary is truly a one-stop shop for all your marijuana needs.

Quality control measures are essential for ensuring that marijuana products meet high standards of safety, potency, and consistency. In Alamogordo NM Dispensary, these measures are implemented to guarantee that customers receive only the best quality products.

One of the main aspects of quality control measures is testing. Marijuana products go through rigorous testing procedures to determine their cannabinoid levels, terpene profiles, and presence of any contaminants such as pesticides or heavy metals. This ensures that customers can trust the potency and purity of the products they are purchasing.

Another important aspect of quality control measures is proper labeling. Each product is labeled with detailed information about its ingredients, dosage, and recommended usage. This helps customers make informed decisions about which products are right for them and ensures transparency in the buying process.

Additionally, Alamogordo NM Dispensary takes great care in storing and handling marijuana products properly to prevent degradation or contamination. By following strict protocols for storage and handling, they can guarantee that customers receive fresh and potent products every time.

In conclusion, quality control measures play a vital role in ensuring that marijuana products sold at Alamogordo NM Dispensary meet high standards of safety and efficacy. By implementing thorough testing procedures, accurate labeling practices, and proper storage protocols, they demonstrate their commitment to providing customers with top-quality products they can trust.

In Alamogordo, NM, the legal age to purchase cannabis is 21 years old.. This means that individuals must be at least 21 years of age in order to legally purchase cannabis products from licensed dispensaries in the city. This age restriction is in place to help ensure that cannabis products are only being consumed by adults who are of legal age to make informed decisions about their use.

Posted by on 2025-04-02

When it comes to finding the best cannabis products in Alamogordo, NM, there are a few key things to keep in mind.. With the growing popularity of cannabis for both medical and recreational use, the market is flooded with options - making it crucial to do your research and find the products that best meet your needs. One of the first things to consider when looking for cannabis products is the reputation of the dispensary or retailer.

Posted by on 2025-04-02

Have you been searching for a place where you can truly relax and unwind?. Look no further than our dispensary in Alamogordo NM.

Posted by on 2025-04-02

When it comes to purchasing marijuana products at an Alamogordo NM dispensary, pricing and specials play a significant role in the decision-making process. Customers are always on the lookout for deals and discounts that can help them save money while still getting high-quality products.

At our dispensary in Alamogordo NM, we understand the importance of offering competitive pricing and attractive specials to our customers. We regularly update our pricing to ensure that it remains affordable and accessible to everyone. Whether you're looking for flower, edibles, concentrates, or topicals, you can trust that our prices are fair and reasonable.

In addition to our everyday low prices, we also run specials and promotions on a regular basis. These specials may include discounts on specific products, buy-one-get-one deals, or even freebies with purchase. By taking advantage of these specials, customers can stretch their dollars further and try out new products without breaking the bank.

Our goal is to make shopping for marijuana products a pleasant experience for our customers. That's why we keep our pricing transparent and straightforward, so there are no surprises at checkout. Whether you're a seasoned cannabis enthusiast or a first-time buyer, you can count on us to provide you with great value for your money.

So next time you're in Alamogordo NM and looking for high-quality marijuana products at affordable prices, stop by our dispensary and check out our pricing and specials. We're here to help you find exactly what you need while saving you money along the way.

When it comes to finding the best marijuana products in Alamogordo, NM, customer reviews and testimonials can be extremely helpful. Hearing from real people who have tried the products can give you a better idea of what to expect and help you make an informed decision.

Whether you're looking for top-quality flower, potent concentrates, or delicious edibles, reading reviews from other customers can point you in the right direction. From personal experiences with different strains to recommendations on dosage and consumption methods, these reviews offer valuable insights that can enhance your shopping experience.

Many customers also share their thoughts on the service they received at dispensaries in Alamogordo. Friendly staff, a welcoming atmosphere, and a wide selection of products are all factors that contribute to a positive experience for customers. By reading these testimonials, you can ensure that you choose a dispensary that meets your needs and provides excellent customer service.

Overall, customer reviews and testimonials play a crucial role in helping individuals navigate the world of marijuana products in Alamogordo. By listening to the experiences of others, you can make more informed decisions about which products to try and where to shop. So next time you're looking for the best marijuana products in town, be sure to check out what other customers have to say!

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012)

|

A dispensary is an office in a school, hospital, industrial plant, or other organization that dispenses medications, medical supplies, and in some cases even medical and dental treatment. In a traditional dispensary set-up, a pharmacist dispenses medication per the prescription or order form. The English term originated from the medieval Latin noun dispensaria and is cognate with the Latin verb dispensare, 'to distribute'.[1]

The term also refers to legal cannabis dispensaries.

The term also has Victorian antiquity, in 1862 the term dispensary was used in the folk song the Blaydon Races.[2] The folk song differentiated the term dispensary from a Doctors surgery and an Infirmary.[2] The advent of huge industrial plants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as large steel mills, created a demand for in-house first responder services, including firefighting, emergency medical services, and even primary care that were closer to the point of need, under closer company control, and in many cases better capitalized than any services that the surrounding town could provide. In such contexts, company doctors and nurses were regularly on duty or on call.

Electronic dispensaries are designed to ensure efficient and consistent dispensing of excipient and active ingredients in a secure data environment with full audit traceability. A standard dispensary system consists of a range of modules such as manual dispensing, supervisory, bulk dispensing, recipe management and interfacing with external systems. Such a system might dispense much more than just medical related products, such as alcohol, tobacco or vitamins and minerals.

In Kenya, a dispensary is a small outpatient health facility, usually managed by a registered nurse. It provides the most basic primary healthcare services to rural communities, e.g. childhood immunization, family planning, wound dressing and management of common ailments like colds, diarrhea and simple malaria. The nurses report to the nursing officer at the health center, where they refer patients with complicated diseases to be managed by clinical officers.

In India, a dispensary refers to a small setup with basic medical facilities where a doctor can provide a primary level of care. It does not have a hospitalization facility and is generally owned by a single doctor. In remote areas of India where hospital facilities are not available, dispensaries will be available.

In Turkey, the term dispensary is almost always used in reference to tuberculosis dispensaries (Turkish: verem savaÅŸ dispanseri) established across the country under a programme to eliminate tuberculosis initiated in 1923,[3] the same year the country was founded. Although more than a hundred such dispensaries continue to operate as of 2023, they have been largely supplanted by hospitals by the end of 20th century with increased access to healthcare.

The term dispensary in the United States was used to refer to government agencies that sell alcoholic beverages, particularly in the state of Idaho and the South Carolina.

In Arizona, British Columbia, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Oregon, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Rhode Island, Ontario, Quebec, and Washington, medical cannabis is sold in specially designated stores called cannabis dispensaries or "compassion clubs".[4] These clubs are for members or patients only, unless legal cannabis has already passed in the state or province in question. In Canada dispensaries are far less abundant than in the USA; most Canadian dispensaries are in British Columbia and Ontario.[5][6]

In 2013 Uruguay became the first country to legalize marijuana cultivation, sale and consumption. The government is building a network of dispensaries that are meant to help to track marijuana sales and consumption. The move was meant to decrease the role of the criminal world in distribution and sales of it.[7]

But them that had their noses broke they cam back ower hyem; Sum went to the Dispensary an' uthers to Doctor Gibbs, An' sum sought out the Infirmary to mend their broken ribs.

| Cannabis

Temporal range: Early Miocene – Present

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Common hemp | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis L. |

| Species[1] | |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

Cannabis (/ˈkænÉ™bɪs/ ⓘ)[2] is a genus of flowering plants in the family Cannabaceae that is widely accepted as being indigenous to and originating from the continent of Asia.[3][4][5] However, the number of species is disputed, with as many as three species being recognized: Cannabis sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis. Alternatively, C. ruderalis may be included within C. sativa, or all three may be treated as subspecies of C. sativa,[1][6][7][8] or C. sativa may be accepted as a single undivided species.[9]

The plant is also known as hemp, although this term is usually used to refer only to varieties cultivated for non-drug use. Hemp has long been used for fibre, seeds and their oils, leaves for use as vegetables, and juice. Industrial hemp textile products are made from cannabis plants selected to produce an abundance of fibre.

Cannabis also has a long history of being used for medicinal purposes, and as a recreational drug known by several slang terms, such as marijuana, pot or weed. Various cannabis strains have been bred, often selectively to produce high or low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a cannabinoid and the plant's principal psychoactive constituent. Compounds such as hashish and hash oil are extracted from the plant.[10] More recently, there has been interest in other cannabinoids like cannabidiol (CBD), cannabigerol (CBG), and cannabinol (CBN).

Cannabis is a Scythian word.[11][12][13] The ancient Greeks learned of the use of cannabis by observing Scythian funerals, during which cannabis was consumed.[12] In Akkadian, cannabis was known as qunubu (ðŽ¯ðŽ«ðŽ ðŽð‚).[12] The word was adopted in to the Hebrew language as qaneh bosem (×§Ö¸× Ö¶×” בֹּשׂ×).[12]

Cannabis is an annual, dioecious, flowering herb. The leaves are palmately compound or digitate, with serrate leaflets.[14] The first pair of leaves usually have a single leaflet, the number gradually increasing up to a maximum of about thirteen leaflets per leaf (usually seven or nine), depending on variety and growing conditions. At the top of a flowering plant, this number again diminishes to a single leaflet per leaf. The lower leaf pairs usually occur in an opposite leaf arrangement and the upper leaf pairs in an alternate arrangement on the main stem of a mature plant.

The leaves have a peculiar and diagnostic venation pattern (which varies slightly among varieties) that allows for easy identification of Cannabis leaves from unrelated species with similar leaves. As is common in serrated leaves, each serration has a central vein extending to its tip, but in Cannabis this originates from lower down the central vein of the leaflet, typically opposite to the position of the second notch down. This means that on its way from the midrib of the leaflet to the point of the serration, the vein serving the tip of the serration passes close by the intervening notch. Sometimes the vein will pass tangentially to the notch, but often will pass by at a small distance; when the latter happens a spur vein (or occasionally two) branches off and joins the leaf margin at the deepest point of the notch. Tiny samples of Cannabis also can be identified with precision by microscopic examination of leaf cells and similar features, requiring special equipment and expertise.[15]

All known strains of Cannabis are wind-pollinated[16] and the fruit is an achene.[17] Most strains of Cannabis are short day plants,[16] with the possible exception of C. sativa subsp. sativa var. spontanea (= C. ruderalis), which is commonly described as "auto-flowering" and may be day-neutral.

Cannabis is predominantly dioecious,[16][18] having imperfect flowers, with staminate "male" and pistillate "female" flowers occurring on separate plants.[19] "At a very early period the Chinese recognized the Cannabis plant as dioecious",[20] and the (c. 3rd century BCE) Erya dictionary defined xi 枲 "male Cannabis" and fu 莩 (or ju 苴) "female Cannabis".[21] Male flowers are normally borne on loose panicles, and female flowers are borne on racemes.[22]

Many monoecious varieties have also been described,[23] in which individual plants bear both male and female flowers.[24] (Although monoecious plants are often referred to as "hermaphrodites", true hermaphrodites – which are less common in Cannabis – bear staminate and pistillate structures together on individual flowers, whereas monoecious plants bear male and female flowers at different locations on the same plant.) Subdioecy (the occurrence of monoecious individuals and dioecious individuals within the same population) is widespread.[25][26][27] Many populations have been described as sexually labile.[28][29][30]

As a result of intensive selection in cultivation, Cannabis exhibits many sexual phenotypes that can be described in terms of the ratio of female to male flowers occurring in the individual, or typical in the cultivar.[31] Dioecious varieties are preferred for drug production, where the fruits (produced by female flowers) are used. Dioecious varieties are also preferred for textile fiber production, whereas monoecious varieties are preferred for pulp and paper production. It has been suggested that the presence of monoecy can be used to differentiate licit crops of monoecious hemp from illicit drug crops,[25] but sativa strains often produce monoecious individuals, which is possibly as a result of inbreeding.

Cannabis has been described as having one of the most complicated mechanisms of sex determination among the dioecious plants.[31] Many models have been proposed to explain sex determination in Cannabis.

Based on studies of sex reversal in hemp, it was first reported by K. Hirata in 1924 that an XY sex-determination system is present.[29] At the time, the XY system was the only known system of sex determination. The X:A system was first described in Drosophila spp in 1925.[32] Soon thereafter, Schaffner disputed Hirata's interpretation,[33] and published results from his own studies of sex reversal in hemp, concluding that an X:A system was in use and that furthermore sex was strongly influenced by environmental conditions.[30]

Since then, many different types of sex determination systems have been discovered, particularly in plants.[18] Dioecy is relatively uncommon in the plant kingdom, and a very low percentage of dioecious plant species have been determined to use the XY system. In most cases where the XY system is found it is believed to have evolved recently and independently.[34]

Since the 1920s, a number of sex determination models have been proposed for Cannabis. Ainsworth describes sex determination in the genus as using "an X/autosome dosage type".[18]

The question of whether heteromorphic sex chromosomes are indeed present is most conveniently answered if such chromosomes were clearly visible in a karyotype. Cannabis was one of the first plant species to be karyotyped; however, this was in a period when karyotype preparation was primitive by modern standards. Heteromorphic sex chromosomes were reported to occur in staminate individuals of dioecious "Kentucky" hemp, but were not found in pistillate individuals of the same variety. Dioecious "Kentucky" hemp was assumed to use an XY mechanism. Heterosomes were not observed in analyzed individuals of monoecious "Kentucky" hemp, nor in an unidentified German cultivar. These varieties were assumed to have sex chromosome composition XX.[35] According to other researchers, no modern karyotype of Cannabis had been published as of 1996.[36] Proponents of the XY system state that Y chromosome is slightly larger than the X, but difficult to differentiate cytologically.[37]

More recently, Sakamoto and various co-authors[38][39] have used random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) to isolate several genetic marker sequences that they name Male-Associated DNA in Cannabis (MADC), and which they interpret as indirect evidence of a male chromosome. Several other research groups have reported identification of male-associated markers using RAPD and amplified fragment length polymorphism.[40][28][41] Ainsworth commented on these findings, stating,

It is not surprising that male-associated markers are relatively abundant. In dioecious plants where sex chromosomes have not been identified, markers for maleness indicate either the presence of sex chromosomes which have not been distinguished by cytological methods or that the marker is tightly linked to a gene involved in sex determination.[18]

Environmental sex determination is known to occur in a variety of species.[42] Many researchers have suggested that sex in Cannabis is determined or strongly influenced by environmental factors.[30] Ainsworth reviews that treatment with auxin and ethylene have feminizing effects, and that treatment with cytokinins and gibberellins have masculinizing effects.[18] It has been reported that sex can be reversed in Cannabis using chemical treatment.[43] A polymerase chain reaction-based method for the detection of female-associated DNA polymorphisms by genotyping has been developed.[44]

Cannabis plants produce a large number of chemicals as part of their defense against herbivory. One group of these is called cannabinoids, which induce mental and physical effects when consumed.

Cannabinoids, terpenes, terpenoids, and other compounds are secreted by glandular trichomes that occur most abundantly on the floral calyxes and bracts of female plants.[46]

Cannabis, like many organisms, is diploid, having a chromosome complement of 2n=20, although polyploid individuals have been artificially produced.[47] The first genome sequence of Cannabis, which is estimated to be 820 Mb in size, was published in 2011 by a team of Canadian scientists.[48]

The genus Cannabis was formerly placed in the nettle family (Urticaceae) or mulberry family (Moraceae), and later, along with the genus Humulus (hops), in a separate family, the hemp family (Cannabaceae sensu stricto).[49] Recent phylogenetic studies based on cpDNA restriction site analysis and gene sequencing strongly suggest that the Cannabaceae sensu stricto arose from within the former family Celtidaceae, and that the two families should be merged to form a single monophyletic family, the Cannabaceae sensu lato.[50][51]

Various types of Cannabis have been described, and variously classified as species, subspecies, or varieties:[52]

Cannabis plants produce a unique family of terpeno-phenolic compounds called cannabinoids, some of which produce the "high" which may be experienced from consuming marijuana. There are 483 identifiable chemical constituents known to exist in the cannabis plant,[53] and at least 85 different cannabinoids have been isolated from the plant.[54] The two cannabinoids usually produced in greatest abundance are cannabidiol (CBD) and/or Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), but only THC is psychoactive.[55] Since the early 1970s, Cannabis plants have been categorized by their chemical phenotype or "chemotype", based on the overall amount of THC produced, and on the ratio of THC to CBD.[56] Although overall cannabinoid production is influenced by environmental factors, the THC/CBD ratio is genetically determined and remains fixed throughout the life of a plant.[40] Non-drug plants produce relatively low levels of THC and high levels of CBD, while drug plants produce high levels of THC and low levels of CBD. When plants of these two chemotypes cross-pollinate, the plants in the first filial (F1) generation have an intermediate chemotype and produce intermediate amounts of CBD and THC. Female plants of this chemotype may produce enough THC to be utilized for drug production.[56][57]

Whether the drug and non-drug, cultivated and wild types of Cannabis constitute a single, highly variable species, or the genus is polytypic with more than one species, has been a subject of debate for well over two centuries. This is a contentious issue because there is no universally accepted definition of a species.[58] One widely applied criterion for species recognition is that species are "groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations which are reproductively isolated from other such groups."[59] Populations that are physiologically capable of interbreeding, but morphologically or genetically divergent and isolated by geography or ecology, are sometimes considered to be separate species.[59] Physiological barriers to reproduction are not known to occur within Cannabis, and plants from widely divergent sources are interfertile.[47] However, physical barriers to gene exchange (such as the Himalayan mountain range) might have enabled Cannabis gene pools to diverge before the onset of human intervention, resulting in speciation.[60] It remains controversial whether sufficient morphological and genetic divergence occurs within the genus as a result of geographical or ecological isolation to justify recognition of more than one species.[61][62][63]

The genus Cannabis was first classified using the "modern" system of taxonomic nomenclature by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, who devised the system still in use for the naming of species.[64] He considered the genus to be monotypic, having just a single species that he named Cannabis sativa L.[a 1] Linnaeus was familiar with European hemp, which was widely cultivated at the time. This classification was supported by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (in 1807), Lindley (in 1838) and De Candollee (in 1867). These first classification attempts resulted in a four group division:[65]

In 1785, evolutionary biologist Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck published a description of a second species of Cannabis, which he named Cannabis indica Lam.[66] Lamarck based his description of the newly named species on morphological aspects (trichomes, leaf shape) and geographic localization of plant specimens collected in India. He described C. indica as having poorer fiber quality than C. sativa, but greater utility as an inebriant. Also, C. indica was considered smaller, by Lamarck. Also, woodier stems, alternate ramifications of the branches, narrow leaflets, and a villous calyx in the female flowers were characteristics noted by the botanist.[65]

In 1843, William O’Shaughnessy, used "Indian hemp (C. indica)" in a work title. The author claimed that this choice wasn't based on a clear distinction between C. sativa and C. indica, but may have been influenced by the choice to use the term "Indian hemp" (linked to the plant's history in India), hence naming the species as indica.[65]

Additional Cannabis species were proposed in the 19th century, including strains from China and Vietnam (Indo-China) assigned the names Cannabis chinensis Delile, and Cannabis gigantea Delile ex Vilmorin.[67] However, many taxonomists found these putative species difficult to distinguish. In the early 20th century, the single-species concept (monotypic classification) was still widely accepted, except in the Soviet Union, where Cannabis continued to be the subject of active taxonomic study. The name Cannabis indica was listed in various Pharmacopoeias, and was widely used to designate Cannabis suitable for the manufacture of medicinal preparations.[68]

In 1924, Russian botanist D.E. Janichevsky concluded that ruderal Cannabis in central Russia is either a variety of C. sativa or a separate species, and proposed C. sativa L. var. ruderalis Janisch, and Cannabis ruderalis Janisch, as alternative names.[52] In 1929, renowned plant explorer Nikolai Vavilov assigned wild or feral populations of Cannabis in Afghanistan to C. indica Lam. var. kafiristanica Vav., and ruderal populations in Europe to C. sativa L. var. spontanea Vav.[57][67] Vavilov, in 1931, proposed a three species system, independently reinforced by Schultes et al (1975)[69] and Emboden (1974):[70] C. sativa, C. indica and C. ruderalis.[65]

In 1940, Russian botanists Serebriakova and Sizov proposed a complex poly-species classification in which they also recognized C. sativa and C. indica as separate species. Within C. sativa they recognized two subspecies: C. sativa L. subsp. culta Serebr. (consisting of cultivated plants), and C. sativa L. subsp. spontanea (Vav.) Serebr. (consisting of wild or feral plants). Serebriakova and Sizov split the two C. sativa subspecies into 13 varieties, including four distinct groups within subspecies culta. However, they did not divide C. indica into subspecies or varieties.[52][71][72] Zhukovski, in 1950, also proposed a two-species system, but with C. sativa L. and C. ruderalis.[73]

In the 1970s, the taxonomic classification of Cannabis took on added significance in North America. Laws prohibiting Cannabis in the United States and Canada specifically named products of C. sativa as prohibited materials. Enterprising attorneys for the defense in a few drug busts argued that the seized Cannabis material may not have been C. sativa, and was therefore not prohibited by law. Attorneys on both sides recruited botanists to provide expert testimony. Among those testifying for the prosecution was Dr. Ernest Small, while Dr. Richard E. Schultes and others testified for the defense. The botanists engaged in heated debate (outside of court), and both camps impugned the other's integrity.[61][62] The defense attorneys were not often successful in winning their case, because the intent of the law was clear.[74]

In 1976, Canadian botanist Ernest Small[75] and American taxonomist Arthur Cronquist published a taxonomic revision that recognizes a single species of Cannabis with two subspecies (hemp or drug; based on THC and CBD levels) and two varieties in each (domesticated or wild). The framework is thus:

This classification was based on several factors including interfertility, chromosome uniformity, chemotype, and numerical analysis of phenotypic characters.[56][67][76]

Professors William Emboden, Loran Anderson, and Harvard botanist Richard E. Schultes and coworkers also conducted taxonomic studies of Cannabis in the 1970s, and concluded that stable morphological differences exist that support recognition of at least three species, C. sativa, C. indica, and C. ruderalis.[77][78][79][80] For Schultes, this was a reversal of his previous interpretation that Cannabis is monotypic, with only a single species.[81] According to Schultes' and Anderson's descriptions, C. sativa is tall and laxly branched with relatively narrow leaflets, C. indica is shorter, conical in shape, and has relatively wide leaflets, and C. ruderalis is short, branchless, and grows wild in Central Asia. This taxonomic interpretation was embraced by Cannabis aficionados who commonly distinguish narrow-leafed "sativa" strains from wide-leafed "indica" strains.[82] McPartland's review finds the Schultes taxonomy inconsistent with prior work (protologs) and partly responsible for the popular usage.[83]

Molecular analytical techniques developed in the late 20th century are being applied to questions of taxonomic classification. This has resulted in many reclassifications based on evolutionary systematics. Several studies of random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and other types of genetic markers have been conducted on drug and fiber strains of Cannabis, primarily for plant breeding and forensic purposes.[84][85][28][86][87] Dutch Cannabis researcher E.P.M. de Meijer and coworkers described some of their RAPD studies as showing an "extremely high" degree of genetic polymorphism between and within populations, suggesting a high degree of potential variation for selection, even in heavily selected hemp cultivars.[40] They also commented that these analyses confirm the continuity of the Cannabis gene pool throughout the studied accessions, and provide further confirmation that the genus consists of a single species, although theirs was not a systematic study per se.

An investigation of genetic, morphological, and chemotaxonomic variation among 157 Cannabis accessions of known geographic origin, including fiber, drug, and feral populations showed cannabinoid variation in Cannabis germplasm. The patterns of cannabinoid variation support recognition of C. sativa and C. indica as separate species, but not C. ruderalis. C. sativa contains fiber and seed landraces, and feral populations, derived from Europe, Central Asia, and Turkey. Narrow-leaflet and wide-leaflet drug accessions, southern and eastern Asian hemp accessions, and feral Himalayan populations were assigned to C. indica.[57] In 2005, a genetic analysis of the same set of accessions led to a three-species classification, recognizing C. sativa, C. indica, and (tentatively) C. ruderalis.[60] Another paper in the series on chemotaxonomic variation in the terpenoid content of the essential oil of Cannabis revealed that several wide-leaflet drug strains in the collection had relatively high levels of certain sesquiterpene alcohols, including guaiol and isomers of eudesmol, that set them apart from the other putative taxa.[88]

A 2020 analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphisms reports five clusters of cannabis, roughly corresponding to hemps (including folk "Ruderalis") folk "Indica" and folk "Sativa".[89]

Despite advanced analytical techniques, much of the cannabis used recreationally is inaccurately classified. One laboratory at the University of British Columbia found that Jamaican Lamb's Bread, claimed to be 100% sativa, was in fact almost 100% indica (the opposite strain).[90] Legalization of cannabis in Canada (as of 17 October 2018[update]) may help spur private-sector research, especially in terms of diversification of strains. It should also improve classification accuracy for cannabis used recreationally. Legalization coupled with Canadian government (Health Canada) oversight of production and labelling will likely result in more—and more accurate—testing to determine exact strains and content. Furthermore, the rise of craft cannabis growers in Canada should ensure quality, experimentation/research, and diversification of strains among private-sector producers.[91]

The scientific debate regarding taxonomy has had little effect on the terminology in widespread use among cultivators and users of drug-type Cannabis. Cannabis aficionados recognize three distinct types based on such factors as morphology, native range, aroma, and subjective psychoactive characteristics. "Sativa" is the most widespread variety, which is usually tall, laxly branched, and found in warm lowland regions. "Indica" designates shorter, bushier plants adapted to cooler climates and highland environments. "Ruderalis" is the informal name for the short plants that grow wild in Europe and Central Asia.[83]

Mapping the morphological concepts to scientific names in the Small 1976 framework, "Sativa" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. indica var. indica, "Indica" generally refers to C. sativa subsp. i. kafiristanica (also known as afghanica), and "Ruderalis", being lower in THC, is the one that can fall into C. sativa subsp. sativa. The three names fit in Schultes's framework better, if one overlooks its inconsistencies with prior work.[83] Definitions of the three terms using factors other than morphology produces different, often conflicting results.

Breeders, seed companies, and cultivators of drug type Cannabis often describe the ancestry or gross phenotypic characteristics of cultivars by categorizing them as "pure indica", "mostly indica", "indica/sativa", "mostly sativa", or "pure sativa". These categories are highly arbitrary, however: one "AK-47" hybrid strain has received both "Best Sativa" and "Best Indica" awards.[83]

Cannabis likely split from its closest relative, Humulus (hops), during the mid Oligocene, around 27.8 million years ago according to molecular clock estimates. The centre of origin of Cannabis is likely in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau. The pollen of Humulus and Cannabis are very similar and difficult to distinguish. The oldest pollen thought to be from Cannabis is from Ningxia, China, on the boundary between the Tibetan Plateau and the Loess Plateau, dating to the early Miocene, around 19.6 million years ago. Cannabis was widely distributed over Asia by the Late Pleistocene. The oldest known Cannabis in South Asia dates to around 32,000 years ago.[92]

Cannabis is used for a wide variety of purposes.

According to genetic and archaeological evidence, cannabis was first domesticated about 12,000 years ago in East Asia during the early Neolithic period.[5] The use of cannabis as a mind-altering drug has been documented by archaeological finds in prehistoric societies in Eurasia and Africa.[93] The oldest written record of cannabis usage is the Greek historian Herodotus's reference to the central Eurasian Scythians taking cannabis steam baths.[94] His (c. 440 BCE) Histories records, "The Scythians, as I said, take some of this hemp-seed [presumably, flowers], and, creeping under the felt coverings, throw it upon the red-hot stones; immediately it smokes, and gives out such a vapour as no Greek vapour-bath can exceed; the Scyths, delighted, shout for joy."[95] Classical Greeks and Romans also used cannabis.

In China, the psychoactive properties of cannabis are described in the Shennong Bencaojing (3rd century AD).[96] Cannabis smoke was inhaled by Daoists, who burned it in incense burners.[96]

In the Middle East, use spread throughout the Islamic empire to North Africa. In 1545, cannabis spread to the western hemisphere where Spaniards imported it to Chile for its use as fiber. In North America, cannabis, in the form of hemp, was grown for use in rope, cloth and paper.[97][98][99][100]

Cannabinol (CBN) was the first compound to be isolated from cannabis extract in the late 1800s. Its structure and chemical synthesis were achieved by 1940, followed by some of the first preclinical research studies to determine the effects of individual cannabis-derived compounds in vivo.[101]

Globally, in 2013, 60,400 kilograms of cannabis were produced legally.[102]

Cannabis is a popular recreational drug around the world, only behind alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco. In the U.S. alone, it is believed that over 100 million Americans have tried cannabis, with 25 million Americans having used it within the past year.[when?][104] As a drug it usually comes in the form of dried marijuana, hashish, or various extracts collectively known as hashish oil.[10]

Normal cognition is restored after approximately three hours for larger doses via a smoking pipe, bong or vaporizer.[105] However, if a large amount is taken orally the effects may last much longer. After 24 hours to a few days, minuscule psychoactive effects may be felt, depending on dosage, frequency and tolerance to the drug.

Cannabidiol (CBD), which has no intoxicating effects by itself[55] (although sometimes showing a small stimulant effect, similar to caffeine),[106] is thought to attenuate (i.e., reduce)[107] the anxiety-inducing effects of high doses of THC, particularly if administered orally prior to THC exposure.[108]

According to Delphic analysis by British researchers in 2007, cannabis has a lower risk factor for dependence compared to both nicotine and alcohol.[109] However, everyday use of cannabis may be correlated with psychological withdrawal symptoms, such as irritability or insomnia,[105] and susceptibility to a panic attack may increase as levels of THC metabolites rise.[110][111] Cannabis withdrawal symptoms are typically mild and are not life-threatening.[112] Risk of adverse outcomes from cannabis use may be reduced by implementation of evidence-based education and intervention tools communicated to the public with practical regulation measures.[113]

In 2014 there were an estimated 182.5 million cannabis users worldwide (3.8% of the global population aged 15–64).[114] This percentage did not change significantly between 1998 and 2014.[114]

Medical cannabis (or medical marijuana) refers to the use of cannabis and its constituent cannabinoids, in an effort to treat disease or improve symptoms. Cannabis is used to reduce nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy, to improve appetite in people with HIV/AIDS, and to treat chronic pain and muscle spasms.[115][116] Cannabinoids are under preliminary research for their potential to affect stroke.[117] Evidence is lacking for depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, Tourette syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychosis.[118] Two extracts of cannabis – dronabinol and nabilone – are approved by the FDA as medications in pill form for treating the side effects of chemotherapy and AIDS.[119]

Short-term use increases both minor and major adverse effects.[116] Common side effects include dizziness, feeling tired, vomiting, and hallucinations.[116] Long-term effects of cannabis are not clear.[120] Concerns including memory and cognition problems, risk of addiction, schizophrenia in young people, and the risk of children taking it by accident.[115]

The term hemp is used to name the durable soft fiber from the Cannabis plant stem (stalk). Cannabis sativa cultivars are used for fibers due to their long stems; Sativa varieties may grow more than six metres tall. However, hemp can refer to any industrial or foodstuff product that is not intended for use as a drug. Many countries regulate limits for psychoactive compound (THC) concentrations in products labeled as hemp.

Cannabis for industrial uses is valuable in tens of thousands of commercial products, especially as fibre[121] ranging from paper, cordage, construction material and textiles in general, to clothing. Hemp is stronger and longer-lasting than cotton. It also is a useful source of foodstuffs (hemp milk, hemp seed, hemp oil) and biofuels. Hemp has been used by many civilizations, from China to Europe (and later North America) during the last 12,000 years.[121][122] In modern times novel applications and improvements have been explored with modest commercial success.[123][124]

In the US, "industrial hemp" is classified by the federal government as cannabis containing no more than 0.3% THC by dry weight. This classification was established in the 2018 Farm Bill and was refined to include hemp-sourced extracts, cannabinoids, and derivatives in the definition of hemp.[125]

The Cannabis plant has a history of medicinal use dating back thousands of years across many cultures.[126] The Yanghai Tombs, a vast ancient cemetery (54 000 m2) situated in the Turfan district of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in northwest China, have revealed the 2700-year-old grave of a shaman. He is thought to have belonged to the Jushi culture recorded in the area centuries later in the Hanshu, Chap 96B.[127] Near the head and foot of the shaman was a large leather basket and wooden bowl filled with 789g of cannabis, superbly preserved by climatic and burial conditions. An international team demonstrated that this material contained THC. The cannabis was presumably employed by this culture as a medicinal or psychoactive agent, or an aid to divination. This is the oldest documentation of cannabis as a pharmacologically active agent.[128] The earliest evidence of cannabis smoking has been found in the 2,500-year-old tombs of Jirzankal Cemetery in the Pamir Mountains in Western China, where cannabis residue were found in burners with charred pebbles possibly used during funeral rituals.[129][130]

Settlements which date from c. 2200–1700 BCE in the Bactria and Margiana contained elaborate ritual structures with rooms containing everything needed for making drinks containing extracts from poppy (opium), hemp (cannabis), and ephedra (which contains ephedrine).[131]: 262  Although there is no evidence of ephedra being used by steppe tribes, they engaged in cultic use of hemp. Cultic use ranged from Romania to the Yenisei River and had begun by 3rd millennium BC Smoking hemp has been found at Pazyryk.[131]: 306

Cannabis is first referred to in Hindu Vedas between 2000 and 1400 BCE, in the Atharvaveda. By the 10th century CE, it has been suggested that it was referred to by some in India as "food of the gods".[132] Cannabis use eventually became a ritual part of the Hindu festival of Holi. One of the earliest to use this plant in medical purposes was Korakkar, one of the 18 Siddhas.[133][134][self-published source?] The plant is called Korakkar Mooli in the Tamil language, meaning Korakkar's herb.[135][136]

In Buddhism, cannabis is generally regarded as an intoxicant and may be a hindrance to development of meditation and clear awareness. In ancient Germanic culture, Cannabis was associated with the Norse love goddess, Freya.[137][138] An anointing oil mentioned in Exodus is, by some translators, said to contain Cannabis.[139]

In modern times, the Rastafari movement has embraced Cannabis as a sacrament.[140] Elders of the Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church, a religious movement founded in the U.S. in 1975 with no ties to either Ethiopia or the Coptic Church, consider Cannabis to be the Eucharist, claiming it as an oral tradition from Ethiopia dating back to the time of Christ.[141] Like the Rastafari, some modern Gnostic Christian sects have asserted that Cannabis is the Tree of Life.[142][143] Other organized religions founded in the 20th century that treat Cannabis as a sacrament are the THC Ministry,[144] Cantheism,[145] the Cannabis Assembly[146] and the Church of Cognizance.

Since the 13th century CE, cannabis has been used among Sufis[147][148] – the mystical interpretation of Islam that exerts strong influence over local Muslim practices in Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Turkey, and Pakistan. Cannabis preparations are frequently used at Sufi festivals in those countries.[147] Pakistan's Shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sindh province is particularly renowned for the widespread use of cannabis at the shrine's celebrations, especially its annual Urs festival and Thursday evening dhamaal sessions – or meditative dancing sessions.[149][150]

Cannabis is called kaneh bosem in Hebrew, which is now recognized as the Scythian word that Herodotus wrote as kánnabis (or cannabis).

Cannabis is a Scythian word (Benet 1975).

cite book: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)cite book: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)cite book: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)During the festival the air is heavy with drumbeats, chanting and cannabis smoke.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2025)

|

|

Alamogordo, New Mexico

|

|

|---|---|

|

Downtown Alamogordo, looking west on 10th Street; Jim Griggs Sports Complex; Shops on New York Avenue; Water Tower looking east on Tenth Street; Kids' Kingdom Park; View of Alamogordo from Thunder Road

|

|

Location in New Mexico

|

|

Coordinates: 32°51′22″N 105°58′28″W / 32.85611°N 105.97444°W[3]CountryUnited StatesStateNew MexicoCountyOtero[1][2]Founded1898Incorporated1912Named afterálamo gordo, Spanish for "fat cottonwood"Government

• TypeCommission–manager • MayorSusan Payne[4] • Mayor Pro TemAl Hernandez[4] • City ManagerMaggie Paluch[5]Area

21.58 sq mi (55.90 km2) • Land21.57 sq mi (55.87 km2) • Water0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2)Elevation

4,330 ft (1,320 m)Population

31,384 • Density1,432.32/sq mi (553.02/km2)Time zoneUTC−7 (Mountain Standard Time Zone) • Summer (DST)UTC−6 (Mountain Daylight Time)ZIP codes[8]

Area code575FIPS code35-01780GNIS feature ID2409672[3]Websiteci

Alamogordo (/ËŒælÉ™məˈɡɔËrdoÊŠ/) is a city in and the county seat of Otero County, New Mexico, United States. A city in the Tularosa Basin of the Chihuahuan Desert, it is bordered on the east by the Sacramento Mountains and to the west by Holloman Air Force Base. The population was 31,384 as of the 2020 census. Alamogordo is widely known for its connection with the 1945 Trinity test, which was the first ever explosion of an atomic bomb.

Humans have lived in the Alamogordo area for at least 11,000 years. The present settlement, established in 1898 to support the construction of the El Paso and Northeastern Railroad, is an early example of a planned community. The city was incorporated in 1912. Tourism became an important economic factor with the creation of White Sands National Monument in 1933, which is still one of the biggest attractions of the city today. During the 1950s and 1960s, Alamogordo was an unofficial center for research on pilot safety and the developing United States' space program.

Alamogordo is a charter city with a council-manager form of government. City government provides a large number of recreational and leisure facilities for its citizens, including a large park in the center of the city, many smaller parks scattered through the city, a golf course, Alameda Park Zoo, a network of walking paths, Alamogordo Public Library, and a senior citizens' center. Gerald Champion Regional Medical Center is a nonprofit shared military/civilian facility that is also the hospital for Holloman Air Force Base.

Tularosa Basin has been inhabited for at least 11,000 years. There are signs of previous inhabitants in the area such as the Clovis culture, the Folsom culture, the peoples of the Archaic period, and the Formative stage.[9] The Mescalero Apache were already living in the Tularosa Basin when the Spanish came in 1534, and Mescalero oral history says they have always lived there.[10] In 1719, the Spanish built a chapel at La Luz (about 5 miles (8.0 km) from the future site of Alamogordo), although La Luz was not settled until about 1860.[11][12]: 167

The city of Alamogordo was founded in June 1898, when the El Paso and Northeastern Railroad, headed by Charles Bishop Eddy, extended the railway to the town.[13]: 4, 6–7  Eddy influenced the design of the community, which included large, wide thoroughfares and tree-lined irrigation canals.[14] Charles Eddy's brother, John Arthur Eddy, named the new city. He created a neologism adapted from the Spanish words for "large/fat cottonwood"[15] after a grove of stout cottonwoods he remembered from the Pecos River area.[13]: x–1  However, the word "Almagordo" was not used in the Spanish language.[16] When Alamogordo was laid out in 1898, the east–west streets were given numerical designations, while north–south streets were named after states. The present-day White Sands Boulevard was then called Pennsylvania Avenue.[12]: 42, 44–45

With the creation of White Sands National Monument in 1934, tourism began.[13]: 53

The Works Progress Administration, a government program created in 1935 in response to the Great Depression, was responsible for the construction of several government buildings in Alamogordo. These include the Otero County Administration Building at 1101 New York Avenue, a Pueblo style building originally constructed as the main U.S. Post Office in 1938. The building is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The main entrance portico features frescoes by Peter Hurd, which were completed in 1942.[17]

In July 1941, the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range was established.[18]

The Post Office moved out in 1961, and the building was used by a succession of Federal agencies and was known as the Federal Building.[citation needed] The last Federal agency to occupy it was the United States Forest Service who used it as the headquarters of the Lincoln National Forest until October 2008, when that agency moved to a newly constructed building.[19][20] In February 2009, ownership of the building was transferred to Otero County government and many government offices were moved from the Courthouse to its new Administration Building .[21][22]

In 1983, Atari, Inc. buried more than 700,000 unsold Atari 2600 video game cartridges in Alamogordo's landfill.[23] Most notably, Atari discarded many copies of the unpopular E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. This event was often believed to be an urban legend, until it was confirmed by Atari and excavations at the landfill.[24]

Alamogordo briefly made international news in late 2001 when Christ Community Church held a public book burning of books in the Harry Potter series, and several other series, on December 30.[25][26][27]

As of 2010, Alamogordo had a total area of 19.3 square miles (50.0 km2), all land.[28] The city is located on the western flank of the Sacramento Mountains and on the eastern edge of the Tularosa Basin. It lies within the Rio Grande rift[29] and in the northernmost part of the Chihuahuan Desert.[30]: 36  Tectonic activity is low in the Tularosa Basin.[31] Plants native to the area are typical of the southern New Mexico foothills and include creosote bush, mesquite, saltbush, cottonwood, desert willow, and many species of cactus and yucca.[32]

The Tularosa Basin is an endorheic, or closed, basin; that is, no water flows out of it.[31][33] Because of this and because of the geology of the region, water in the basin is hard: it has very high total dissolved solids concentrations, in excess of 3,000 mg/L.[31][34] The Brackish Groundwater National Desalination Research Facility, a Bureau of Reclamation laboratory doing research and development on desalination of brackish water, is located in Alamogordo.[35] The gypsum crystals of White Sands National Park are formed in Lake Lucero. Water drains from the mountains carrying dissolved gypsum and collects in Lake Lucero. After the water dries, the winds pick up the gypsum crystals and distribute them over the basin.[30]: 37

Alamogordo has a semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk), bordering a desert climate (BWk), with hot summers and mild winters. Rainfall is low and usually confined to the monsoon from July to September, when half a typical year's rainfall of 10.63 in (270.0 mm) will occur – although December 1991 did see 5.45 in (138.4 mm). The wettest calendar year has been 1941 with 21.87 in (555.5 mm) and the driest 1952 with 4.85 in (123.2 mm), while the wettest month on record has been September 1941 when 6.94 in (176.3 mm) fell. September 1941 also saw the largest daily rainfall at Alamogordo with 2.60 in (66.0 mm) falling on the 22nd of that month.

Temperatures outside of monsoonal storms are very hot during the summer: 89.1 days exceed 90 °F (32.2 °C) and temperatures as high as 110 °F (43.3 °C) occurred on June 22, 1981, and July 8, 1951. During the winter, days are very mild and sunny, but nights are cold, with 32 °F (0 °C) reached on 55.1 mornings during an average winter, although only ten mornings have ever fallen to or below 0 °F (−17.8 °C),[36] with the coldest temperature recorded at Alamogordo being −13 °F (−25.0 °C) during a major cold wave on February 3, 2011. Snow is very rare, with a mean of no more than 4.1 in (10 cm) and a median very close to zero. The most snowfall in one month was 10.0 in (25 cm) in December 1960.

| Climate data for Alamogordo, New Mexico, elevation 4,330 feet (1,320 m) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1913–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 76 (24) |

82 (28) |

90 (32) |

97 (36) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

110 (43) |

108 (42) |

102 (39) |

96 (36) |

88 (31) |

78 (26) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 68.1 (20.1) |

73.3 (22.9) |

81.3 (27.4) |

87.2 (30.7) |

96.2 (35.7) |

103.0 (39.4) |

102.2 (39.0) |

97.6 (36.4) |

94.6 (34.8) |

87.7 (30.9) |

76.9 (24.9) |

68.7 (20.4) |

104.3 (40.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.8 (12.7) |

60.1 (15.6) |

67.6 (19.8) |

75.8 (24.3) |

84.8 (29.3) |

94.0 (34.4) |

92.6 (33.7) |

91.1 (32.8) |

85.5 (29.7) |

75.4 (24.1) |

63.6 (17.6) |

54.1 (12.3) |

75.0 (23.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.0 (6.7) |

48.7 (9.3) |

55.2 (12.9) |

63.1 (17.3) |

71.7 (22.1) |

81.1 (27.3) |

81.2 (27.3) |

79.4 (26.3) |

74.1 (23.4) |

63.3 (17.4) |

52.1 (11.2) |

43.3 (6.3) |

63.1 (17.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 33.2 (0.7) |

37.3 (2.9) |

42.9 (6.1) |

50.5 (10.3) |

58.6 (14.8) |

68.1 (20.1) |

69.8 (21.0) |

67.8 (19.9) |

62.6 (17.0) |

51.3 (10.7) |

40.6 (4.8) |

32.6 (0.3) |

51.3 (10.7) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 19.3 (−7.1) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

33.9 (1.1) |

42.7 (5.9) |

55.1 (12.8) |

61.2 (16.2) |

59.5 (15.3) |

50.4 (10.2) |

34.3 (1.3) |

23.2 (−4.9) |

17.2 (−8.2) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −4 (−20) |

−13 (−25) |

10 (−12) |

20 (−7) |

32 (0) |

41 (5) |

49 (9) |

48 (9) |

33 (1) |

19 (−7) |

0 (−18) |

−1 (−18) |

−13 (−25) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.68 (17) |

0.59 (15) |

0.33 (8.4) |

0.27 (6.9) |

0.46 (12) |

0.56 (14) |

1.62 (41) |

1.96 (50) |

1.49 (38) |

1.01 (26) |

0.56 (14) |

1.10 (28) |

10.63 (270) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.0 (2.5) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.9 (2.3) |

2.4 (6.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 3.8 | 4.3 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 2.8 | 3.4 | 55.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1.3 |

| Source: NOAA[37][38] | |||||||||||||

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 2,363 | — | |

| 1930 | 3,096 | 31.0% | |

| 1940 | 3,950 | 27.6% | |

| 1950 | 6,783 | 71.7% | |

| 1960 | 21,723 | 220.3% | |

| 1970 | 23,035 | 6.0% | |

| 1980 | 24,024 | 4.3% | |

| 1990 | 27,596 | 14.9% | |

| 2000 | 35,582 | 28.9% | |

| 2010 | 30,403 | −14.6% | |

| 2020 | 31,384 | 3.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[39][7] | |||

As of the census of 2020, there were 31,384 people. During the 2000 census, there were 13,704 households, and 9,728 families residing in the city. There were 15,920 housing units. The racial makeup of the city was 70.4% White; 5.6% African American, 1.1% Native American, 1.5% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 12.1% from some other race, and 4.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 32.0% of the population.[40]: 38

There were 13,704 households, out of which 36.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.6% were married couples living together, 11.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.0% were non-families. 25.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.57 and the average family size was 3.07.[40]: 38

In the city the population was spread out, with 28.7% under the age of 18, 9.2% from 18 to 24, 29.7% from 25 to 44, 19.9% from 45 to 64, and 12.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 97.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.1 males.[40]: 39

In 1999, the median income for a household in the city was $30,928, and the median income for a family was $35,673. Males had a median income of $28,163 versus $18,860 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,662. About 13.2% of families and 16.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.9% of those under age 18 and 11.8% of those age 65 or over.[41]

Alamogordo's and Otero County's July 1, 2008, population were estimated at 35,757 and 62,776 respectively by the United States Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program.[42]

Previously Alamogordo had a German community due to the presence of the German Air Force at Holloman Air Force Base; in 1992 that air force made Holloman its main pilot training center in the United States.[43] Holloman was chosen due to its weather conditions.[44] There was a subdivision called "Little Germany" with houses that had German-style electrical outlets. The Deutsche Schule Alamogordo educated German children, as did the local schools. Additionally area supermarkets had German cuisine.[45]

By 1999, there were about 1,110 German dependents and 900 German military personnel in Alamogordo.[46] By 2003 there were about 2,000 Germans in Alamogordo. That year there were tensions between Americans and Germans since Germany chose not to join the U.S. in the Iraq War.[44]

In 2019, the German military withdrew from the base.[47]

Until the German Air Force left, Oktoberfest was celebrated annually in late September, hosted by the German Air Force at Holloman Air Force Base. The public was invited, and shuttle buses ran between Alamogordo and the base.[48]

Alamogordo is the economic center of Otero County,[49] with nearly half the Otero County population living within the city limits. Alamogordo today has very little manufacturing and has a primarily service and retail economy, driven by tourism, a large nearby military installation and a concentration of military retirees.[50][51] In 2006 the per capita income in Otero County was $22,377 versus per capita income in New Mexico of $29,346.[52]

Alamogordo was founded as a company town to support the building of the El Paso and Northeastern Railroad,[13]: 2  a portion of the transcontinental railway that was being constructed in the late 19th century. Initially its main industry was timbering for railroad ties.[13]: 1  The railroad founders were also eager to found a major town that would persist after the railroad was completed; they formed the Alamogordo Improvement Company to develop the area,[13]: 5  making Alamogordo an early example of a planned community. The Alamogordo Improvement Company owned all the land, platted the streets, built the first houses and commercial buildings, donated land for a college, and placed a restrictive covenant on each deed prohibiting the manufacture, distribution, or sale of intoxicating liquor.[13]: 1, 9, 13, 44

Tourism became an important part of the local economy from the creation of White Sands National Monument in 1934.[13]: 53  Construction began on the Alamogordo Army Air Field (the present-day Holloman Air Force Base) in 1942, and the Federal government has been a strong presence in Alamogordo ever since.[13]: 39, 53  Education has also been an important part of the local economy. In addition to the local school system, Alamogordo is home to the New Mexico School for the Blind and Visually Impaired, founded in 1903, and a branch of New Mexico State University founded in 1958.[13]: 44, 58  The largest non-government employer in the city is the Gerald Champion Regional Medical Center with 650 employees in 2008.[53]

Holloman Air Force Base, located approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) west of the city limits, is the largest employer of Alamogordo residents, and has a major effect on the local economy. According to some estimates, Holloman accounts for half of the Alamogordo economy.[54][55] According to the 49th Fighter Wing Public Affairs office, as of January 2008 Holloman directly employs 6,111 personnel with a gross payroll of $266 million. It indirectly creates another 2,047 jobs with a payroll of $77 million. The estimated amount spent in the community, including payroll, construction projects, supplies, services, health care, and education, is $482 million.[56]

An estimated 6,700 military retirees live in the area. Counting both USAF and German Air Force personnel there are 1,383 active military and 1,641 military dependents living on base and 2,765 active military and 2,942 military dependents living off base.[56] After 27 years of training at Holloman, the German Air Force left in 2019. They relocated their pilot training to Sheppard Air Force Base in Texas.[57]

Future Combat Systems is a wide-ranging modernization project of the US Army. Much of the work will be done at Fort Bliss, with some at White Sands Missile Range and some at Holloman Air Force Base. Alamogordo is expected to get some economic benefit due to its proximity to these three bases.[58]

Otero County Economic Development Council is a nonprofit organization founded in 1984. Its focus has generally been on job creation and recruiting and expanding businesses in Otero County, including helping them satisfy business regulations in New Mexico and lining up funding.[59][60] Its role expanded in 2000, when Alamogordo passed an Economic Development Gross Receipts Tax. OCEDC continues to work to attract businesses, but now it also helps develop the incentive packages that will be paid by the new tax, and a portion of the tax receipts go to fund OCEDC's operating expenses.[61] Formal economic development plans have been adopted by Alamogordo[62] and by Otero County.[63]

OCEDC has recruited several new employers by using financial incentives. A 1-800-Flowers call center opened in November 2001 and received $1.25 million in city rent abatements, a 50% reduction in property taxes from Otero County, and $940,000 in plant training funds from the State of New Mexico.[64][65] A Sunbaked Biscuits cookie factory opened in 2006 and received $800,000 in job-training incentives from the state.[66] When the company went out of business in 2007, Marietta Baking took over the cookie factory and received interest-free loans, job-training incentives, and partial forgiveness of indebtedness for job creation.[67][68] A branch office of PreCheck Inc., a company performing background checks of health-care workers, opened in 2006. PreCheck received $2.4 million in high-wage job creation tax credits, $1.5 million in job-training subsidies, $1.5 million in capital outlay money for roads and infrastructure, a $625,000 allocation from City of Alamogordo for upgrading sewer lines in the area, and 20.8 acres of land from Heritage Group, a developer.[69]

The Otero County Film Office,[70] an office of Otero County Economic Development Council, promotes film-making in Otero County by publicizing potential locations in the county and New Mexico's film financial incentive programs[71] and by recruiting extras for film productions. It sponsors the Desert Light Film Competition for middle and high school students to encourage learning about the film industry.[72] The 2007 film Transformers spent $5.5 million in New Mexico and $1 million in Alamogordo.[73]

There are two amateur theatrical groups in Alamogordo. Alamogordo Music Theatre[74] produces two musical productions annually at the Flickinger Center for Performing Arts. The NMSU-A Theatre on the Hill produces an annual spring performance for young audiences at the Rohovec Fine Arts Center on the New Mexico State University at Alamogordo campus,[75][76] and an annual Fall performance for general audiences.[77][78]

The Earth Day Fair is held annually at Alameda Park Zoo. It features a butterfly release, a science fair, activities for children, and information booths from local health agencies and nonprofits.[79]

Otero County Fair is held annually at the County Fairgrounds. It features a rodeo, animal judging, food and game booths, and carnival rides. Nonprofit and government agencies set up information booths in the exhibit hall.[80]

The Cottonwood Arts and Crafts Festival is put on each Labor Day Weekend in Alameda Park by the Alamogordo Chamber of Commerce. It is primarily a showplace for vendors of handmade items, and also features music, entertainment, and food.[81][82]

White Sands Balloon Invitational is held annually. Hot air balloons launch from the Riner-Steinhoff Soccerplex and from White Sands National Park and float over the Tularosa Basin.[83]

New Mexico Museum of Space History is a state museum with the International Space Hall of Fame.[84] Flickinger Center for Performing Arts is a 590-seat theater created in 1988 from a re-purposed movie theater. It hosts concerts and live theatrical performances by touring groups, and is the venue for the local amateur group Alamogordo Music Theater.[85][86][87]

Alamogordo Museum of History collects artifacts related to the history of Alamogordo and the Tularosa Basin. It is a private museum, operated by the Tularosa Basin Historical Society.[88] Among notable items in the collection is a 47-star US Flag; New Mexico was the 47th state admitted to the Union, and US flags were made with 47 stars only for one month, until Arizona was admitted.[89] The Museum shop has a large collection of local history books. The Historical Society also publishes its own series of monographs on local history, Pioneer.[90]

American Armed Forces Museum is a museum on U.S. Route 82 near Florida Avenue that opened in 2011. It collects and displays all kinds of military memorabilia from all wars and military engagements.[91]

The Shroud Exhibit And Museum, located in White Sands Mall, showcases a full-sized back-lit photographic transparency of the Shroud of Turin, a religious relic believed by some to be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ. They also feature a working VP8 Image Analyzer, the only one in the world where one can walk in and interact with this old analog computer. This town was founded the same year (1898) that Secundo Pia took the first photograph of the Shroud which started the modern investigation into the Shroud. This is highlighted in the museum. In 1977 in Albuquerque, they held the conference that resulted in the 1978 study of the Shroud with more scientists from New Mexico than any other state. The displayed photograph was created from the 1978 photographs made by Barrie M. Schwortz as part of the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP). The displays include historical background materials, scientific information, kiosks with a variety of information, videos available for viewing and an exhibit of electronic image analysis of the shroud, among other interesting artifacts.[92][93][94]

The Alameda Park Zoo, the oldest zoo in the southwestern U.S., is located in the city. Several Union-Apache battles were fought near Oliver Lee Memorial State Park.[95]

The Toy Train Depot, New Mexico's first railroad museum and home of America's Park Ride Train Museum.

A sculpture called "The World's Largest Pistachio" is at McGinn's PistachioLand along U.S. 54.[96]

The Lady of the Mountain Run is held in December at the Griggs Sportsplex.[97] The race consists of a half marathon, 10K, 5K, or corporate cup relay, and raises money for the needs-based Lady of the Mountain Scholarship Fund at NMSU-Alamogordo.[98] Fun run/walks are popular in Alamogordo, although most are one-shot affairs put on as part of some larger event. One recurring event is Walk Out West, a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) walk held each October in Alameda Park Zoo. It incorporates a health fair, live music, and events for children.[99] An offshoot of this is Dance Otero, an informal approach to ballroom dancing as a form of physical exercise that meets throughout the year.[100] Both programs are run through Otero PATH, a local nonprofit that encourages preventive measures for good health.[101]

There are a number of annual sports events. The Tommy Padilla Memorial Basketball Tournament[102] is an annual event held in March. It is an adult tournament that raises money for scholarships for Alamogordo High School students.[103] The Gus Macker 3-on-3 Basketball Tournament is a national program that holds a tournament in Alamogordo each year in May. Prior to 2008 it was hosted by the Alamogordo Chamber of Commerce, and since then by the City of Alamogordo.[104] The city receives 72% of the entry fees and 5% of the gross proceeds taken in by vendors.[104] The event is held annually at Washington Park in conjunction with Saturday in the Park and Armed Forces Day.[105] In 2009 more than 233 teams participated in the tournament.[105] Several golf tournaments are held each year at Desert Lakes Golf Course, including the Robert W. Hamilton Charity Golf Classic.[106]

Alamogordo's sole professional sports team is the White Sands Pupfish, a baseball team that played at Jim Griggs Field from 2011 to 2019, in the independent Pecos League, but did not play in a 4 team, abridged 2020 season hosted in Houston due to pandemic concerns.[107]

Alamogordo has numerous small parks scattered through the city, and a few larger ones. Some notable parks include:[108]

Not inside the city but nearby are several national and state parks. Oliver Lee Memorial State Park is about 10 miles south on U.S. Route 54, offers camping, hiking, and picnicking.[109] White Sands National Park is located about 15 miles (24 km) southwest of Alamogordo along U.S. Route 70. The area is in the mountain-ringed Tularosa Basin valley area and comprises the southern part of a 275-square-mile (710 km2) field of white sand dunes composed of gypsum crystals.[109] The Lincoln National Forest, whose headquarters are in Alamogordo, is a mountainous area that starts about 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Alamogordo and offers hiking, fishing, and camping.[114] The Sidney Paul Gordon Shooting Range, located about 3 miles (4.8 km) north of town at 19 Rock Cliff Road in La Luz, is a supervised range with rifle, pistol, and archery ranges. Several competitions are held at the range each month.[115]

Alamogordo was incorporated in 1912.[13]: 136  It is a charter city (also called a home rule city[116] ), and the charter is included as Part I of the Code of Ordinances.[117] It has a Council-manager government form of government (called Commission/Manager in New Mexico).[117]: Article II  There are seven city commissioners, each elected from a district within the city, on staggered 4-year terms.[117]: Article VII  The city manager is considered the chief executive officer of the city and is tasked to enforce and implement the City Council's directives and policy.[118] The mayor is a member of the City Council. As of 2018, Richard Boss holds the position of mayor.[119]

Alamogordo's fiscal year ends on June 30 each year; thus Fiscal Year 2008 runs from July 1, 2007, through June 30, 2008. The FY 2008 budget projects income of $61,454,402[120]: 7  and expenditures of $73,655,777.[120]: 5  Sources of City government income and their percentages of the whole were:[120]: 7  gross receipts tax (31%), miscellaneous (23%), grants (22%), user fees (19%), and property tax (5%).

New Mexico State University Alamogordo is a two-year community college established in 1958. As of 2016, it has approximately 1,800 students.[121] There are two high schools (including the comprehensive Alamogordo High School), three middle schools, and 11 elementary schools in the Alamogordo Public School District.[122] Prior to 2008 there were two private schools in Alamogordo: Legacy Christian Academy and Father James B. Hay Catholic School (the latter of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Las Cruces).[122] A third private school, Imago Dei Academy, opened in August 2008 and provides a classical Christian education.[123]

The New Mexico School for the Blind and Visually Impaired is a state school located in Alamogordo.[122] The German government formerly operated the Deutsche Schule Alamogordo (German School) for children of German Air Force personnel stationed at the German tactical training center at Holloman Air Force Base until the 2019 withdrawal of German forces.[124] Following this, the aforementioned Imago Dei Academy purchased the building.[125]

Alamogordo Public Library serves Alamogordo and Otero County.[126] The library at New Mexico State University Alamogordo is also open to the public.[127]

The main newspaper in Alamogordo is Alamogordo Daily News (ADN), owned by MediaNews Group. ADN is published six days a week; on Monday, when it does not appear, subscribers receive the El Paso Times.[128] ADN also publishes Hollogram, a free weekly newspaper distributed at the nearby Holloman Air Force Base and covering happenings on base.[129] There was no alternative newspapers published in Alamogordo but The Ink, a free Las Cruces monthly newspaper devoted to the arts, is distributed in the city. There is now however a free online paper operated as citizen journalism produced by 2nd Life Media Alamogordo Town News[130][131] The city government publishes City Profile, a monthly print newsletter that is mailed to all households in the city and is published electronically on the city web site,[132] and Communiqué, a blog with city news.[133]

One television station, KVBA-LD, broadcasts from Alamogordo. It has a religious format, and a weekly local news magazine broadcast Thursday through Saturday.[134][135] Cable television service is provided by Baja Broadband.[136]

There are two commercial radio broadcast companies, WP Broadcasting and Burt Broadcasting; each operates several stations in several formats.[137][138][139] There are two "listener-supported" radio stations that do not carry advertising but depend on sponsorships and donations. KLAG has a gospel music radio format and some live coverage of local events, including many remote broadcasts from civic events.[140] KALH-LP is a low-power FM station that carries a variety radio format, network news on the hour, and local news on some hours.[141] Neither station is an NPR affiliate. The local NPR outlet is KRWG-FM in Las Cruces, which reaches Alamogordo through a local relay transmitter.[142]

Several major motion pictures were filmed in or near Alamogordo. The 2007 film Transformers was shot primarily at White Sands Missile Range, with additional filming at Holloman Air Force Base, both in the Alamogordo area.[143] Its 2009 sequel Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen also prominently featured these two military bases.[144] The 2009 film Year One was shot partly at White Sands National Monument, near Alamogordo.[145] Alamogordo was one of the fourteen cities profiled in the 2005 documentary 14 Days in America.[146][147] The Otero County Film Office maintains a list[148] of films shot partly or wholly in Alamogordo and Otero County.

In May 2013, Alamogordo's City Commission approved a deal for Canada-based film production company Fuel Industries to excavate the Atari landfill site.[149] Fuel Entertainment partnered with Xbox Entertainment Studios and Lightbox to make a documentary about the massive 1983 Atari video game burial, said to be one of the gaming culture's greatest urban legends. On April 26, 2014, video game archaeologists began sifting through years of trash from the old Alamogordo landfill.[150] The first batch of E.T. games was discovered after about three hours of digging,[151] and hundreds more were found in the mounds of trash and dirt scooped by a backhoe.[152] In the deal between the City of Alamogordo and Fuel Entertainment regarding the excavation, Fuel Entertainment was to be given 250 games or 10 percent of what was found.[150]