For Intermediate Level Players

Joseph Harfouch

Oud Explorations

For Intermediate Level Players

Joseph Harfouch

Shortwave Press

Copyright @Joseph Harfouch 2018

This book is copyright.

Apart from fair dealings for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act,

and apart from pieces that are covered by a Creative

Commons Attribute ShareAlike license as indicated in the book, no part may be reproduced

by any process without a written permission from the author or the publisher.

You can contact the publisher at : publisher@shortwavepress.com

Some pieces that are composed, transcribed or modified significantly by the Author,

as well some other pieces are available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License,

or similar public domain licenses. These are indicated in the book. These pieces can be used without the

need to seek permission as long as the terms of the license are adhered to.

The terms of the Creative commons License that is most often used in this book is

available at the following web site:

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

ISBN 978-0-6482833-0-0

For all the friends that I met through music

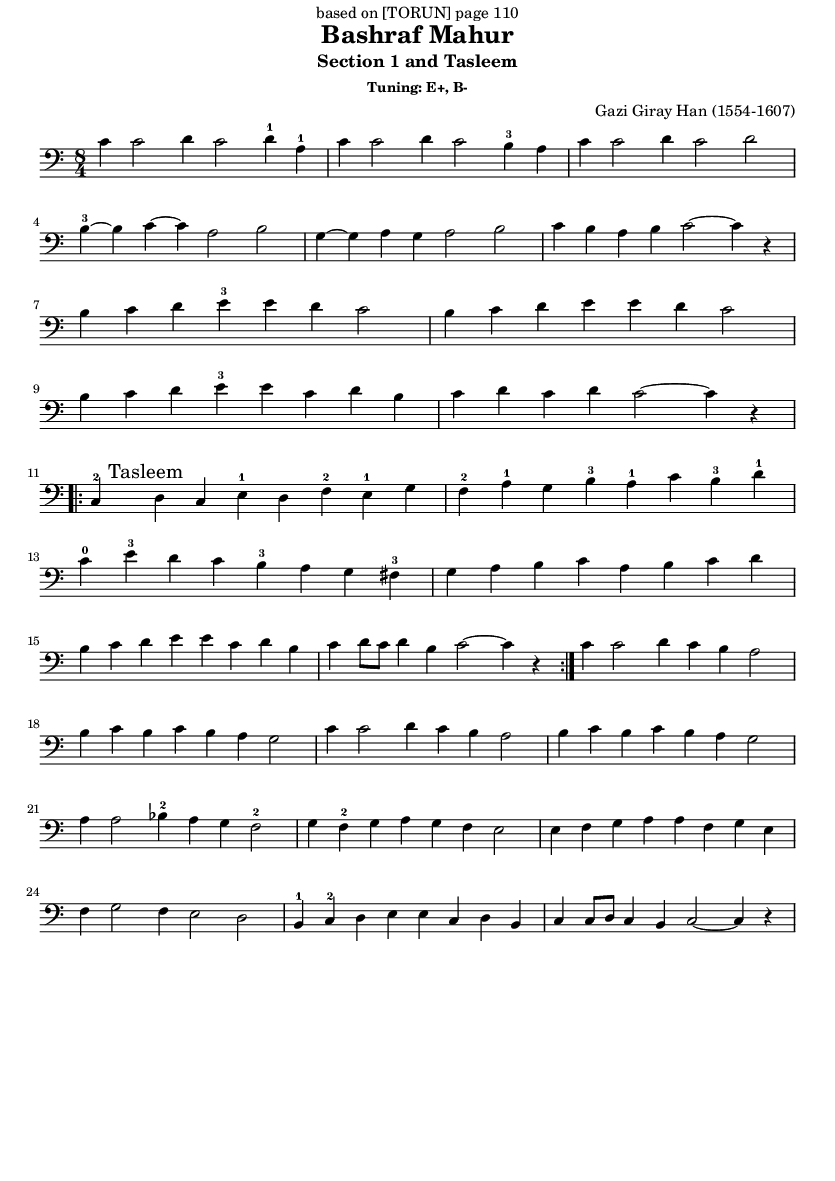

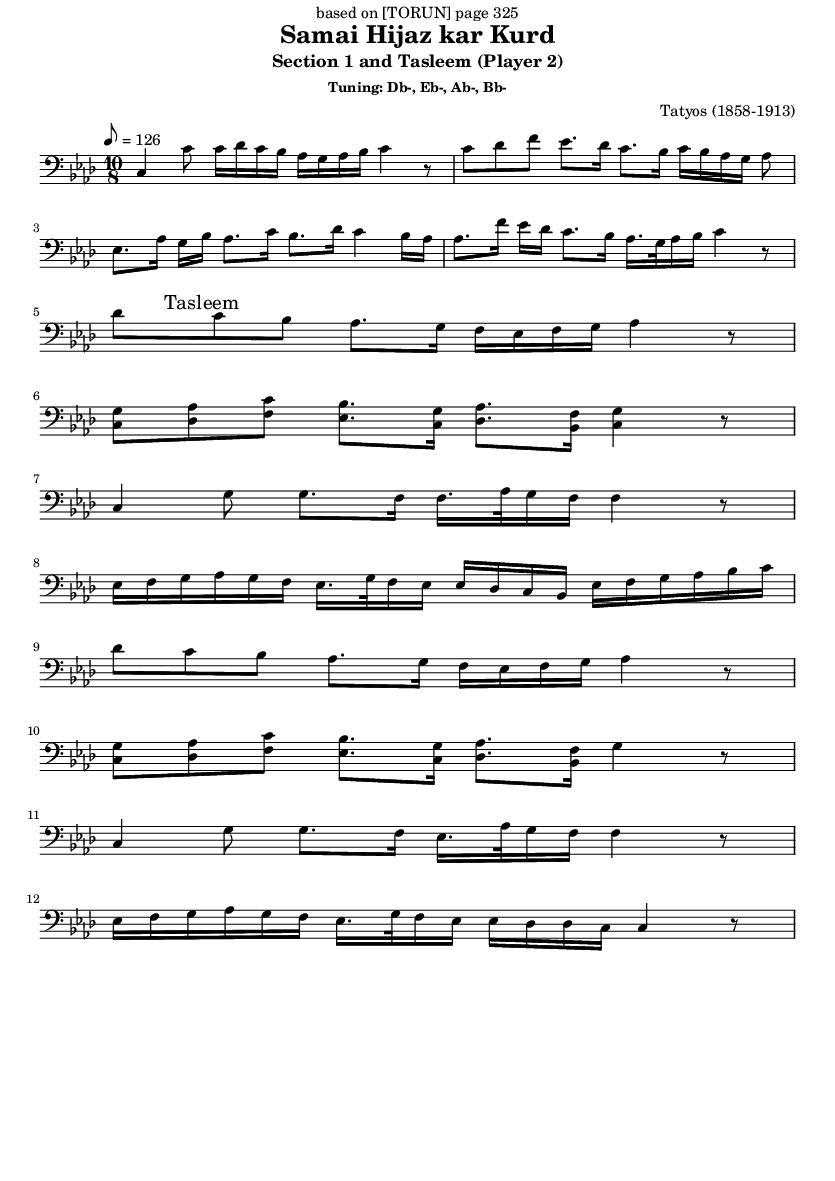

Thanks for Mr Mutlu Torun who many years ago authorized the use of some of the pieces of his book "UD Metodu" in this book. The permission was kindly given in July 2012, but it took me few years after that to finish the book because of the large work involved in transcribing the pieces and producing the book, and because of my other work commitments.

This book was possible through the use of open source tools. The Lilypond music engraving program was used to typeset the music. Latex was used to typeset the book.

Thanks also to Ms Shona Wong for her work in designing the Shortwave Press Logo, and the book cover, and in her help for preparing the book for print.

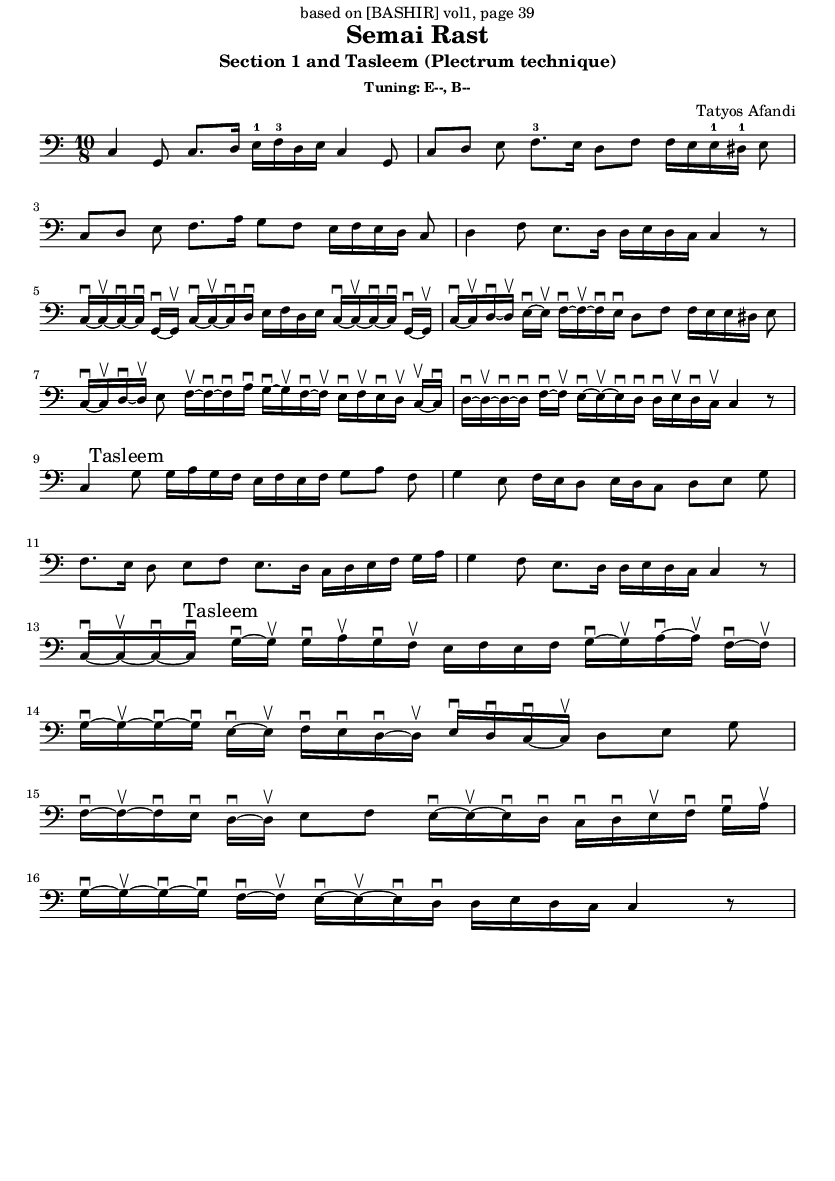

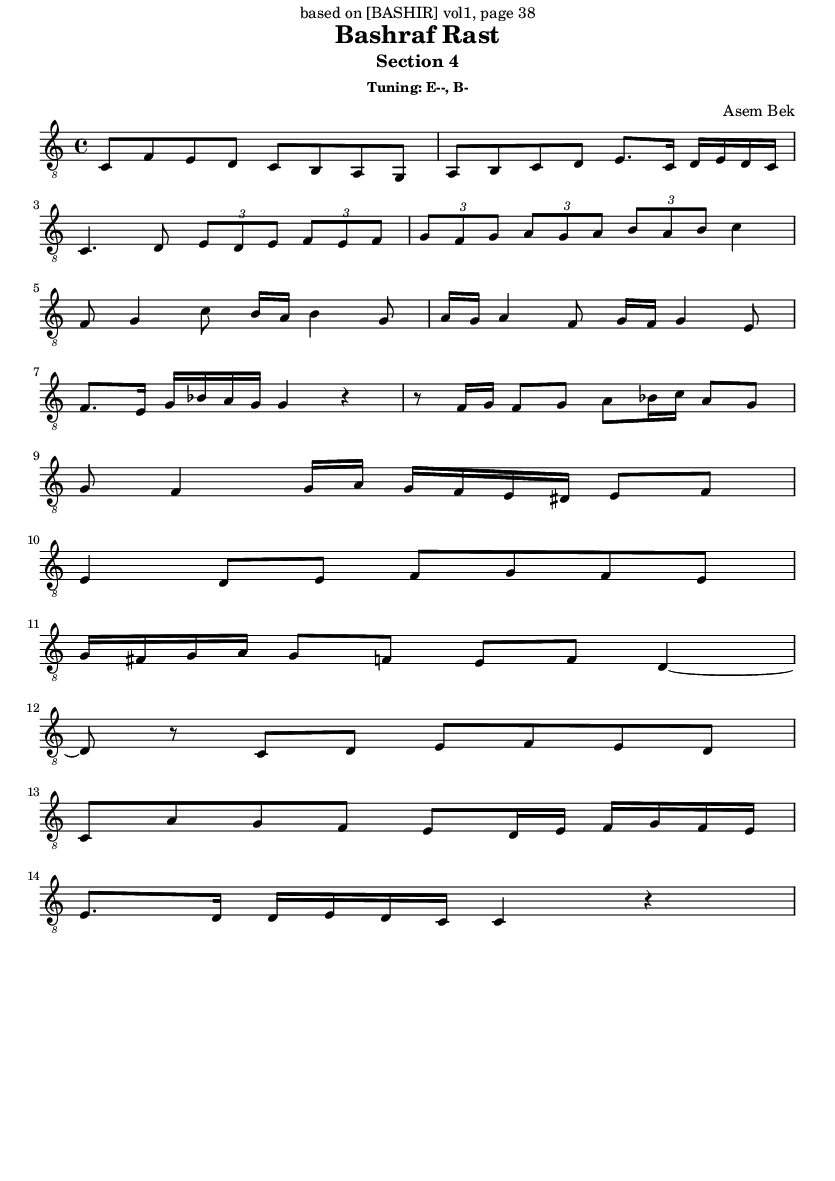

Some extracts were also used from the books of Jamil Bashir, Fouad Awad, Ibrahim Ali Derwishe, George Farah, and Taymour Yousuf. These pieces are attributed in the book.

The book is written for oud players from English speaking backgrounds who wish to advance to an intermediate or more advanced level of oud playing.

There are quite a few books and a lot of free information that is available on the Internet for those that wish to take up this beautiful instrument. They deal with the basics of how to hold and tune the instrument and how to play simple tunes, and they teach the various Arabic modes.

There are also text books that are written in Arabic or Turkish that introduce more advanced pieces. It is possible to play pieces from these books without understanding the accompanying text, which is usually minimal.

It is easy to reach a basic level of playing on the oud, but it is much more difficult to reach a level where the music playing is engaging and interesting, particularly in solo playing. This book grew out of exercises that I wrote for myself in order to advance on the instrument, after some frustration with my static playing level. I followed the old advice that sometimes the best way to learn a topic is to write a book about it. I have also done this initially while ignorant of the huge effort of writing a book involving music notation, that took years of part time work to finish. I say this to emphasize that this is a book by a learner of the instrument, and not an expert on it. Despite this, I believe there are benefits in a book written at a learning stage. There are many benefits in documenting and conveying learning difficulties and sharing different exercises and techniques which I used to deal with these difficulties.

I also wish to share my love of this instrument and advance its uptake in Western countries, for it represents to me what I love best about Arabic music and culture. The sound of the oud playing classical music provides a balance between discipline and freedom, loneliness and sociability, happiness and sadness. It is a quiet and reflective instrument in a noisy world.

So I provide this book in the hope that it will help those who wish to learn the oud seriously, now or in the future, in the same way that it helped me.

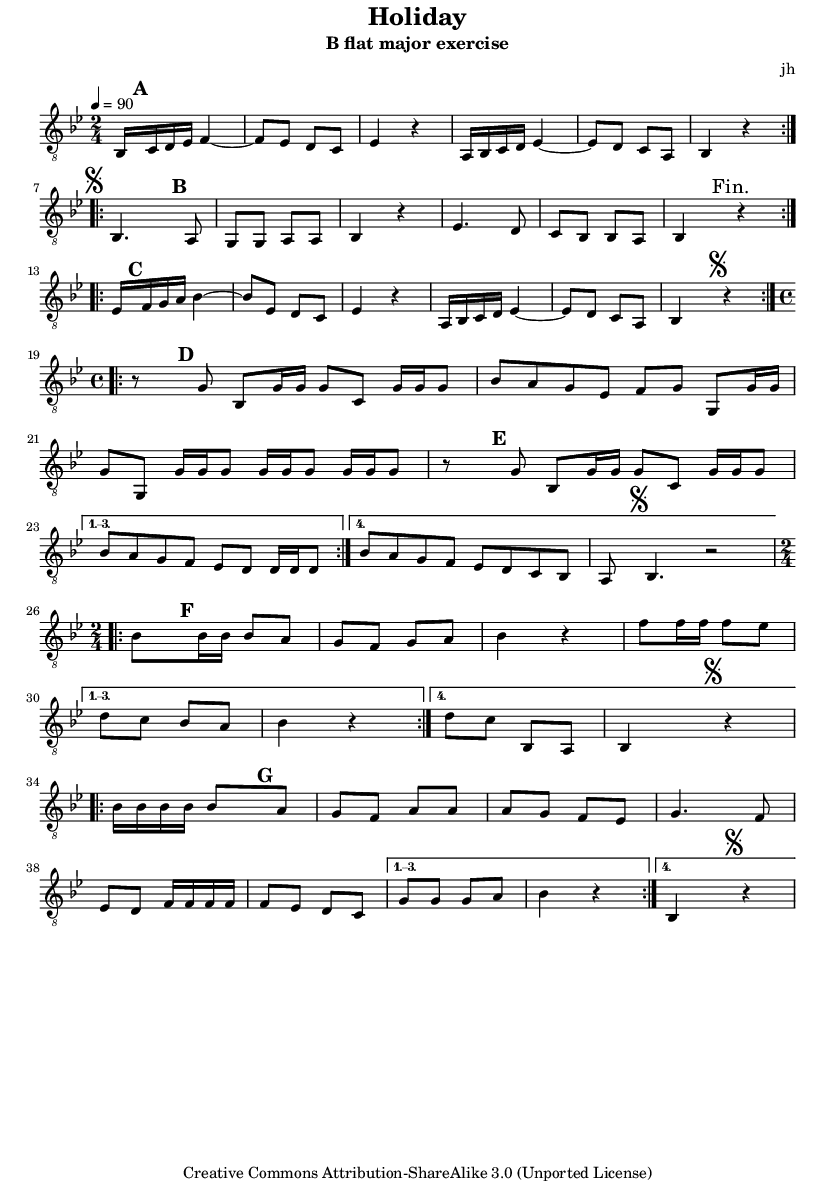

The book is divided into two main parts: technical and modes.

The technical part is the more important one, given the purpose of this book is to help the player advance beyond the beginner stage. This part contains many technical exercises that are aimed at improving the right hand technique, learning to alternate between lower and higher registers, improve left hand technique and so on.

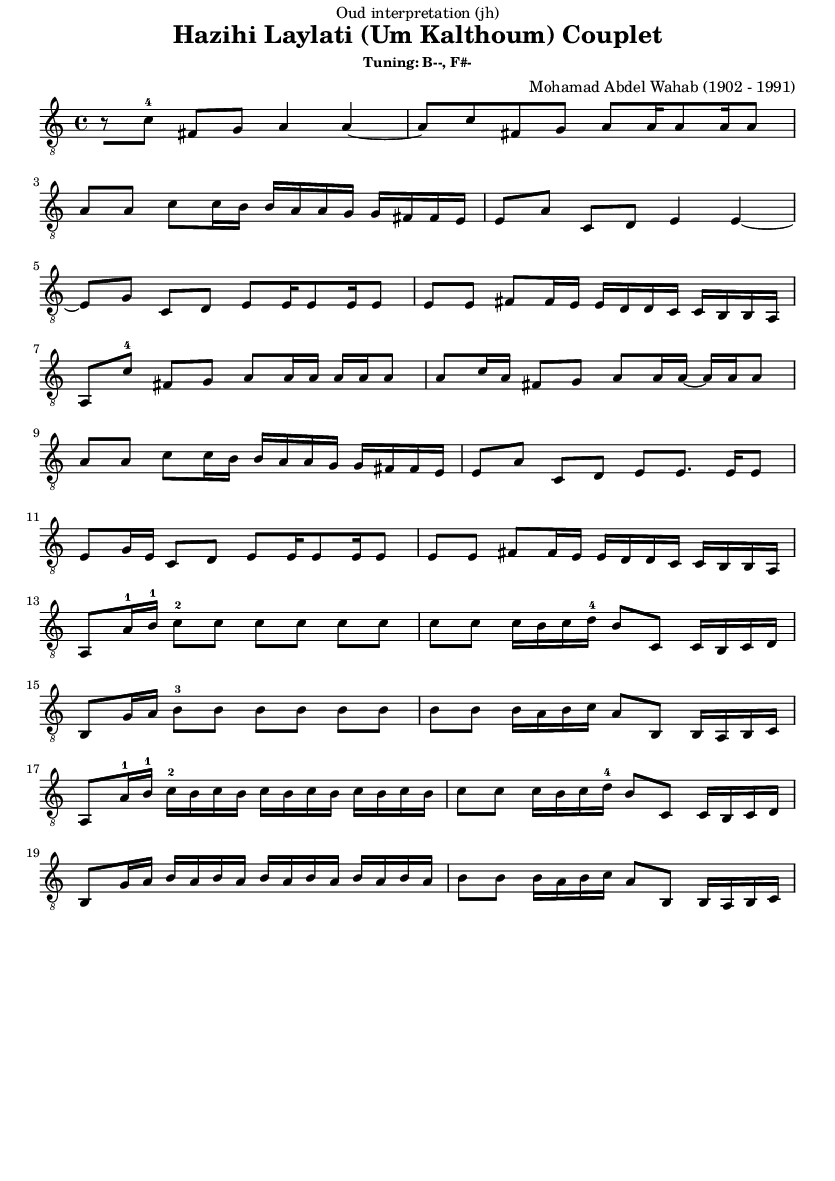

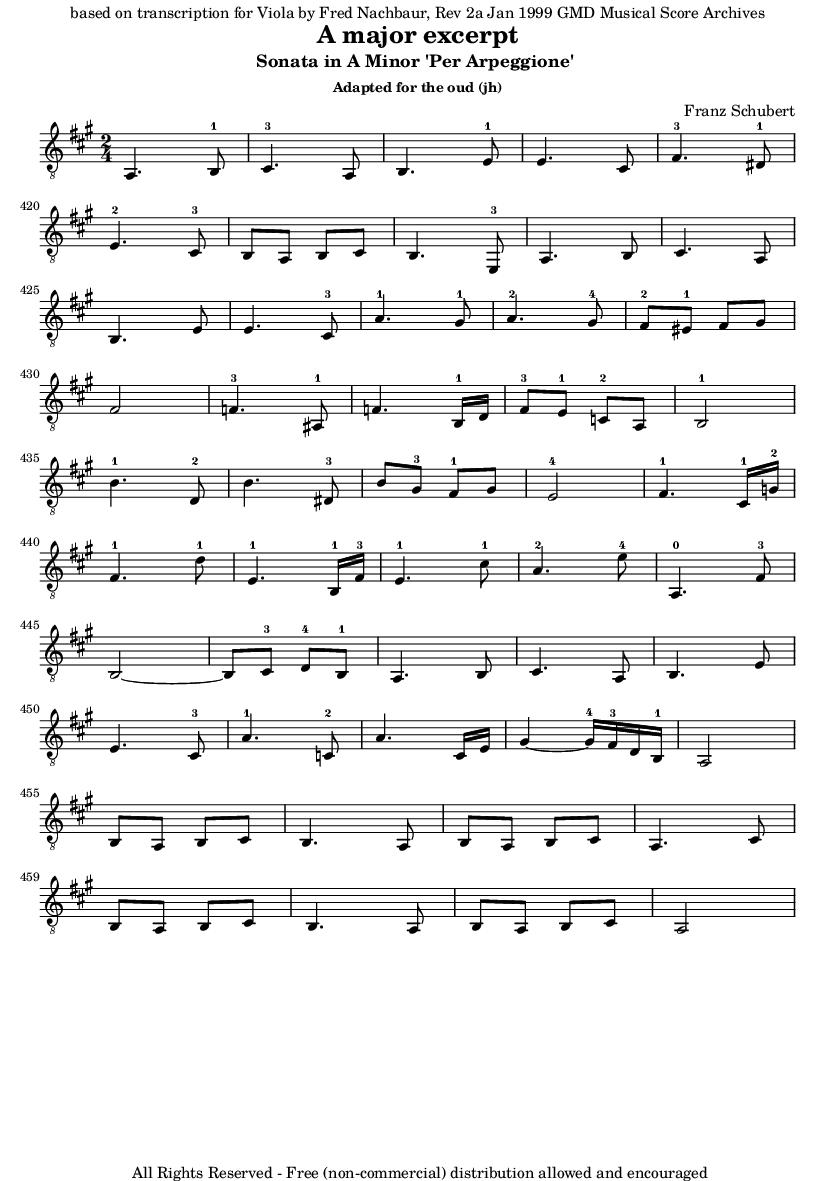

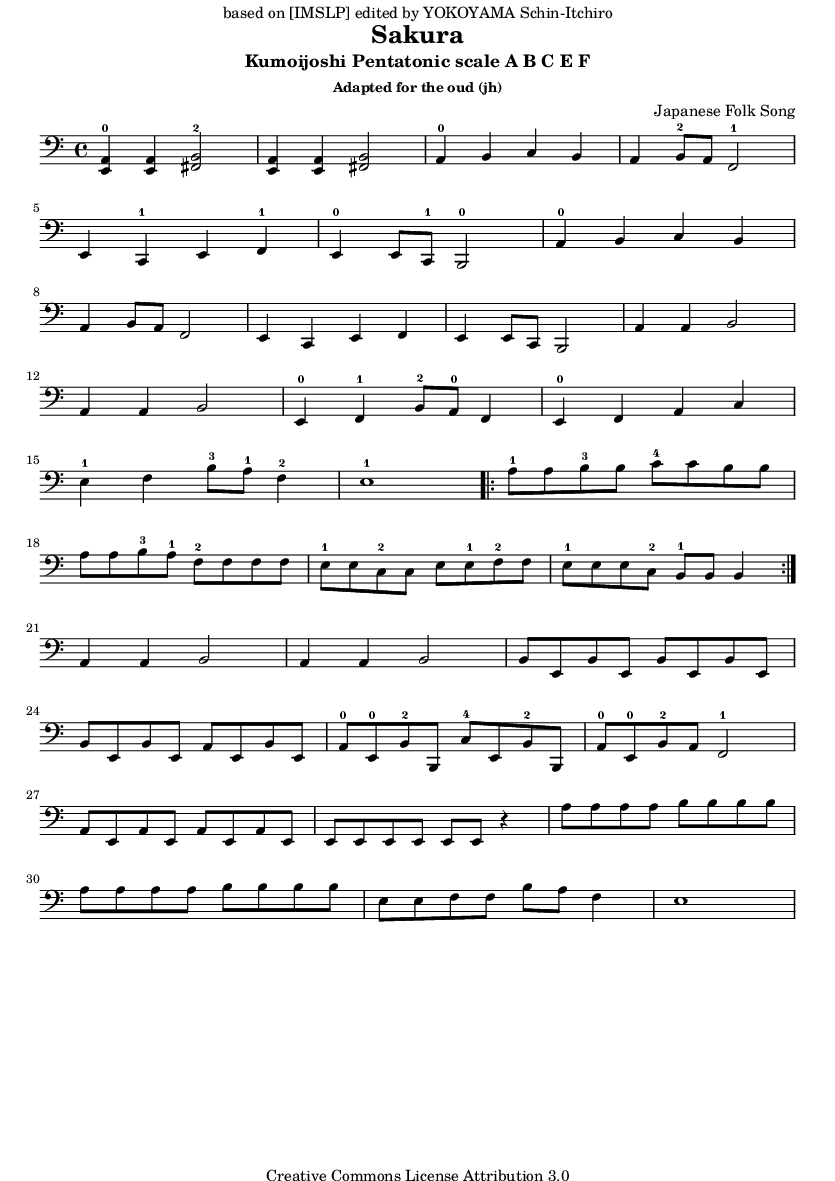

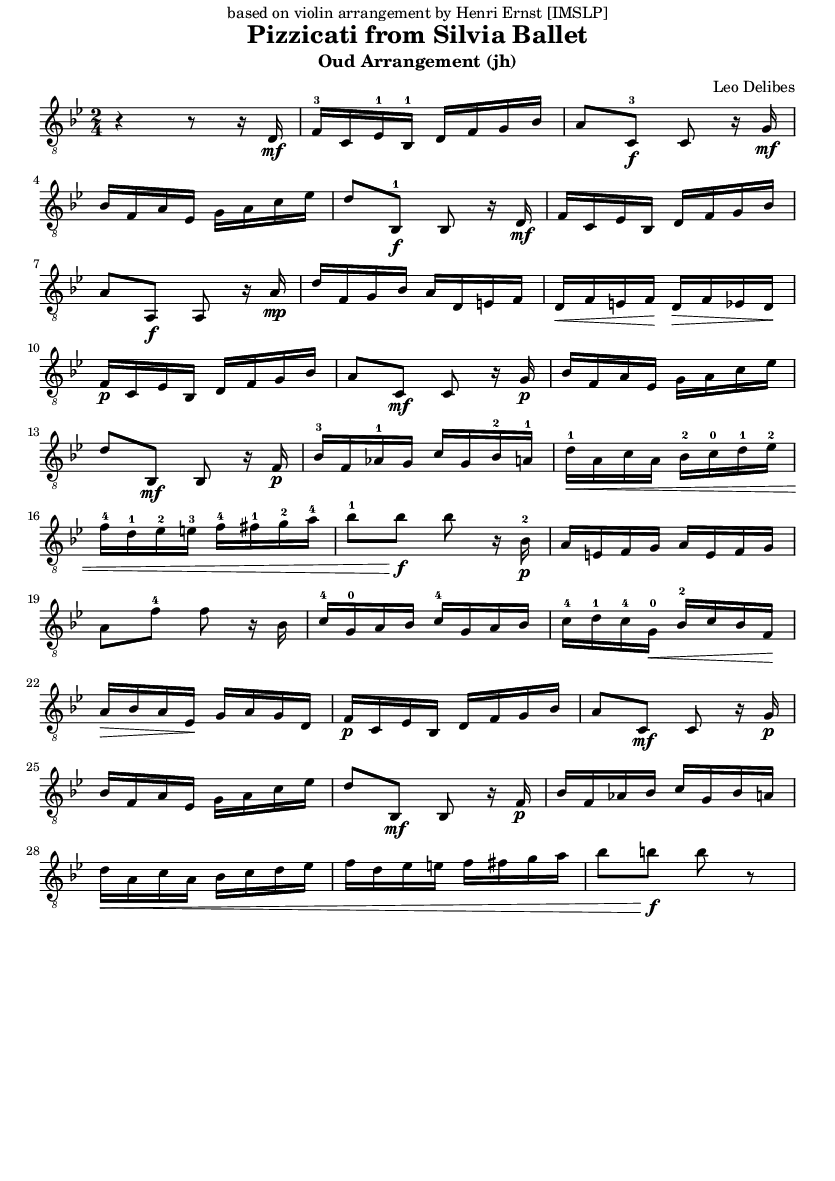

The modes part introduces some of the more important modes of Arabic music, and goes beyond Arabic traditional pieces, to explore the entire range of the instrument. The theme of exploration is central to this book, and it encourages the reader living in a Western society to use the instrument in a new way that may not always be connected with Arabic culture. In this section I introduce pieces that I learned in other contexts, such as pieces by Bach or even some Indonesian gamelan pieces, but the aim is always to explore the instrument and to introduce something that is challenging but playable.

Roaming over such a wide range, means that the pieces are necessarily short in order to keep the book to a manageable size. Most of the pieces are extracts that fit into a single page of music, and the reader is encouraged to refer to other books and sources for the full pieces.

The Lilypond music engraving program was used to typeset the music.

The program is capable of notating semi-flats and semi-sharps as is common in Arabic music notation. It can also indicate more chromatic divisions as is the case in Turkish music notation.

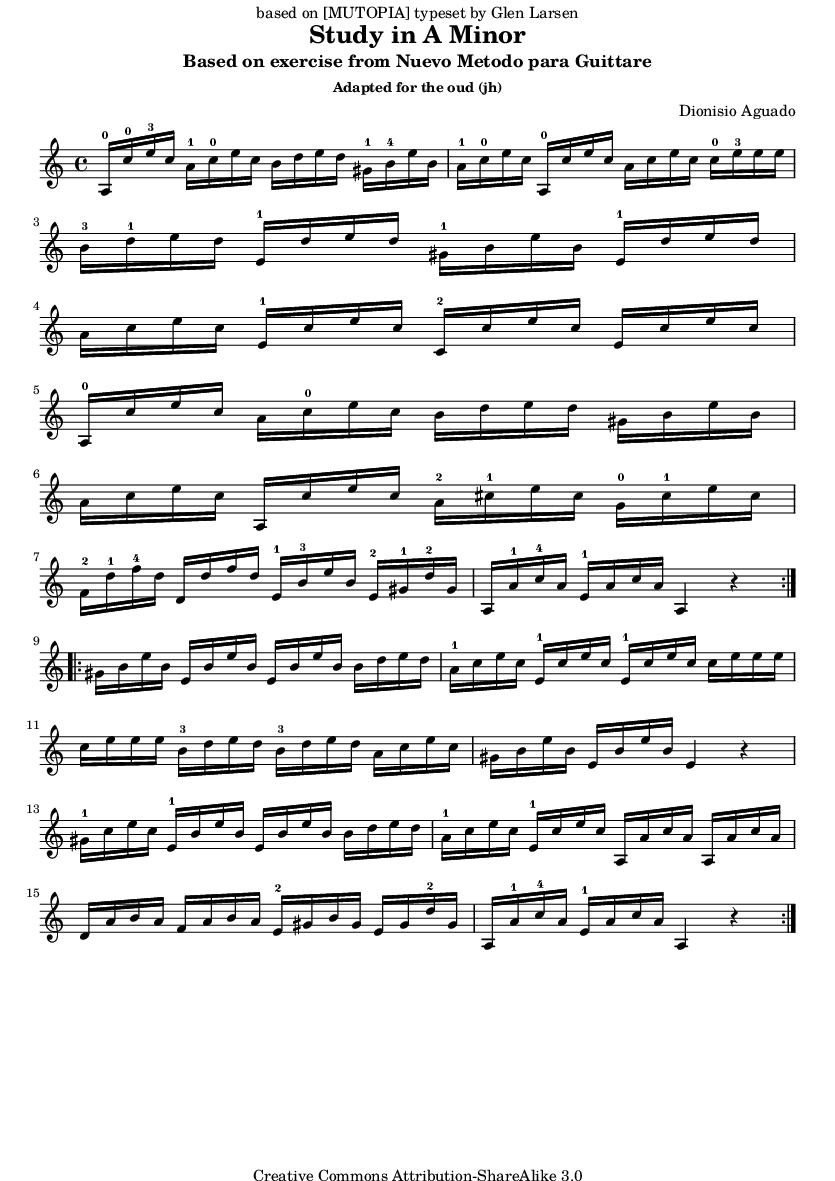

Despite this, I have chosen not to use semi-flats and semi-sharps in music notation, but indicated deviations from the equal temperament piano tuning for each piece.

The fact that I was able to do this for most of the pieces shows that the quarter tone is not a fundamental part of Arabic music. It is perhaps better to think of the modes of Arabic music as consisting entirely of tones and semi-tones in a scale that is slightly different from a minor or major scale. The nature and extent of the difference varies for each mode.

This is not the practice of Arabic or Turkish method books. In Arabic books semi-flats and semi-sharps are indicated separately. Turkish method books go even further and indicate two types of semi-flats and semi-sharps.

Despite its unfamiliarity, adopting this scheme has many advantages, particularly for a Western Audience. We use exactly the same musical notation that is used in Western pieces. We can relate the modes to Western scales with which we are already familiar. We emphasize the fact that the written notation is only a rough indication of the sound, and the only ways to learn the sound of the piece accurately are either to listen to it or to be entirely familiar with the sound of the mode it is in. This scheme might become stretched if the piece is long with many modulations between different modes that need to be indicated beforehand, but it works well for the short piece extracts in this book.

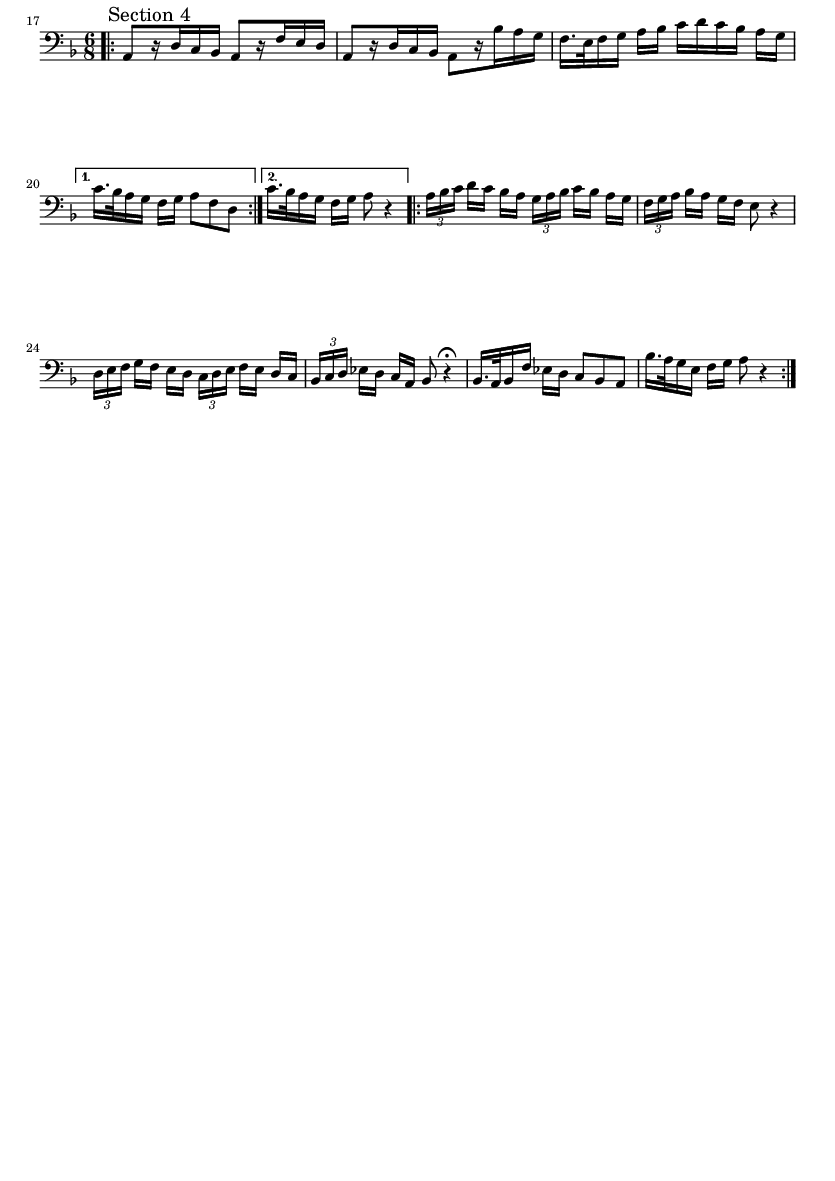

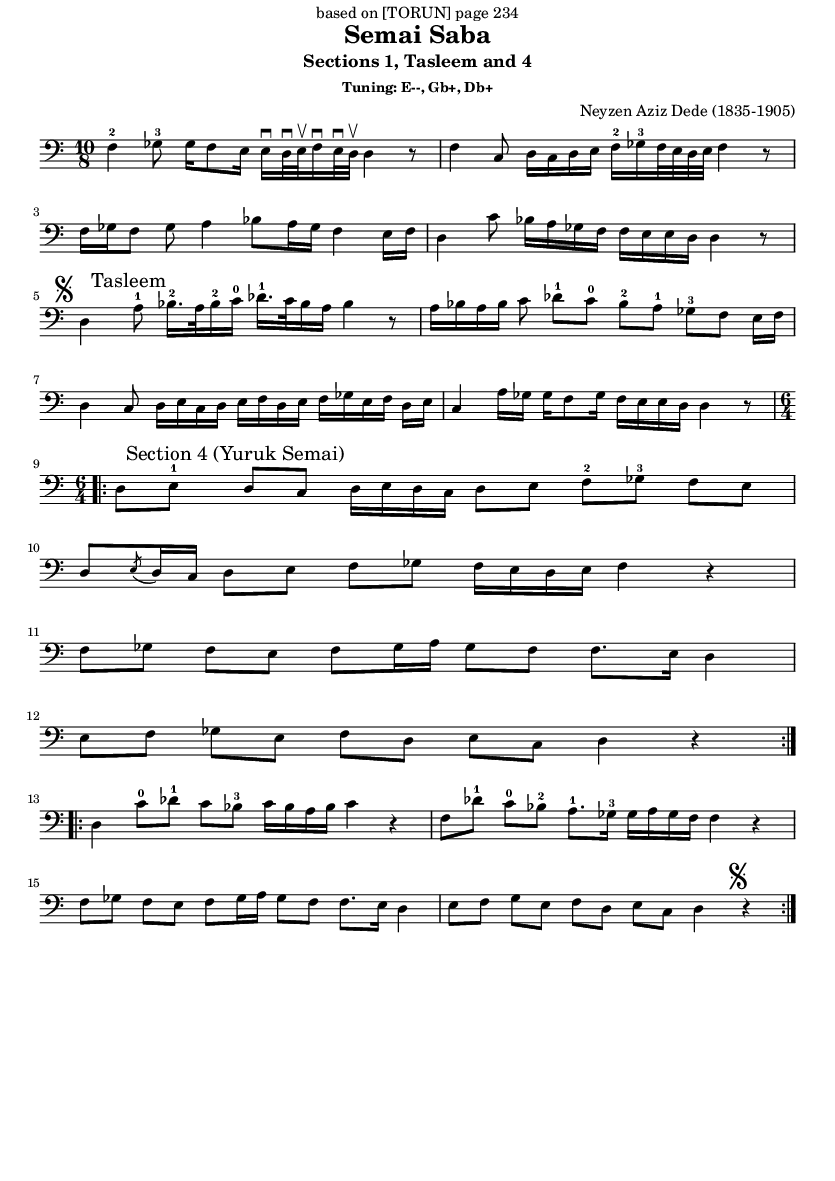

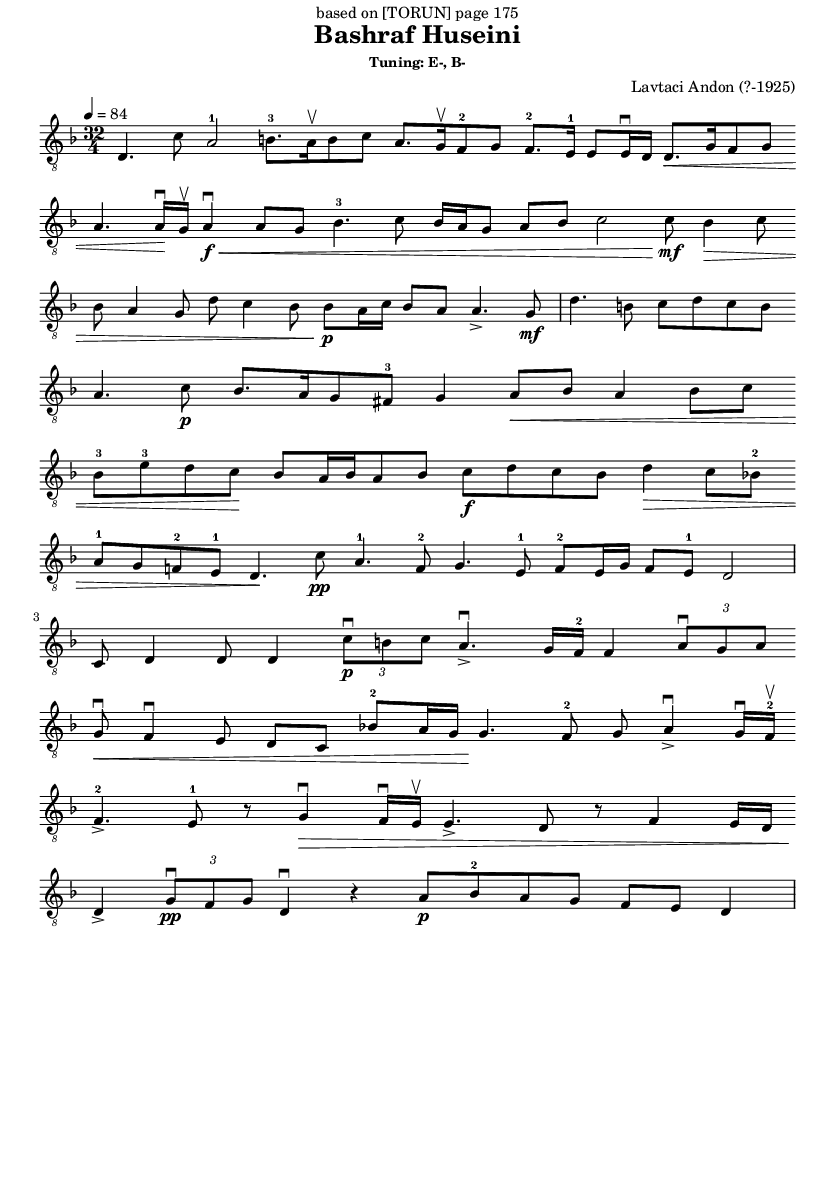

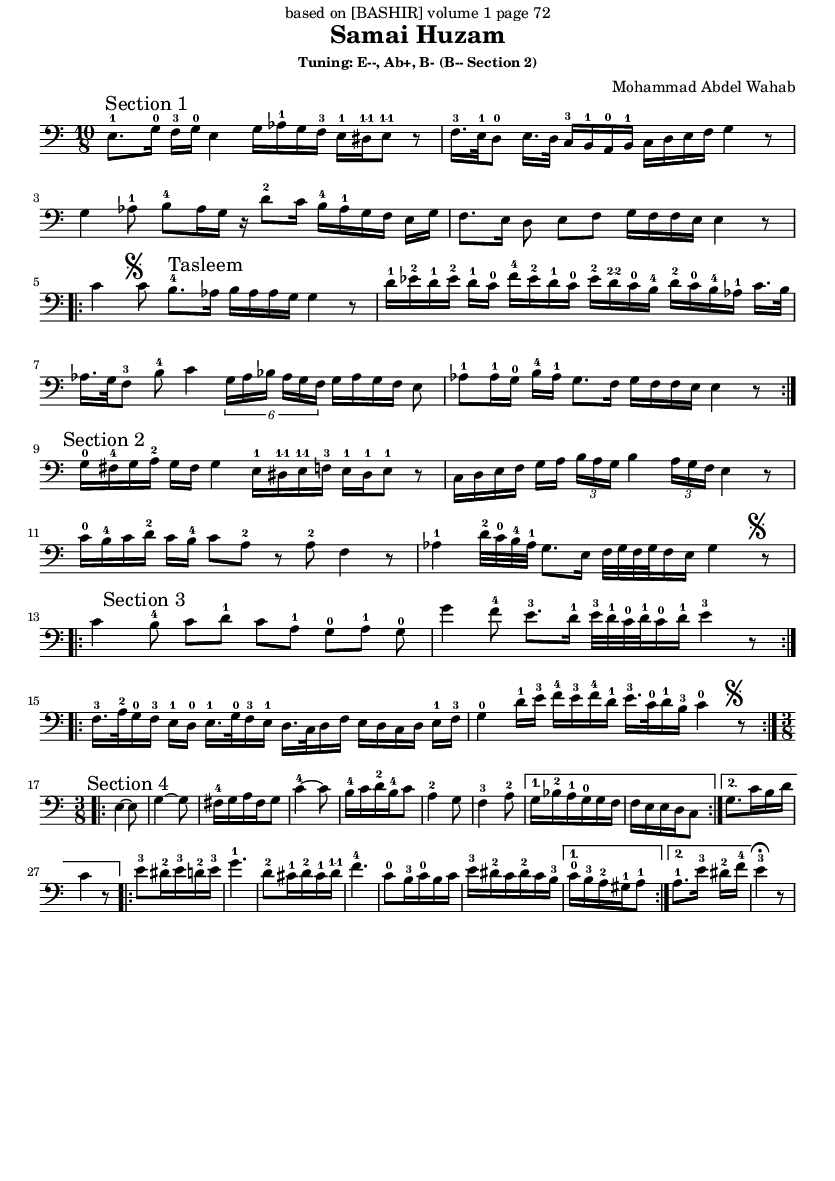

Another deviation from traditional oud method books, is my use of the base clef for many pieces. The base clef better captures the sound range of the oud, but most Arabic oud methods that I have seen use the treble clef and notate the music an octave higher than it sounds. Using the treble clef, much of the music that is played in the low register of the oud lies outside the clef, and it is more difficult to fit the music on a single page. I have used the base clef whenever I had trouble fitting the music on the page, or whenever I felt the music looked better written within the clef, or when the original piece was written in a base clef, such as those borrowed from the cello repertoire. Learning the base clef is not difficult. I learned to use the base clef as I was writing this book. Most of Arabic music does not have large jumps so it is easy to tell what the next note is once the initial note is established. In any case it is not a bad thing to slow down to read the clef while learning. Learning an additional music clef could also be another advantage of using this book.

I use Lilypond to sometimes indicate the suggested left hand finger positions as numbers above the notes, and occasionally the string number to use in a circle above the notes. In numbering strings, the course labeled 1 is the one tuned highest (To C in the conventional oud tuning adopted in this book). Plectrum directions are also indicated in some exercises, using the same Lilypond notation used to indicate violin bow directions.

This is a frustrating issue, because most writers of Arabic oud methods do not indicate the source or attribute the pieces of music that they publish. It is also not clear what the copyright status of most of these pieces are, and when the copyright expires.

Also, despite the Internet I was not successful in contacting the authors and publishers of oud method books in order to obtain permission.

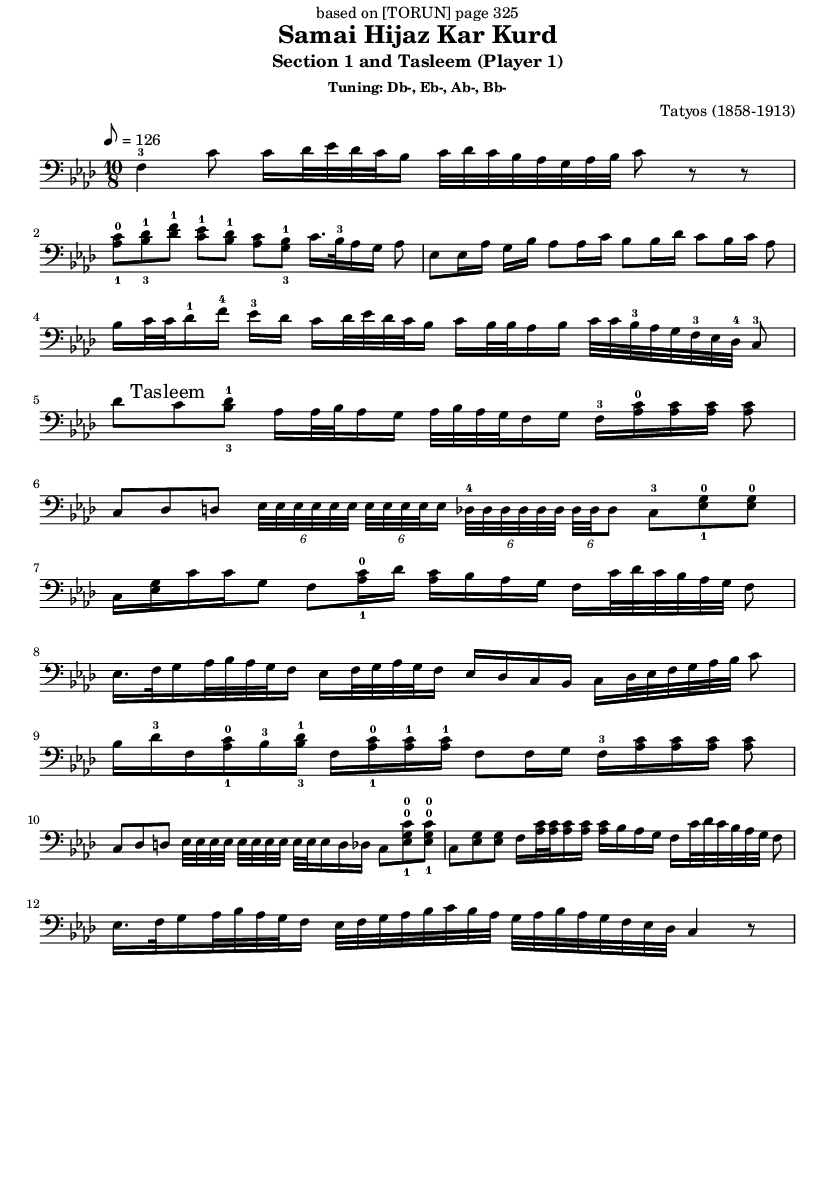

The exception is Mr Mutlu Torun who published an excellent Turkish oud method, and who did kindly respond and give permission to publish the pieces you see in this book.

If a book were to be published at all, then obtaining a copyright for every single piece was not possible. However I did the following steps to mitigate copyright issues :

I favored pieces that were published in the Torun method book.

I favored pieces that had Creative Commons License published on sites such as the Mutopia project or the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP).

I favored pieces that are published in relatively old method books by deceased authors, such as the oud method books of Jamil Bashir.

I kept each extract to a small size, rarely publishing a full piece. I attributed the piece to its source, and I encourage the reader to buy the original sources that contain the full pieces.

So, in order to be able to publish a book at all, I took all care possible and tried to be as fair as possible in my borrowing, and operated on the principle that in this case, it may be easier to seek forgiveness than permission. I hope, that given the very limited profits in this field, that the case to advance the playing of the instrument will supersede any copyright concerns.

In order to make it easier for other writers on this topic in the future, I attributed sources as much as I could. I also nominated new exercises, compositions and transcriptions that I composed as available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license. This means that these pieces can be used and modified without the need to seek permission from me, as long as they are properly attributed and shared on the same basis as explained in the license terms on this site: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

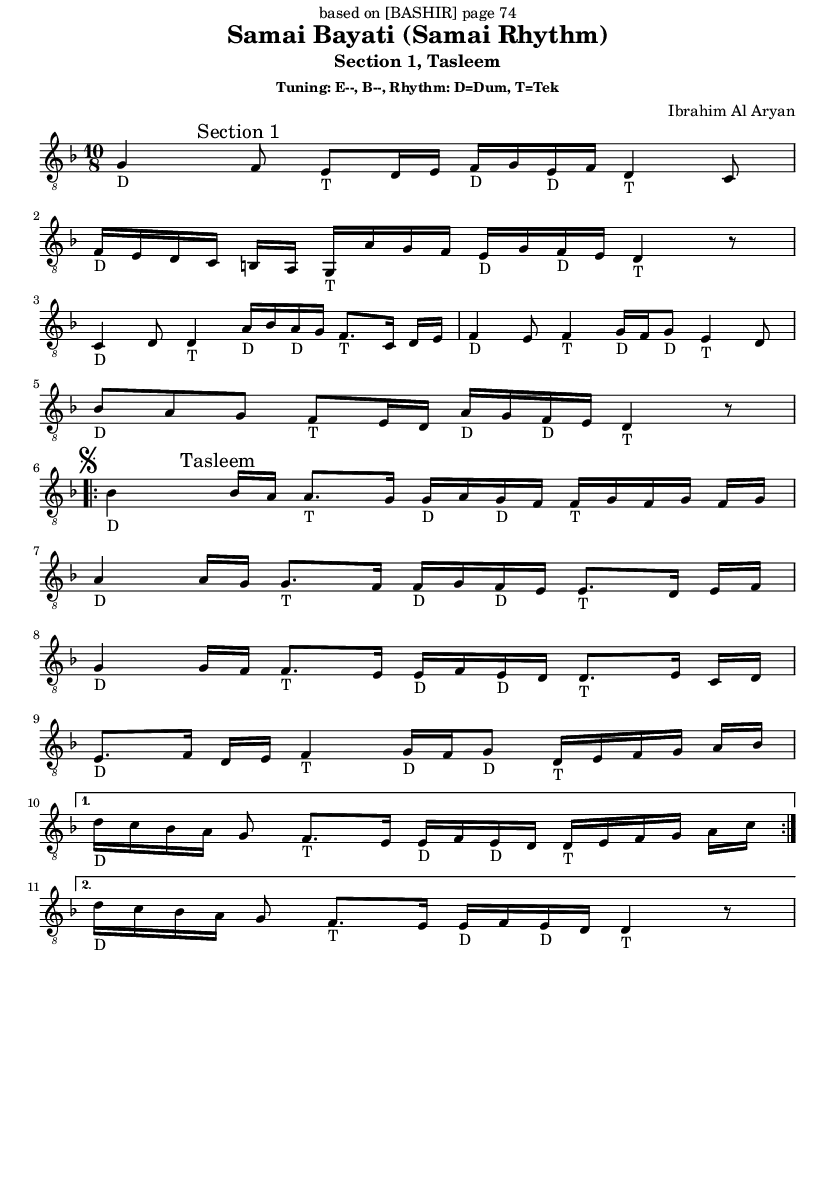

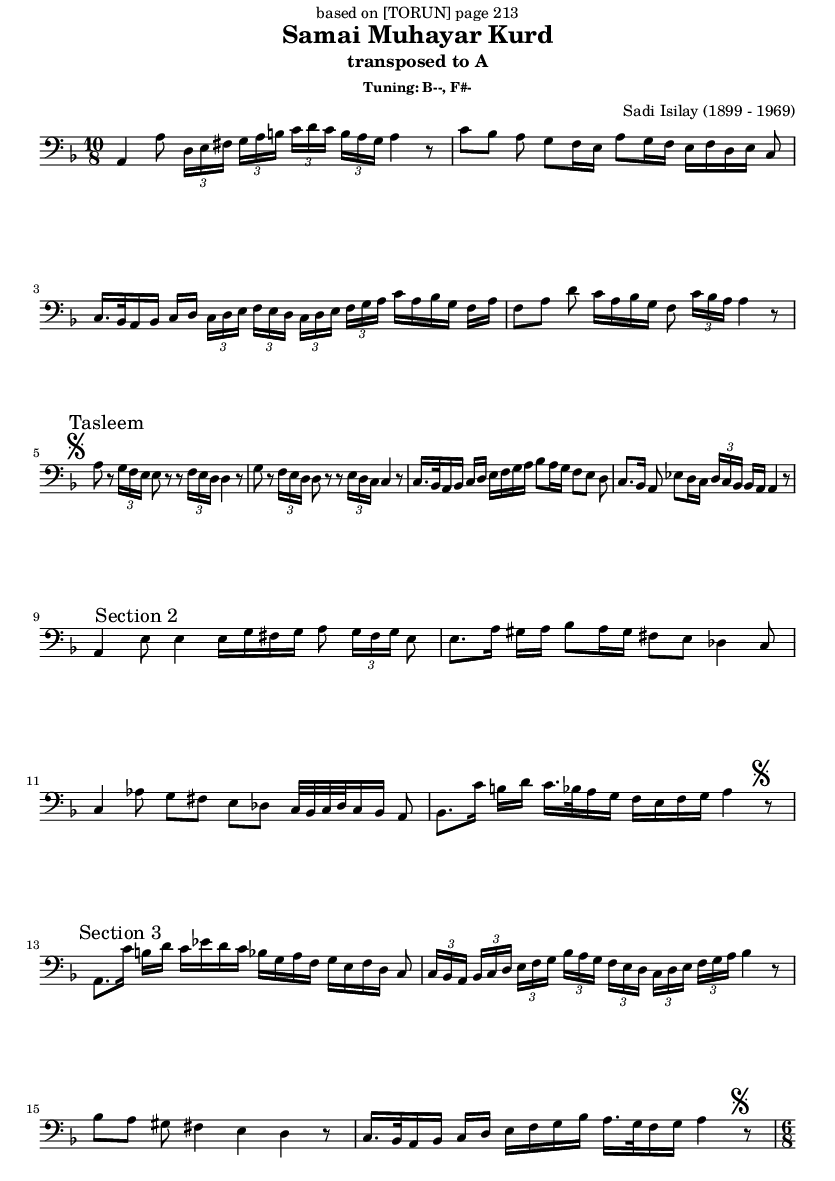

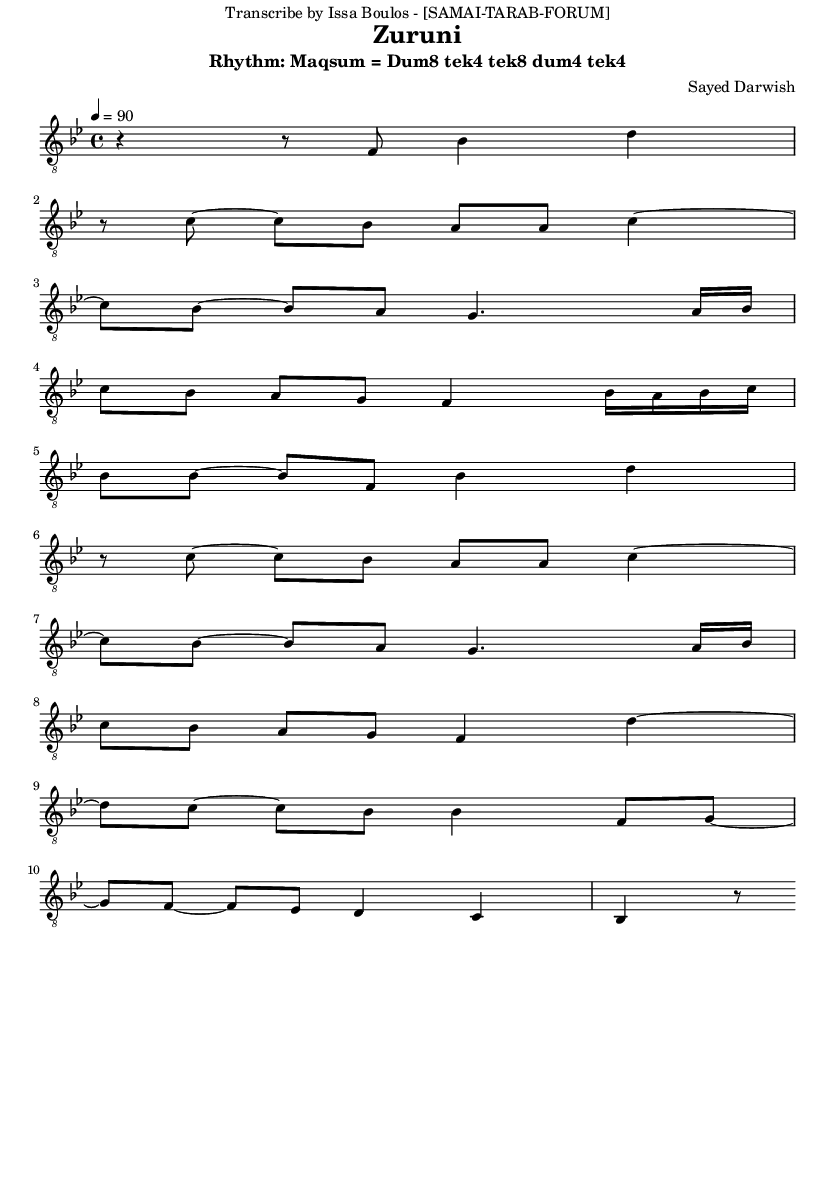

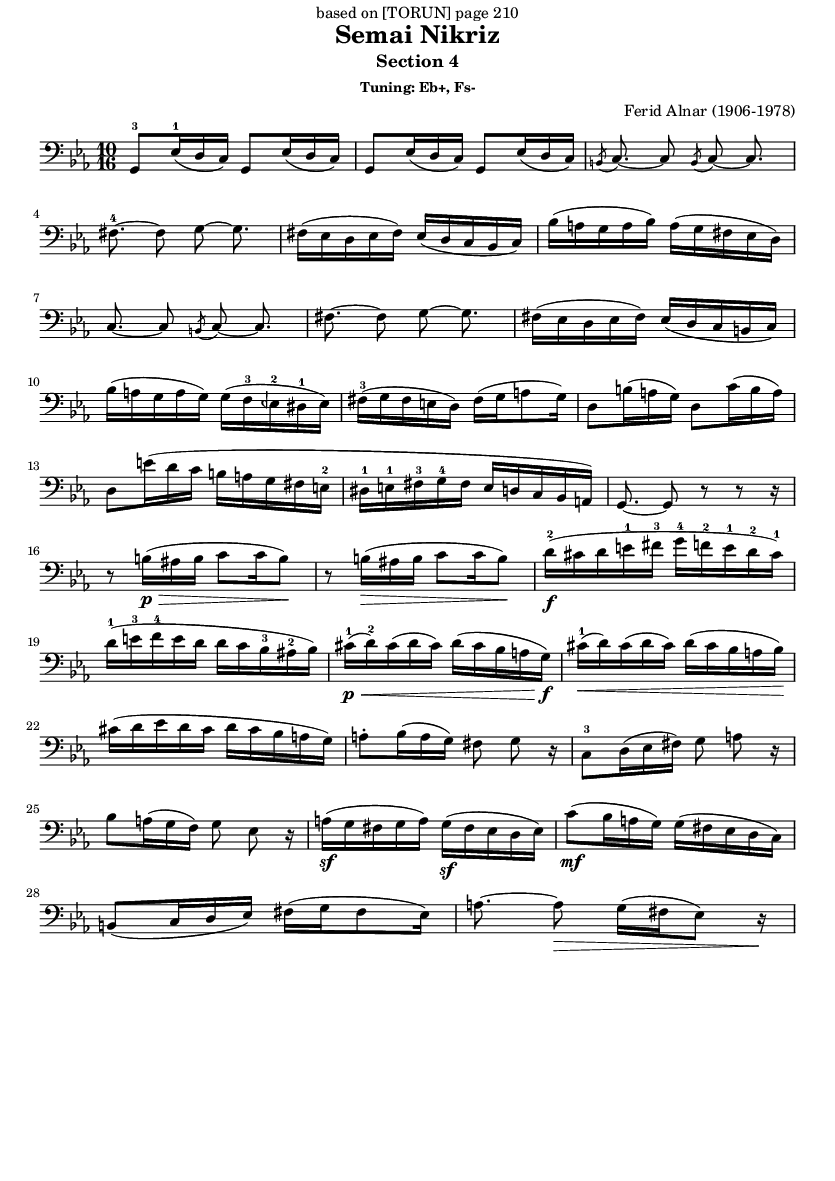

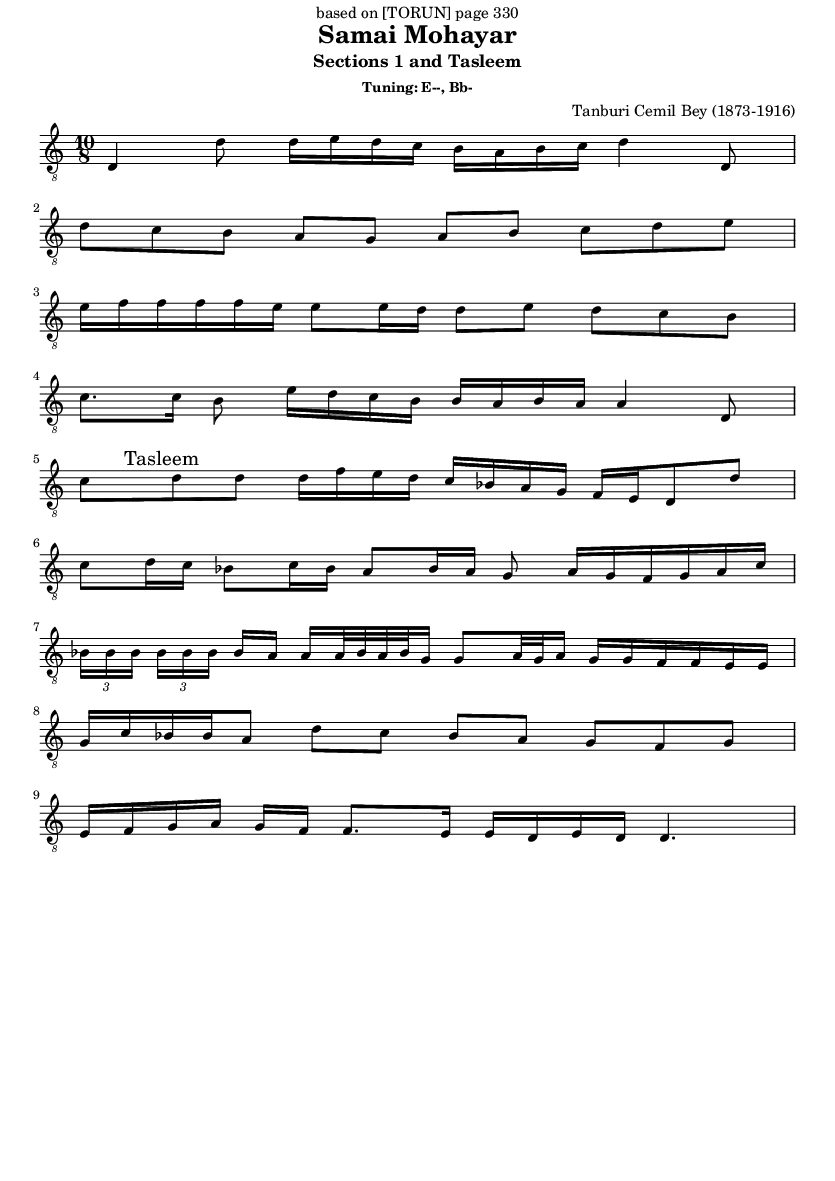

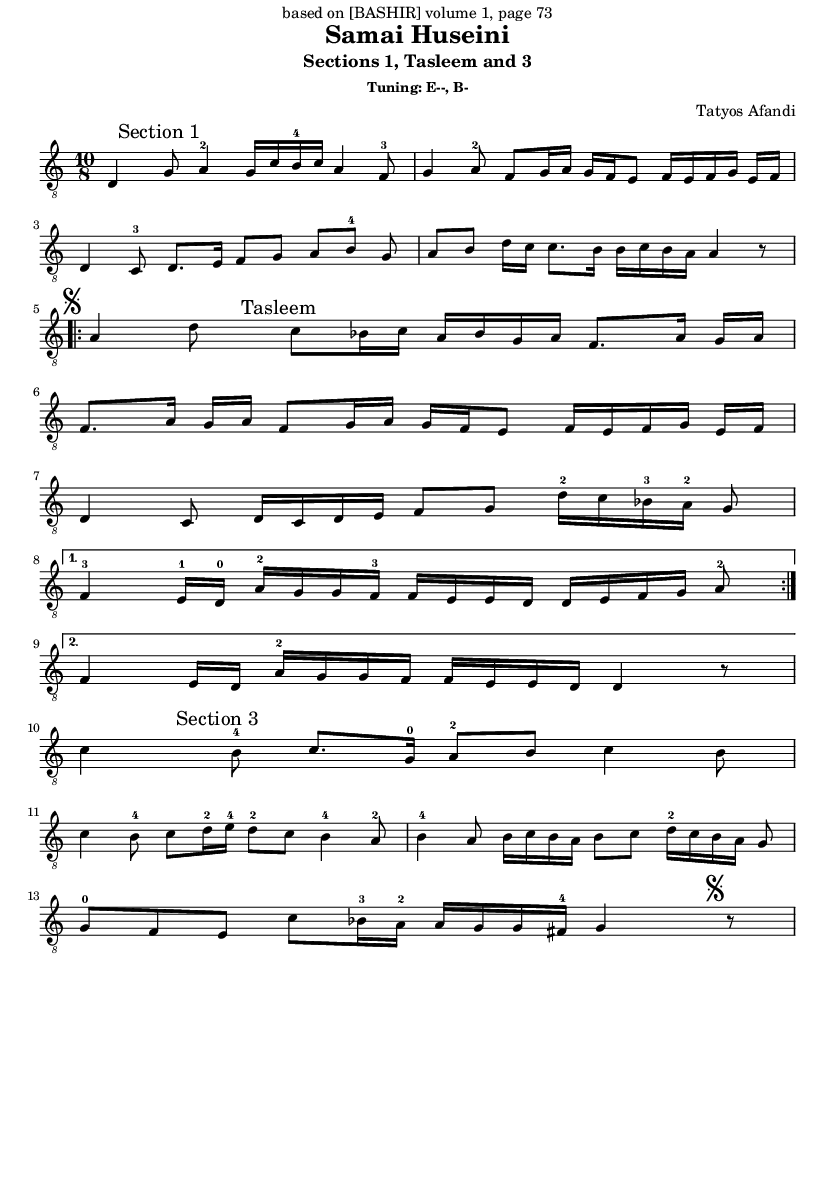

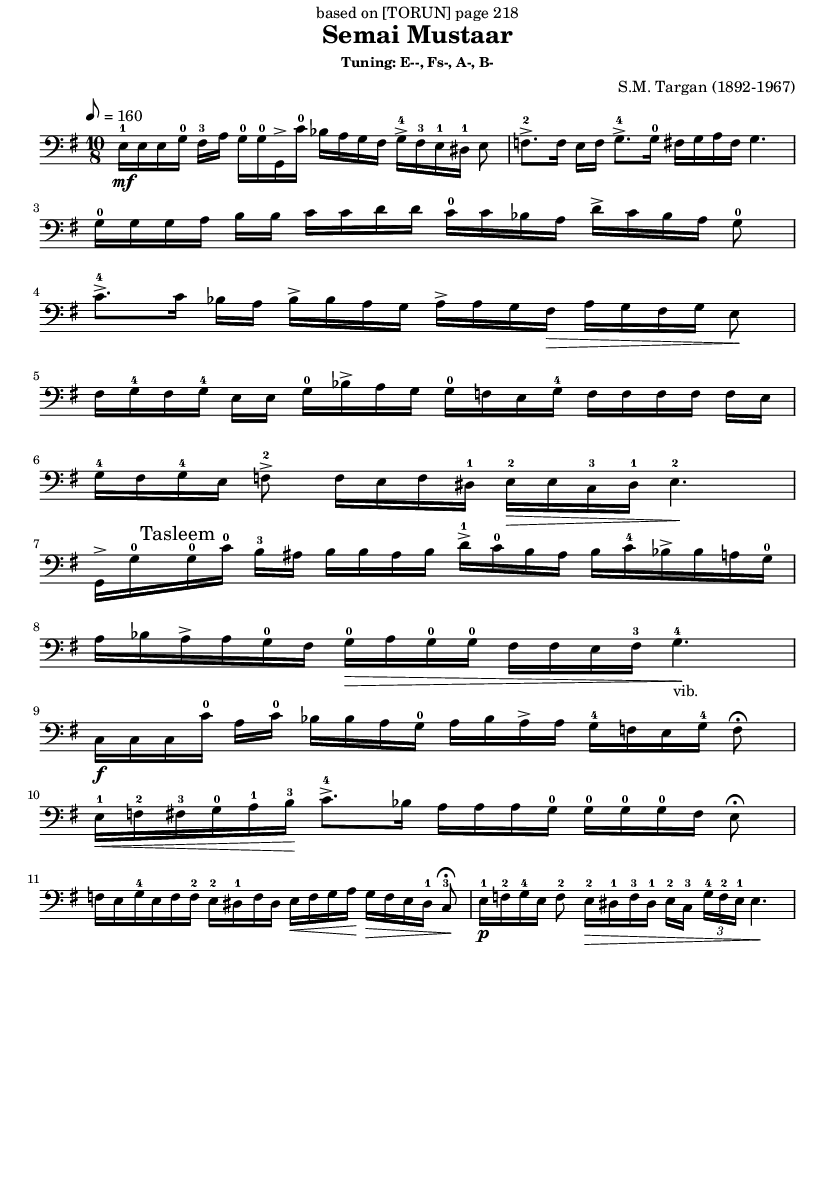

Since Arabic uses different alphabet and has additional sounds that do not exist in English, there is no uniform way of pronouncing or writing Arabic terms in English. The Turkish modern Alphabet is closer to the Latin Alphabet but also has some additional characters. For example the Samai is a form of music that is characterized by a 10/8 rhythm. It is sometimes written as Samai or Samai’i or Semai’i or Samai’ etc. Bashraf is another form that can be spelled in Turkish as Pesrev. Arabic music borrows many of these forms from Turkish music, and the names of the composers are often changed in Arabic. Often the name changes are minor, but sometimes they are radically different. For example The composer Targan is given a totally different name in Arabic which is Haydar or Haidar. Turkish music adds titles to composer names that are often omitted in Arabic text, so the composer Jamil in An Arabic text, is probably the same as Jamil Bek in a Turkish text, Tatyos in Arabic is the same as Tatyos Affandi in Turkish, since Bek and Affandi are Turkish honorific titles and are not part of the name.

To add to the confusion, Composers are often identified by their first name only or are given second names that do not help distinguish them such as honorific titles or their profession as a oud or Keman player, so it is sometimes difficult to be certain that they are the same or different composers, particularly when the first name is common.

Since this is not a book of music scholarship, and the emphasis is more on learning the instrument, I simply wrote the piece titles and composer names preserving the Turkish writing, and transliterating the Arabic writing as closely as possible for each piece. The result is an inconsistent naming convention, but it is an inconsistency that already exists, and will be encountered by anyone who learns Arabic and Turkish music.

Consider joining a musical group. It does not matter if you play an instrument other than the oud in your group. Of course if you can find a group that plays Arabic music, then that is preferable, but it is not essential.

Listen to the sounds around you, and think of music and rhythm as often as you can. This can be done for example while catching the bus, or when going for walks.

Sight read. Even if your sight reading is still weak, you will still be able to sight read at least some parts of a simple piece that you already practiced many times on the oud. You can continue to practice the piece silently by just reading it in your bed or at your desk, and anywhere away from the instrument.

Listen to live performances of classical Arabic music whenever you have a chance.

Order good quality Arabic CDs or buy music downloads and listen to them. Stay away from pirated copies as the low quality sound might put you off Arabic music, especially if you don’t know how good Arabic music should sound like. Focus on instrumental oud pieces, but not exclusively, since a variety of musical experience is also important. You can also find that many good quality performances, including of pieces in this book, are also available freely on the Internet.

What key is the piece in?

Are there are any modulations to other keys, if so what are they?

What is the main rhythm of the piece?

Are there any variations on this rhythm?

If you designate each section with a letter such as A, B, C, D etc, What is the form/structure of the piece ? Note which sections repeat.

Try to sing the piece before playing it or as many sections of it as you can sight read. This should help you play it better later, and help develop your sight reading.

Try to play the entire piece including repeats - slowly. If you make a mistake, do not stop or go back to the beginning, but just keep going as best you can. The idea here is to get a sense of the flow of the piece.

Practice segments where you have to move from one section to the other. Practice the turns to sections that have to be repeated.

Try to vary the order of playing, so that you gain a different understanding of the structure of the piece, and you don’t simply learn to play it in a mechanical way from beginning to end. For example practice the last section in this way.

play the last bar of the section.

play the last two bars.

play the last three bars.

and so on, adding one or two bars each time

play the entire section.

A difficult or uneven rhythm can be practiced by ignoring the melody element (so as to concentrate on the rhythm).

In a similar way sections which are more difficult to play since they require finger shifts can be practiced at first by ignoring the rhythmic element, and just playing the notes slowly and in any rhythm so as to work out the finger positions.

If you are having difficulty with fast notes, try playing the section softer and slower as that requires less energy. Make sure that you choose a speed and volume such that the notes are played cleanly and none are skipped.

Another way to deal with notes that are too fast is too play a shorter segment of these notes at full speed, then gradually expand that segment to include all the notes.

Identify sections that are still difficult. Make sure that you can sing them and hear them correctly even if you can not yet play them cleanly. It is worse to practice the piece incorrectly rather than not practice, since this has to be unlearned later. For these sections that you can understand, but you still find difficult to play, continue to practice them now, or mark them, as you would concentrate on them in later practice.

Play the entire piece again. Listen to what you are playing critically. This will tell you what sections still need to be practiced in another session.

End your practice by improvising in the same scale using ideas, melody fragments and rhythms that you used from playing the piece. Try to expand on some of these ideas, to interpret them differently, or to build on them.

Try to read the piece again and sing it as you did at the beginning of the practice. You should be more successful now at singing it from beginning to end. Think about the piece, and how you could play it differently next time. Next time you will play it, it will be a different interpretation and never identical to what you played in the past, but how you think about the piece outside and during practice, is the key to a more interesting or rewarding interpretation. Once you played and struggled with the piece few times, it is more rewarding to hear a recording of it, and see how other musicians interpreted the same music.

At some stage, a decision point has to be made whether to continue practicing the same piece, or to move to another one. Moving too quickly between pieces means that we never learn anything deeply enough, but then again lingering on the same piece forever until every difficulty is overcome can be quite boring and unproductive. It is alright to move on, as long as you return to the piece one day, provided it is one that you enjoy.

Silence is an important part of music.

Silence can never sound wrong or out of tune.

Notes on the oud can sometime generate unintended silence as they die or fade away quickly. It is possible to sustain notes through the use of tremolos, or to fill in the silence by elaborating on a sparse sequence of notes. We should not however do this too often, as silence is usually part of the piece, and a characteristic of an un-sustaining instrument, and should be experienced.

We tend to be more concerned about silence, and attempt more to do away with it, when there is something else that is wrong and need to be corrected, for example when the instrument is not tuned properly so it does not resonate, or when our playing is rushed, and we are not listening carefully to what we play.

During improvisation, silence may be used to raise tension. The tension depends on what precedes silence, for example silence is more tense if the preceding notes indicate a dramatic mode shift, or if there is a build up towards a climax.

A relatively long silence in a piece can be an indication of an important change, such as a key modulation or a change of rhythm.

A single note must still sound satisfying, which brings up questions of tuning, and how the plectrum is held and played against the strings, and the tone quality of the instrument being played. If the sound of each string and each tone is not fulfilling, no combination of tones will be.

Use a chromatic tuner (not a guitar tuner). It will help greatly, particularly during the early learning stages. Select a tuner that emits an audible tone as well as a visual indicator of pitch. An ability to alter the pitch from the standard A=440 is also useful.

A practice should start with tuning the instrument. Try not to rush this part, although you might be excited to play or learn a particular piece. Avoid playing an out of tune oud, since the deficient sound will leave a negative impression and memory of the practice, and diminish your interest in playing.

When tuning all strings on the oud using the chromatic tuner, try to also use the emitted sound as the target, and not rely completely on the visual indicator. This will strengthen your hearing ability which is an essential part of music learning, and will reduce your dependence on the chromatic tuner in the future.

When you are not using a chromatic tuner, but you are tuning a string relative to another string, try to imagine what the sound of the string should be relative to the reference sound, and aim to reach this sound. This is easiest when the reference string is in unison or an octave apart. The interval of fourth is also very important to learn and remember on the oud, since most open strings are tuned a fourth apart. Sing the reference sound, then the expected target sound and try to reach this target sound by tuning the strings up.

This may be counter intuitive, but it is actually easier to loosen the pegs on a string and try to tune up again, when we are having difficulty, than to do tiny adjustments. This is particularly true when tuning the two strings of the same course in unison.

The unison tuning of the course strings presents special difficulties, that are not easy to overcome, even when we use a chromatic tuner. An important point to remember here is what my oud teacher used to tell me, that they are two strings and not one. The point is that they should sound good together, and not sound as one string. In fact two strings which are completely identically tuned might produce a thin sound, which is acceptable, but is not interesting or full.

The chromatic tuner uses tempered tuning. This would produce acceptable results, especially when we are in the initial learning stages. Advanced violin and oud players however know, that better resonance can be achieved by using harmonic tunings on fretless instruments. The point to remember at this stage is not to be afraid to deviate slightly from what a chromatic tuner indicates if you actually think it sounds better. Let your ears be the judge.

When tuning by ear, tuning by fourth across the strings (i.e tuning each string to the its neighboring string) is an easy tuning method, but it actually compounds any errors. Using the same reference point of one string to tune all other strings is ideal, but is difficult to put into practice. The usual procedure is a combination of the two.

Using the visual indicator dials of a chromatic tuner to check the tuning is more rewarding than relying on it completely to do the tuning for us. If that is difficult because the instrument has fallen badly out of tune, or when we replace the strings and they are very unsettled, or the learner is at the beginner stage, then it is best to use the emitted sounds of the chromatic tuner to help us with tuning by ear.

If you are like me, you will notice that your ability to tune the instrument fluctuates quite a lot from one day to the next. It must do with with our temperament on the day, whether we are relaxed or stressed, or rushed. The oud is also affected by the weather and humidity, so is less responsive on some days. It may be best on some days, when the instrument would just not sound good no matter what we do, to leave it and come back to it later, when we are calmer.

Learning to tune the oud by ear can take a long time, particularly if you are again like me, and have not played a musical instrument previously. It is lucky for us that chromatic tuners make tuning possible even when we have such difficulties. Your ability to tune the instrument well will improve with time, but accept that it will take a long time to become confident that you can tune an out of tune instrument using only a reference point and by ear alone.

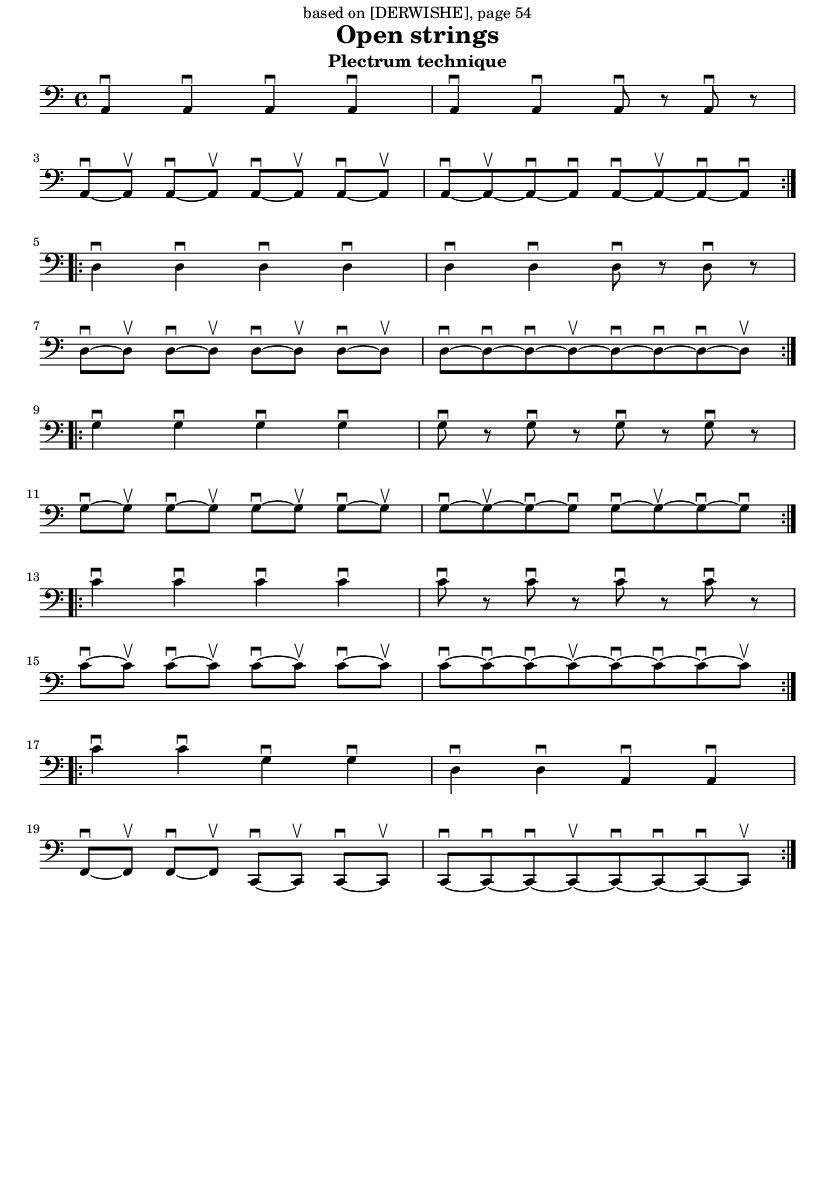

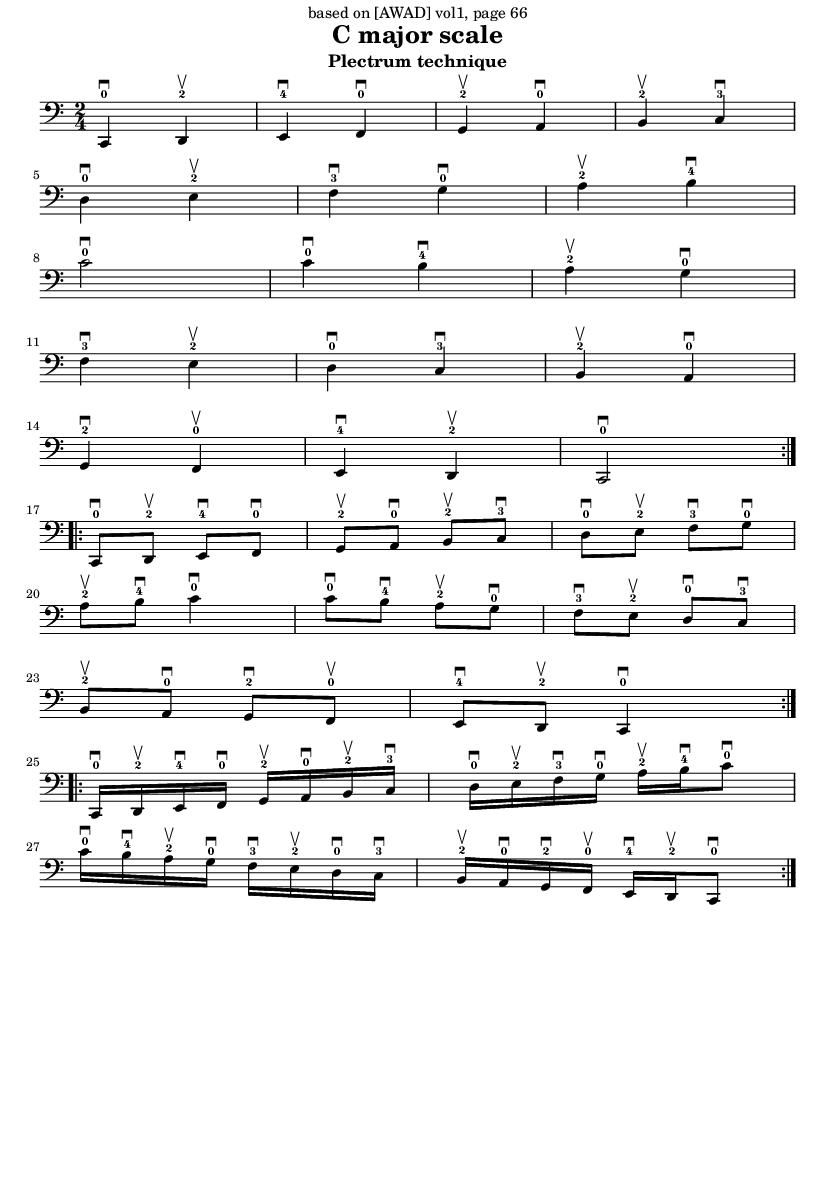

The plectrum must be held and used in such a way as to engage both strings without frequently hitting the wooden surface of the instrument. To do this a circular plectrum motion is ideal, but this has to be interrupted so that there are more down strokes than up strokes. There are many exercises on this in later chapters of this book.

Variations of dynamics alter the nature and expressions of individual notes. Often the dynamics are not marked in Arabic music, and are left to the interpretation of the musician.

Each of the open strings has a different timbre and feel and a different sound universe that can be explored. We need to become acquainted with such variety when we are new to the instrument, and we need to continuously return to simple practices as a reminder of the variety and richness of expressions that are available.

Rhythmic variations are another way to add variety, and this will be more pronounced when melodic and harmonic changes are at a minimum.

Many of the notes played on the oud can be played in more than one position. The notes played on the open string, can also be played on the lower strings (Lower in pitch) in a closed position. The closed note would still have a different sound, even though the pitch is identical to the open note. The closed note has an O vowel sound, while the open note has an A sound. Each string has a different timbre and atmosphere. Each sound will suit a different context.

In general, we try to stay on the same string during a melody, especially if we need only to play on occasional note that is higher in pitch, that is if the transition in pitch is not prolonged to justify moving to a different string. The reason is that such quick transitions between strings can be quite jolting to the ear. There are also other reasons to choose an open string note or a closed note. The open string in the oud is quite powerful and ringing, so it should be used for important notes in the maqam. The open note cannot be wrong if the tuning is accurate. On the other hand, an open note is risky if the tuning is off, since it cannot be adjusted by finger positioning.

Many closed notes also have closed notes that are equivalent in pitch on a lower string, which can be played further up on the fingerboard. Both of these closed notes produce an O sound, so the difference between two closed notes is less pronounced than the difference between an open and a closed note. There is still a definite difference in timber and character which will push us towards choosing one note in a given playing position. Also selecting a given note may simply be more convenient because it will cause us to make smaller and more accurate shifts. A note in a higher position may actually sometimes be easier to play than the one in the lower and more traditional position, depending on the musical phrase. In general, we don’t want to always stay in the first position as this does not cause us to explore the different timbres and characters of an instrument. The instrument is like a world that is calling for us to explore it, so we don’t want to permanently set up camp in one village or town or city. We need to move across the entire surface of the oud, exploring every sound, but learning to do this of course takes a long time.

Playing a note repeatedly can also be made more interesting by varying the key strokes: down down, down up, down up down up and so on. The tremolo technique where notes are played up and down at high speed, is one of the more important techniques to master on the oud. Traditional Arabic music is based on vocal forms where the note needs to be held, yet the notes of the oud, which is the main instrument of Arabic music composition, tend to die away if played with simple strokes. The tremolo technique is beautiful if mastered and used sparingly. Judicious use is the key, because there are other ways to add variety than continuous tremolo.

Pedal notes can also function as a way of emphasizing the mode. The use of pedal notes is of course not unique to Arabic music. See for example Bach’s spiritual and inspiring suite II in D minor - Prelude for cello (BVW 1008) which is full of such pedal and focal points.

Transposition means moving a group of pitches up and down by a constant interval. This preserves the contour of the music, and the distances between the notes. On the oud, it simply means choosing a different starting position for the melody. Transposition by fourth (For example, starting the melody on the open A string rather than the open D string) is usually easy provided the notes are still in the range of the instrument, and can be done automatically when playing as the finger positions are usually the same. On the other hand, some other transpositions would be very difficult or almost impossible to play. Unlike the piano for example where a transposition does not make the music any easier or harder, the oud is an instrument of limited transposition, and the same generalization can be made about Arabic music in general. The reason for this is that some transpositions would lead to too many sharps and flats which means that the ringing open strings are not used, and some notes are difficult to reach. Many of the Arabic maqams are started in a few limited positions. For example maqam Rast is started on C or sometimes D or A or G but almost never on C#.

There are many reasons why transposition can be useful for us as players and composers that are exploring the instrument. The first is choosing a position that will make the melody playable. That usually means that at least some of the notes will fall on open strings, and there are not too many dramatic or sudden finger or string shifts. Another reason, is that although the melody is the same, we may feel that a mellower sound may suit its character more, so we try it in a lower key, or the opposite may be true. We may also transpose the piece when we are playing with others, or accompanying a singer, which can be easier and quicker than having to re-tune the instrument up or down. Transposition is also a valuable practice and learning mechanism, which we can use to gain more understanding of a melody or a scale, by looking at it from different angles.

When we first learn the oud, we learn to play with simple down strokes. This helps us focus on the rhythm as we practice playing the open strings in our first lessons. Soon afterwards we focus on the left hand technique as we struggle to learn the correct intonation and left finger positions to produce the sound of the various Arabic modes.

With all the focus on the left hand, the right hand plectrum technique tends to get left behind, but it is really the right hand technique that produces interesting and engaging oud playing. Playing with a simple plectrum technique can produce nice and accurate sounding Arabic music if all other elements are right, but it is never engaging enough particularly in solo playing. It is like a meal where all the important ingredients are present, but which does not have any added spices.

Even continuous down strokes can produce a more interesting sound if the hand movement is more circular so that both strings of a course are engaged on the way down, and the hand returns to the initial position to repeat the stroke. In faster passages, however, there is not enough time to complete this movement and play all notes in time, so we play a note on the way up as well.

For instrumental pieces where the music is quite busy and full of shorter notes, and for certain playing styles such as the Turkish or Iraqi styles which focus on instrumental oud pieces, alternate up and down strokes is a good technique.

Other oud playing styles such as Palestinian, Lebanese, Syrian and Egyptian reflect more the rhythm and melody of traditional Arab songs where long sustained notes and a strong rhythm are dominant elements. This presents different challenges in playing an instrument where notes die as soon as they are plucked and where the sound is soft even when compared with other traditional Arabic instruments such as the kanun or the violin.

Faced with such a challenge, the use of tremolo to produce more sustained notes is quite common, and it is also common to give a preference to down strokes, and use up strokes only when necessary. In particular, down strokes are often used when moving to a new string, or for longer notes. Up strokes are limited to short notes such as sixteenth notes when no string transition is necessary. In this case the up stroke gets the string vibrating in an opposite direction making the following down stroke even more effective. In such a playing style subsequent down strokes are quite common.

This style of playing takes account of our natural strengths where our down strokes often feel stronger and more comfortable despite all the practice that we need to do to improve and balance the strength of our up strokes.

Also in such a playing style, longer notes such as quarter notes or half notes are often not played exactly as written. If the note is not long enough for a tremolo then it maybe doubled or quadrupled or embellished in some way. This keeps the music moving particularly in solo playing unless silence is really intended.

So the resulting music with this emphasis on down strokes will have a plectrum pattern that is more like: down-up-down-down-up-down etc. where the ratio of down strokes to up strokes is roughly 2 to 1. This varies a lot of course depending on the piece and the taste of the player.

In Taksim playing, where the rhythmic element is quite free, the possibilities of varied down-up stroke patterns are greater, more individual and more important.

This more assertive playing, which aims for a louder clearer sound, also calls for playing closer to the bridge, the selection of a plectrum that produces a good and clear sound volume, the plectrum approaching the string in a more vertical orientation and with more contact in order to get more sound, and letting the hand fall from a higher position when the music tempo allows enough time. These are all techniques that can be explored and adjusted according to the taste of each player.

It is also often a good idea to slow down the tempo a little and not rush in order to allow enough time for these divisions of notes and plectrum variations to happen. It is also a good idea to introduce variations gradually after the basics of a particular piece of music has been mastered.

The important point in all of this, and in the following exercises, is to pay attention to plectrum technique, to explore its variations, and to be able to control it and vary it.

The other point is that Arabic music notation is only a sketch of how the music should be played and how it should sound like. I added stroke directions to some of the exercises and you can see how more complex the music is, just by adding this one element. This is one reason why, like learning a language, it is impossible to learn such music just by reading books, and we have to be become fully immersed in its sounds in order to learn it.

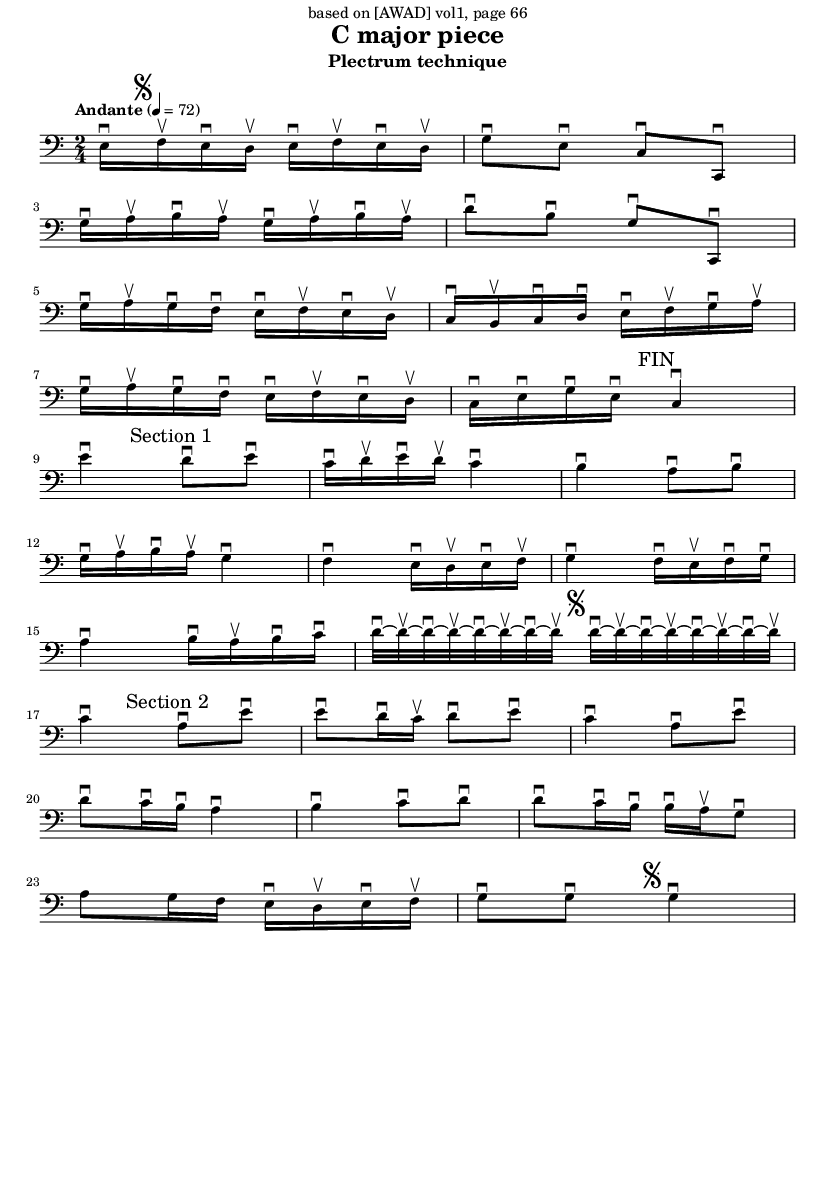

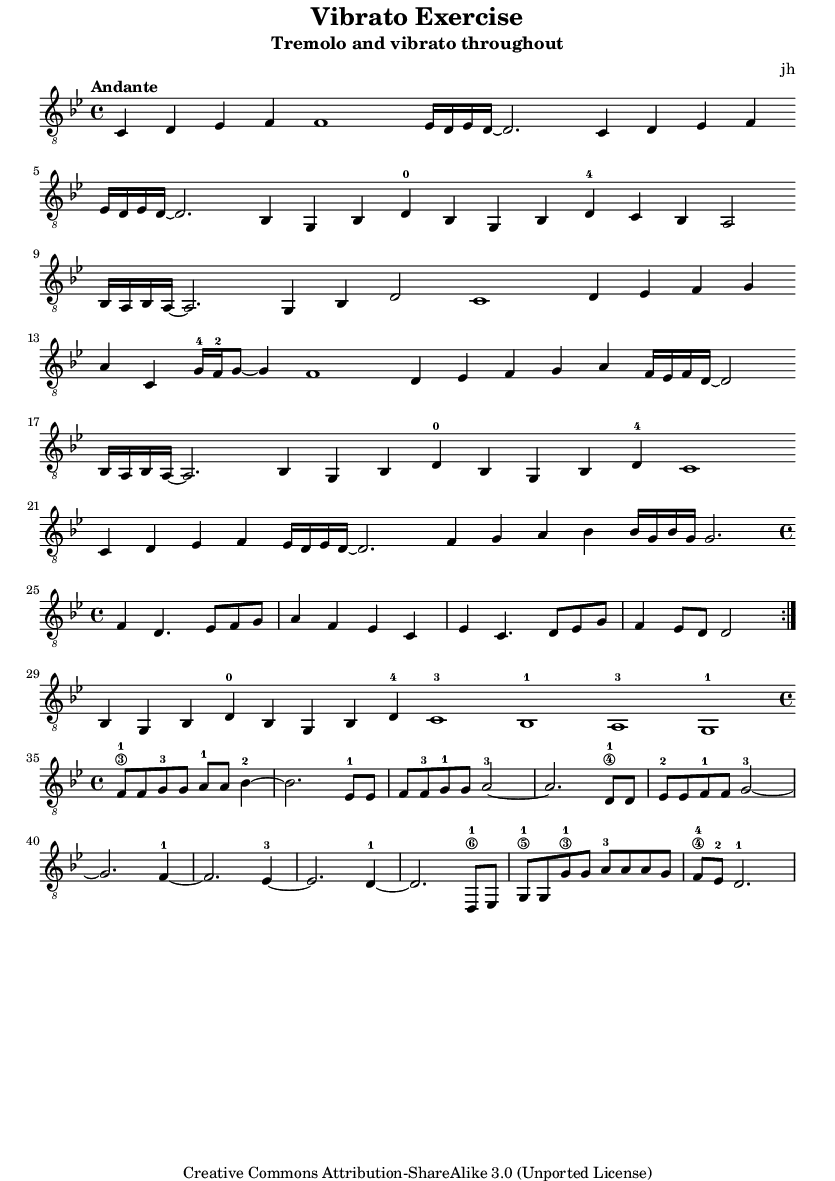

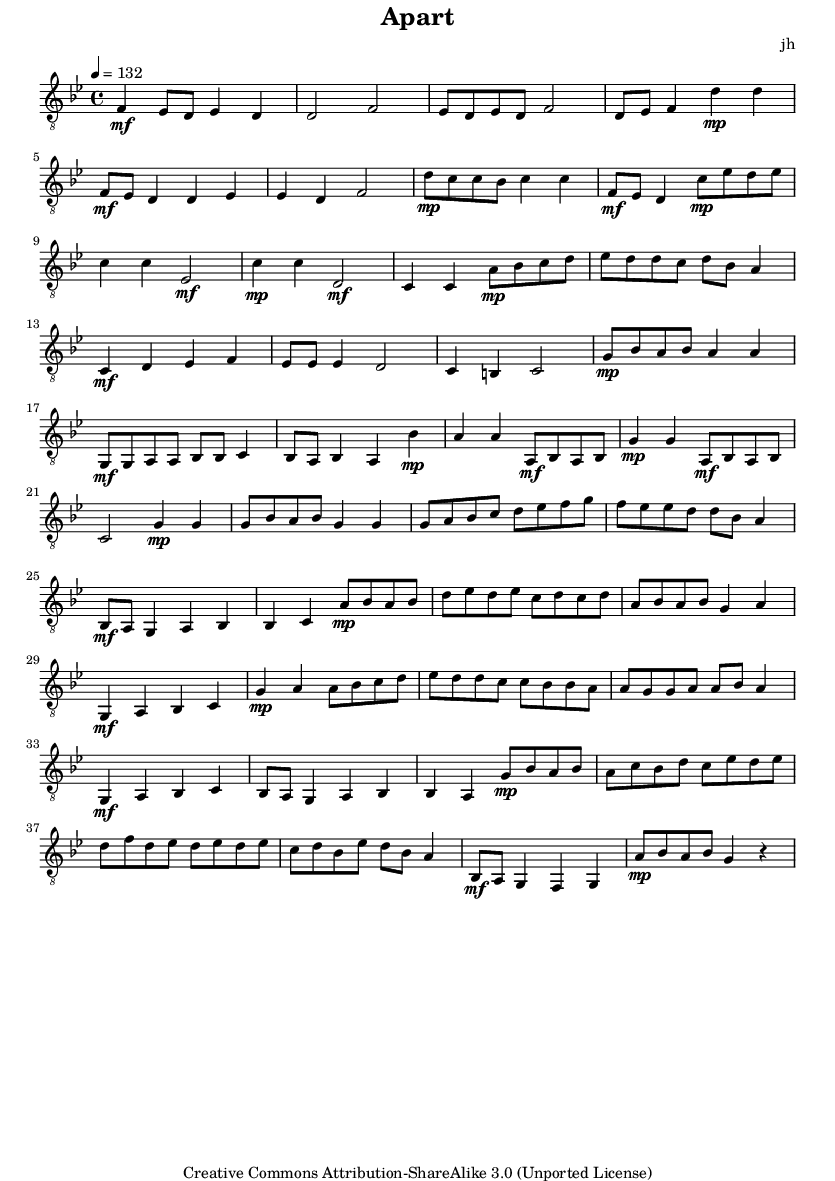

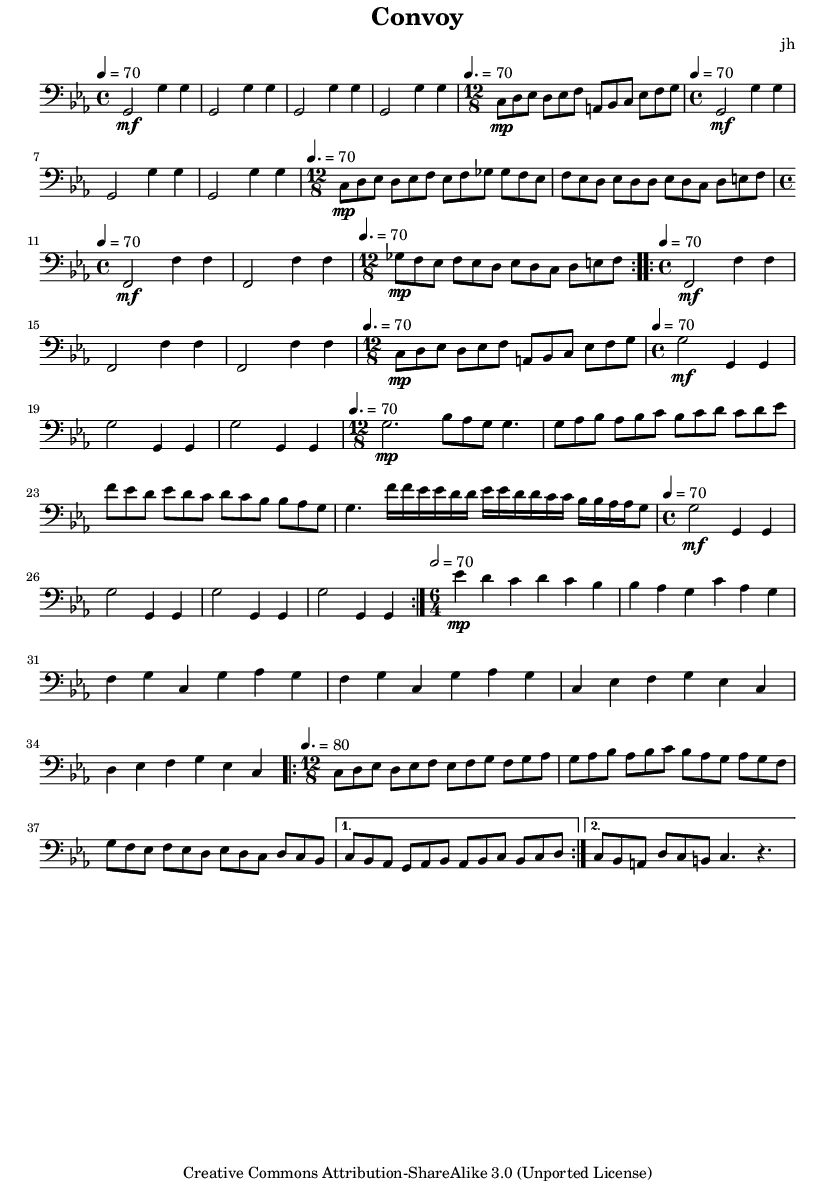

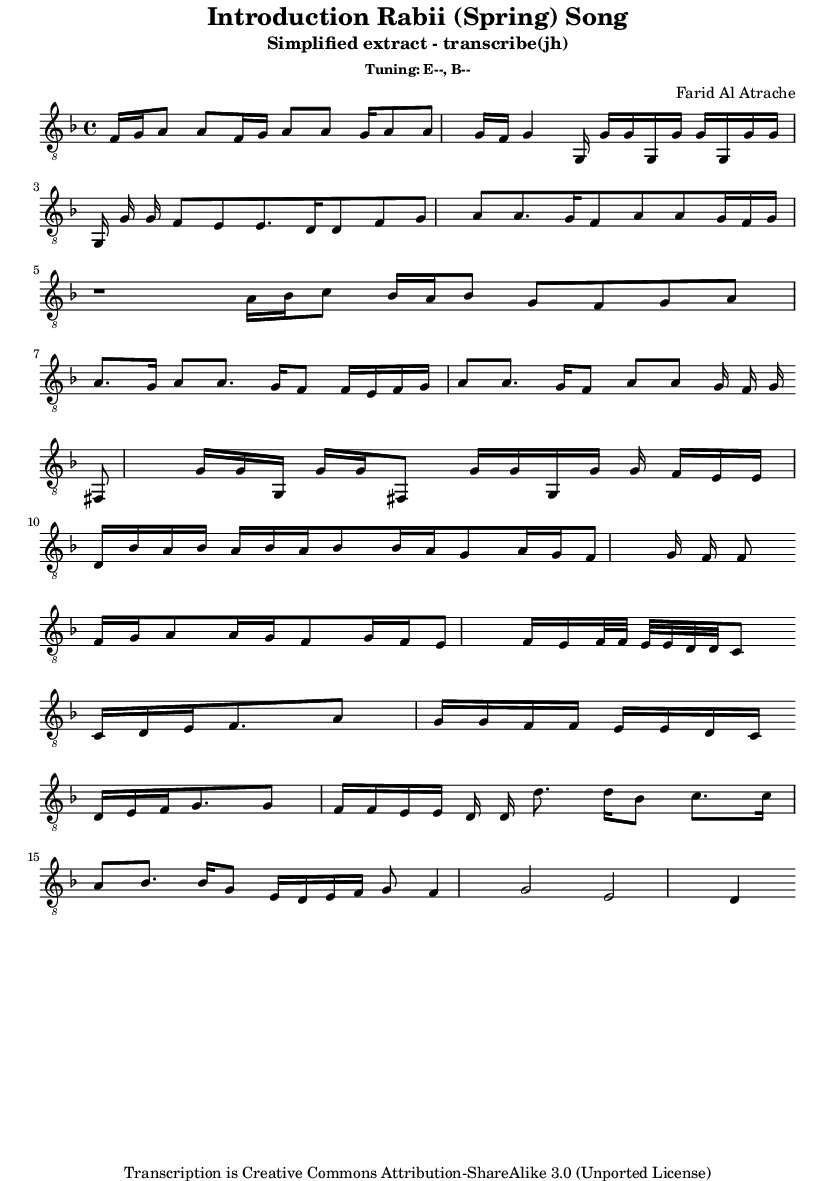

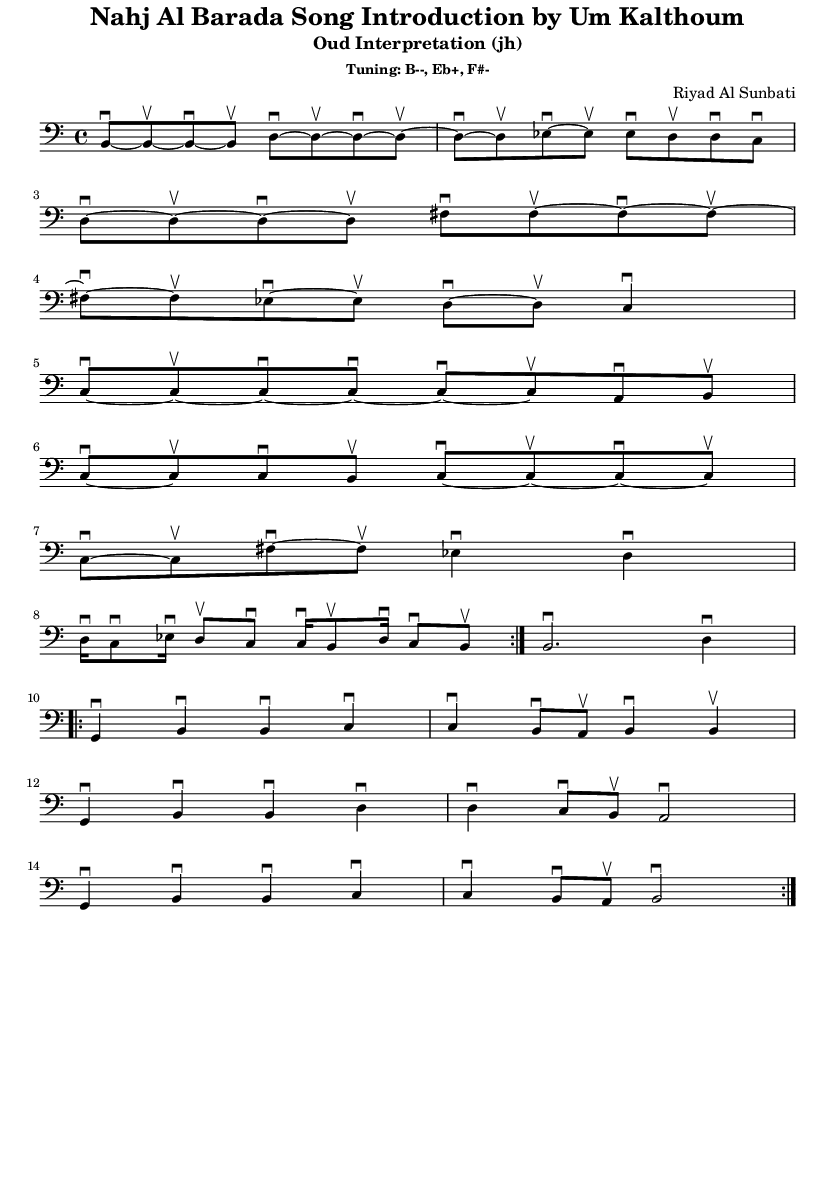

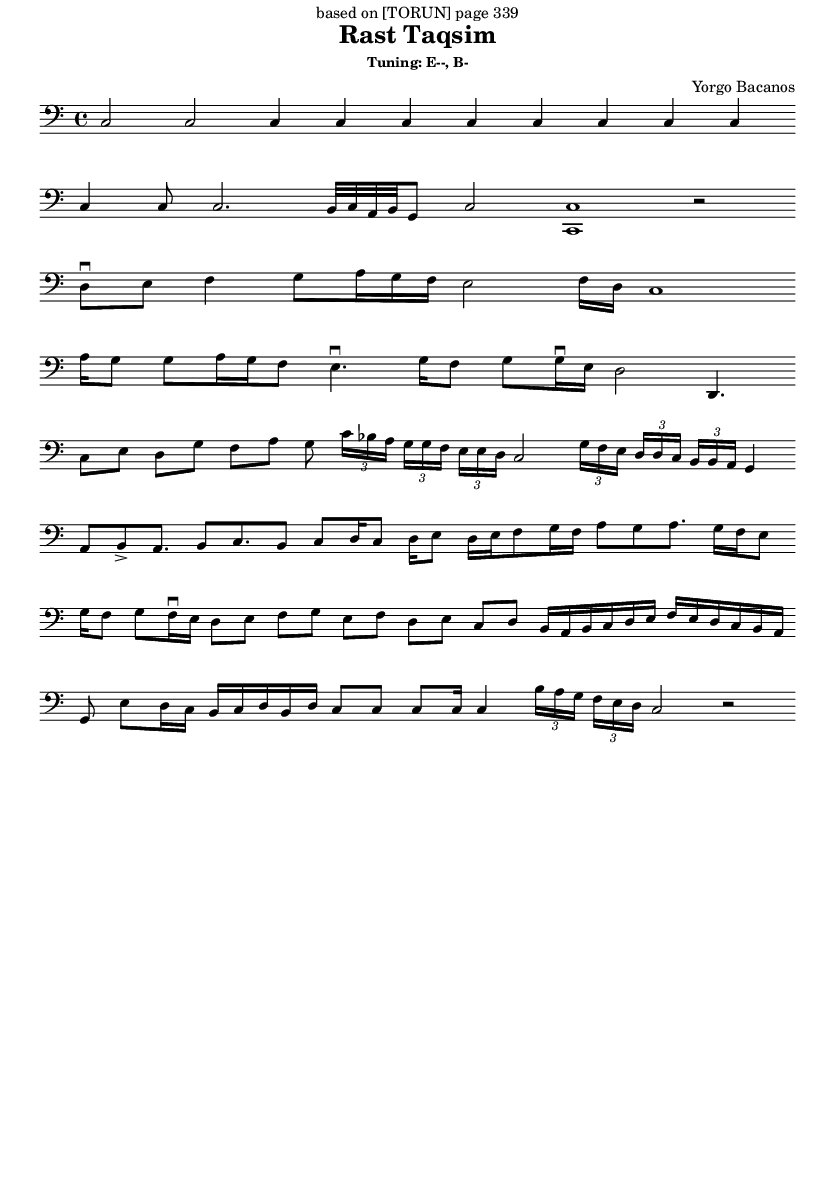

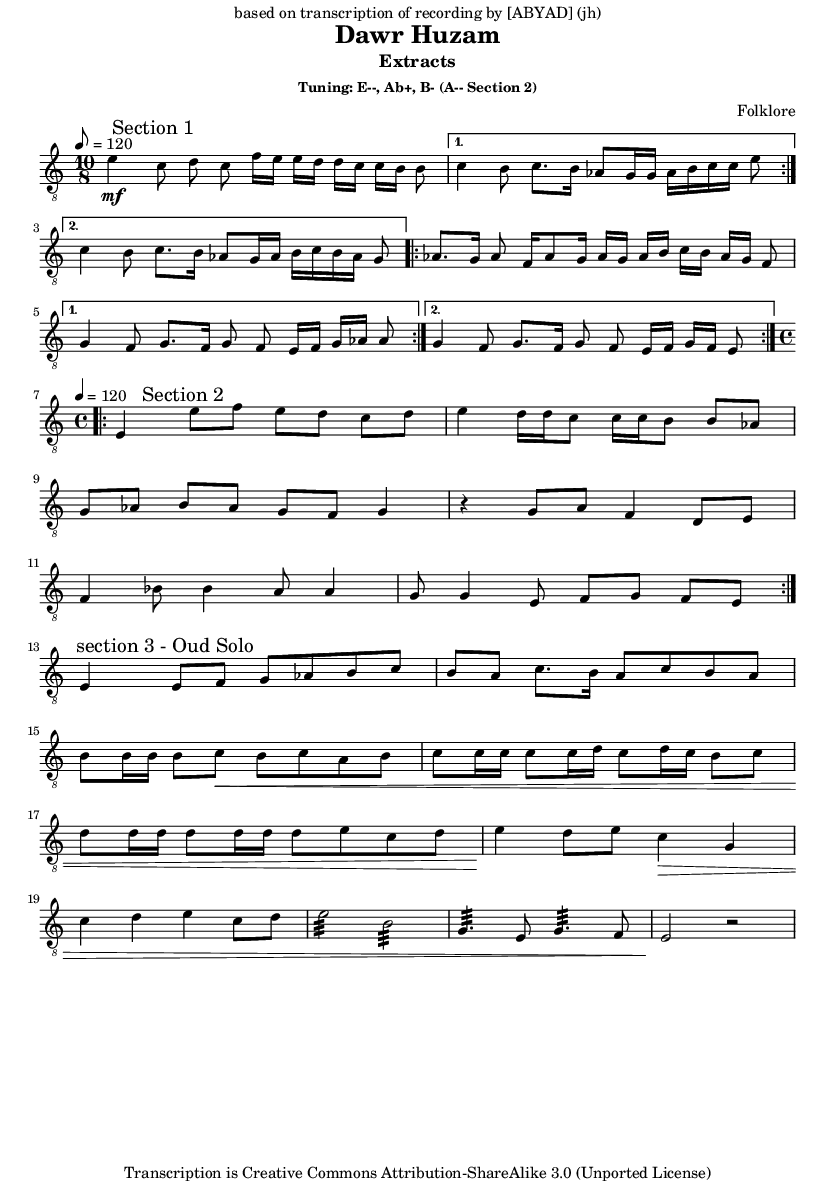

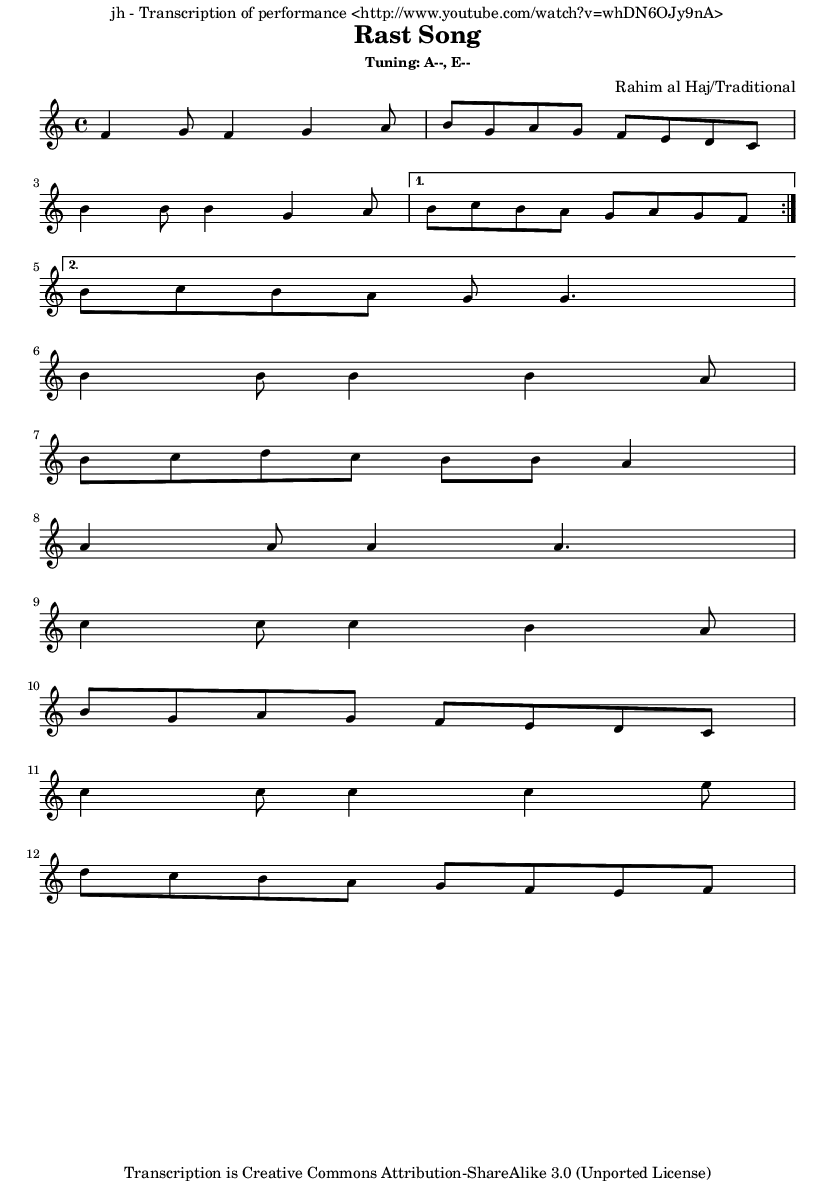

recording using - iphone 7 - 26 February 2021

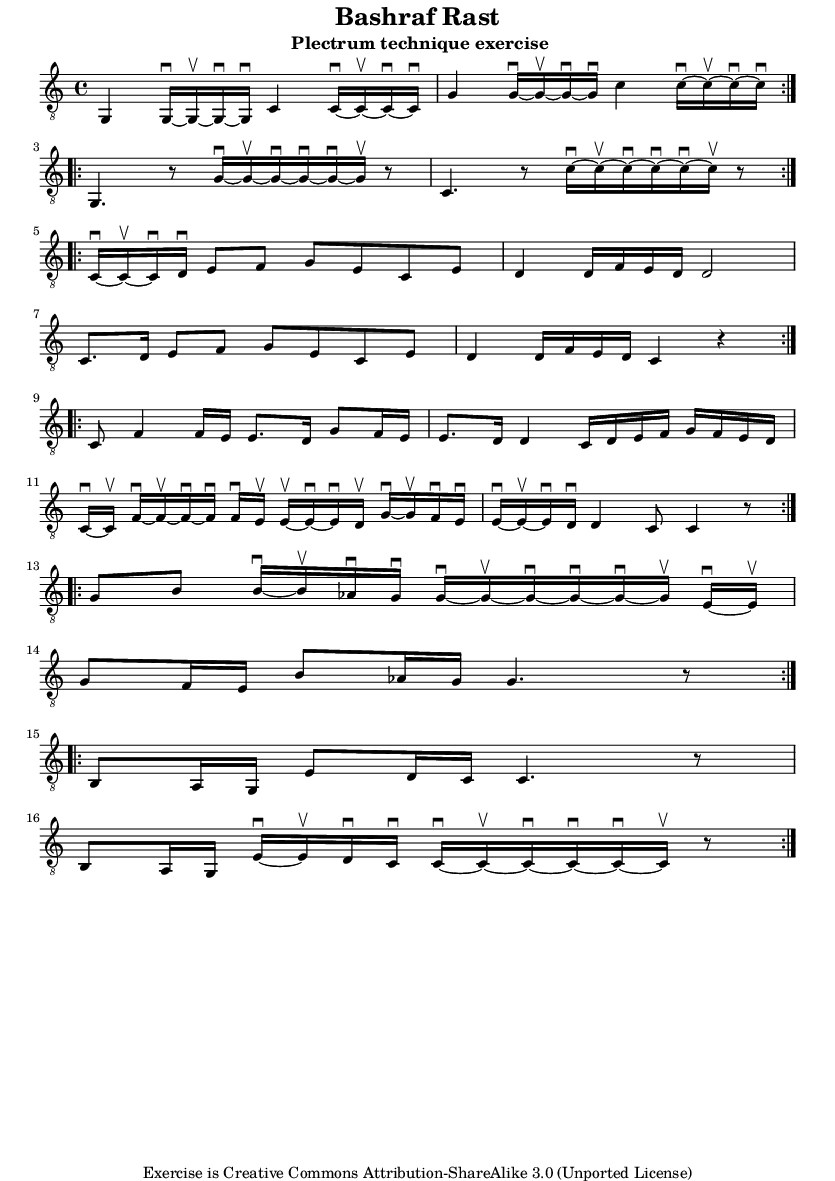

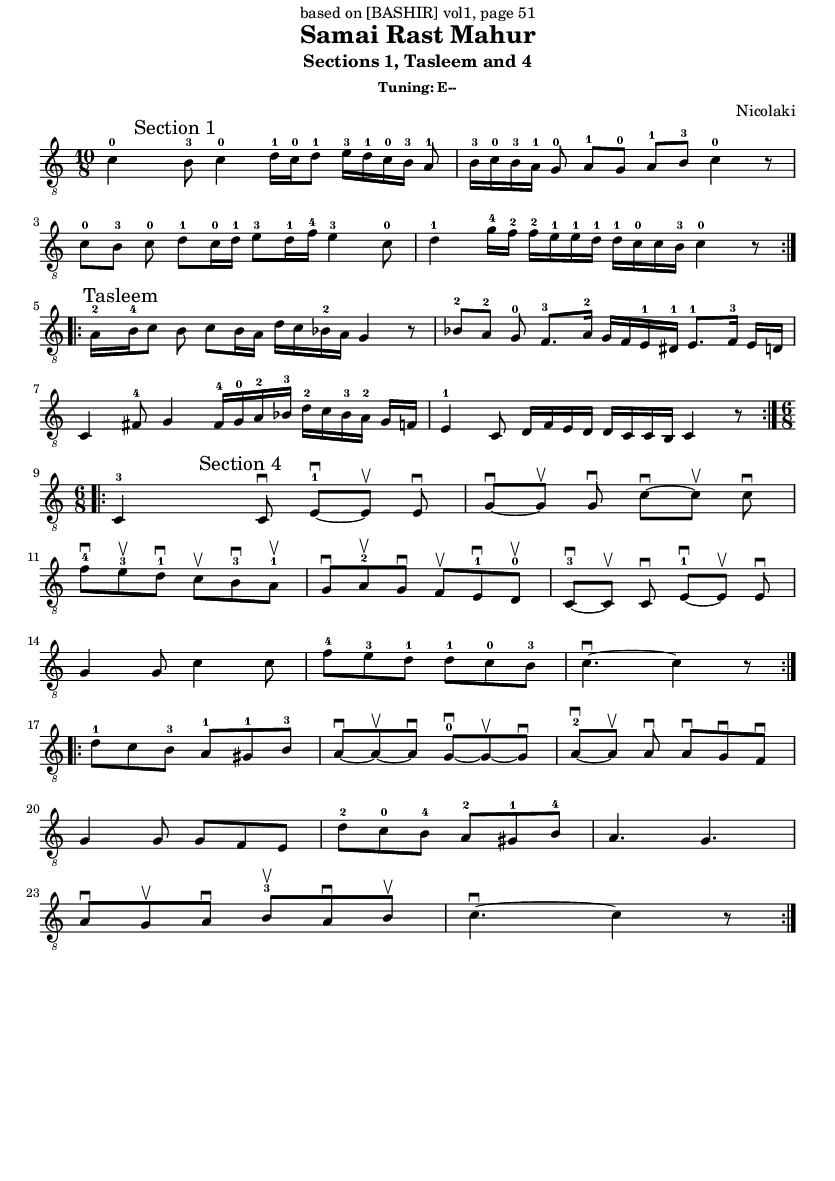

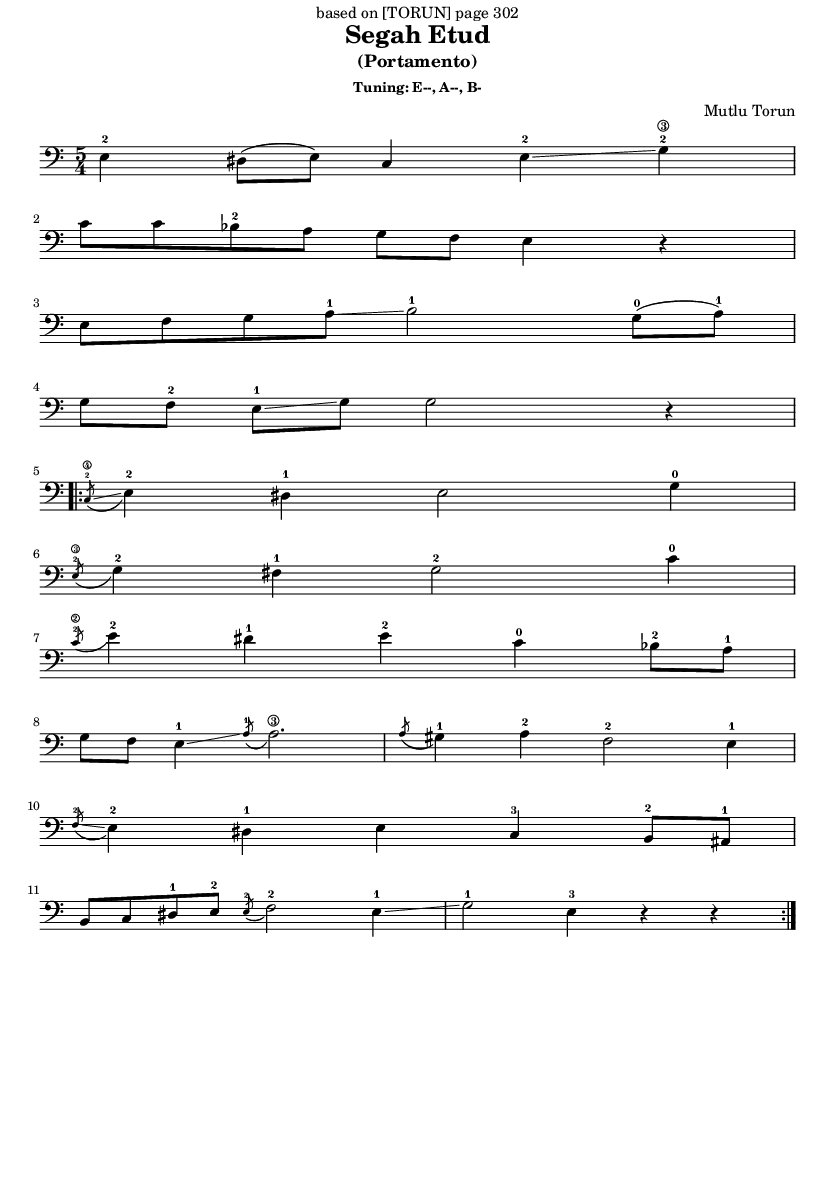

recording using - iphone 7 - 7 March 2021

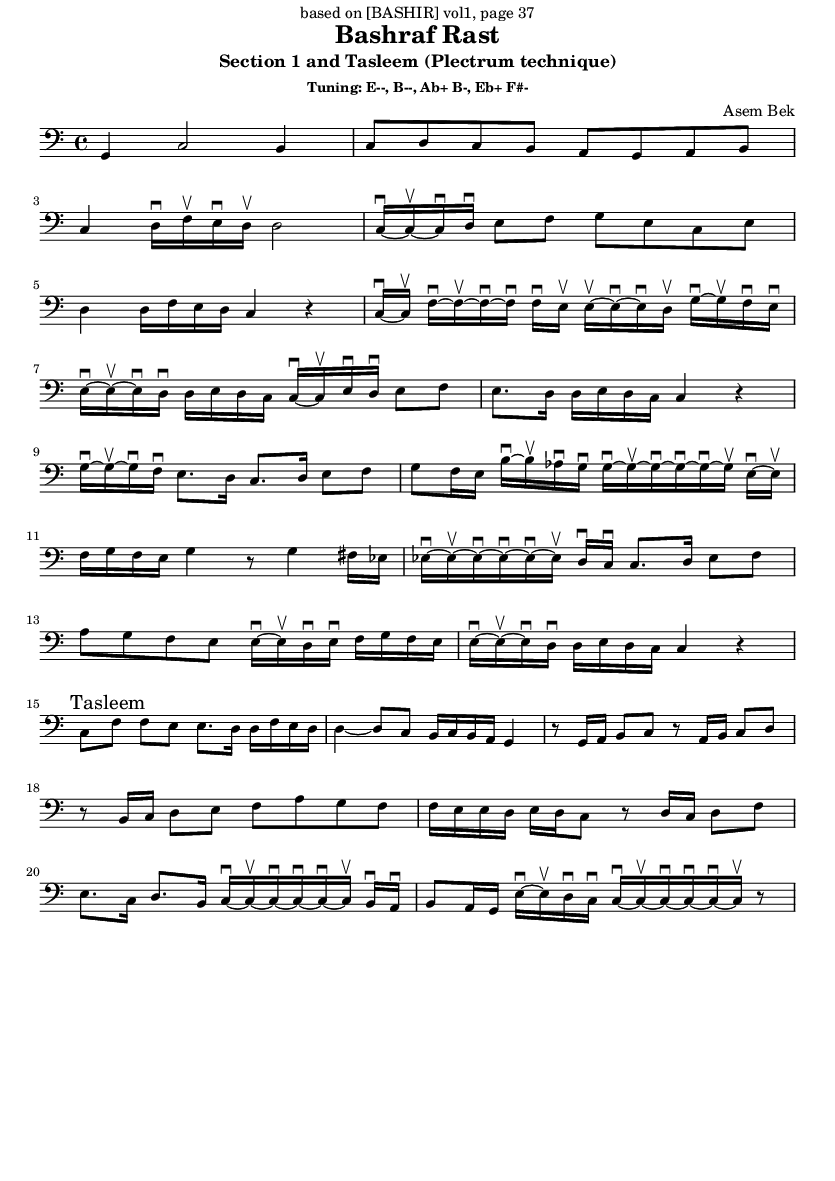

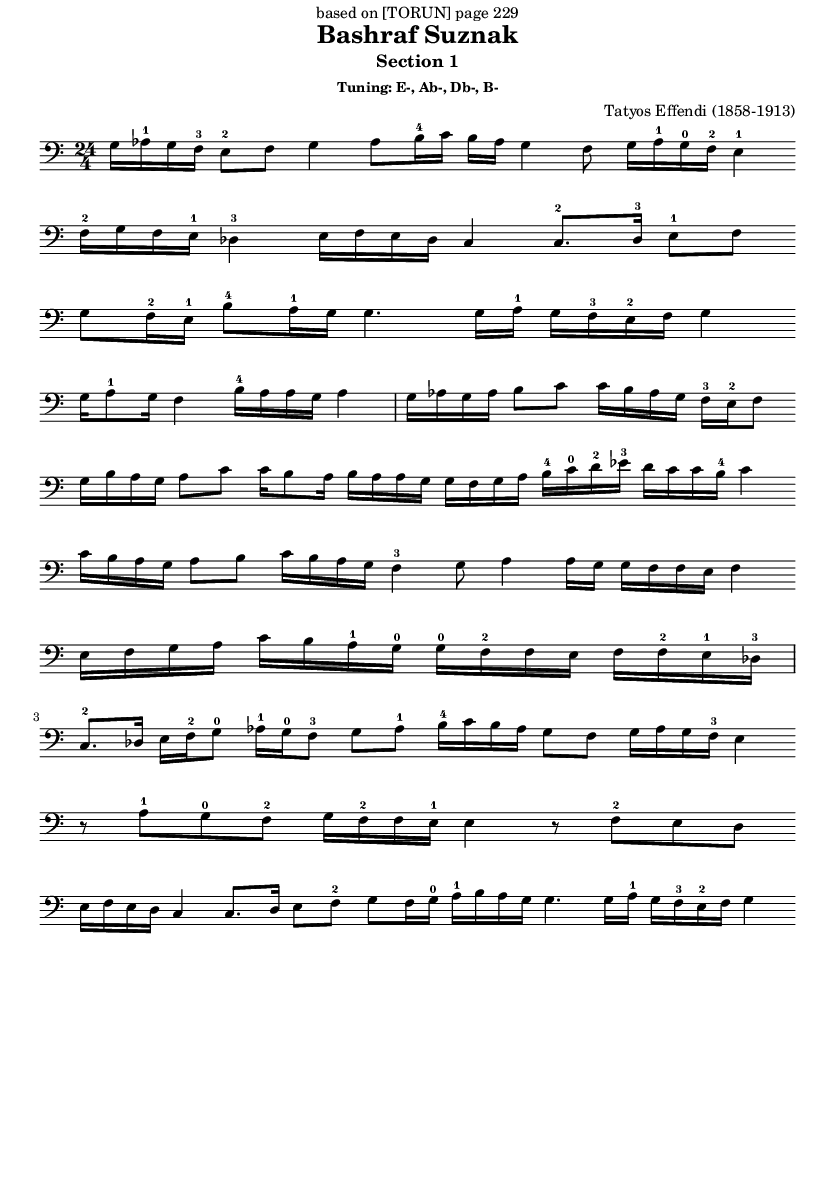

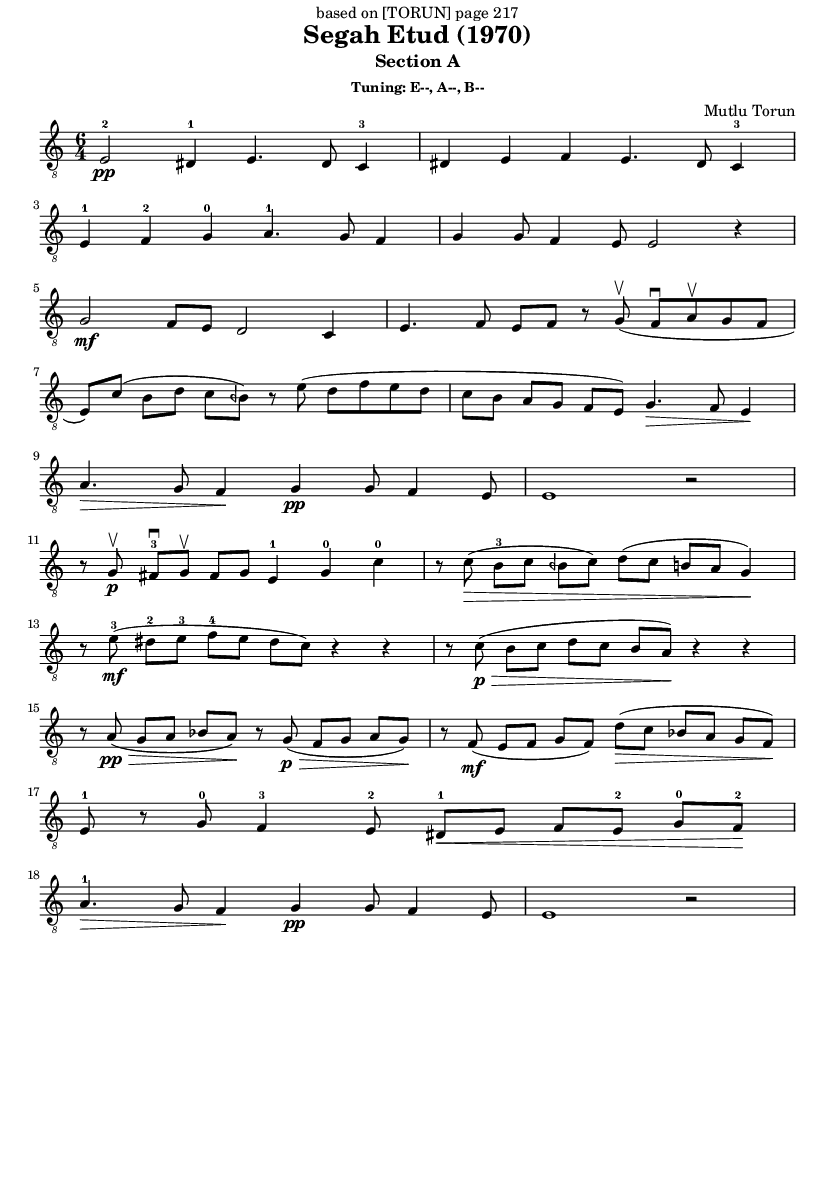

recording using - iphone 7 - 27 October 2022

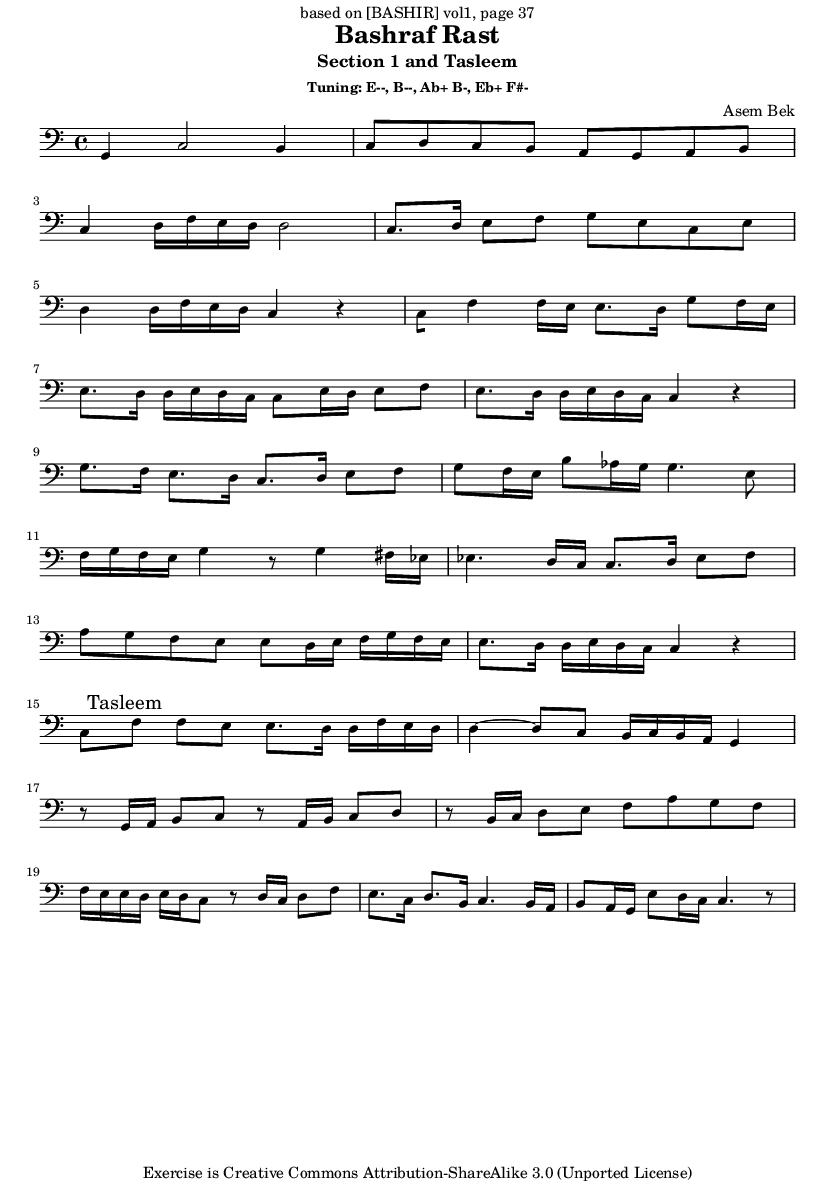

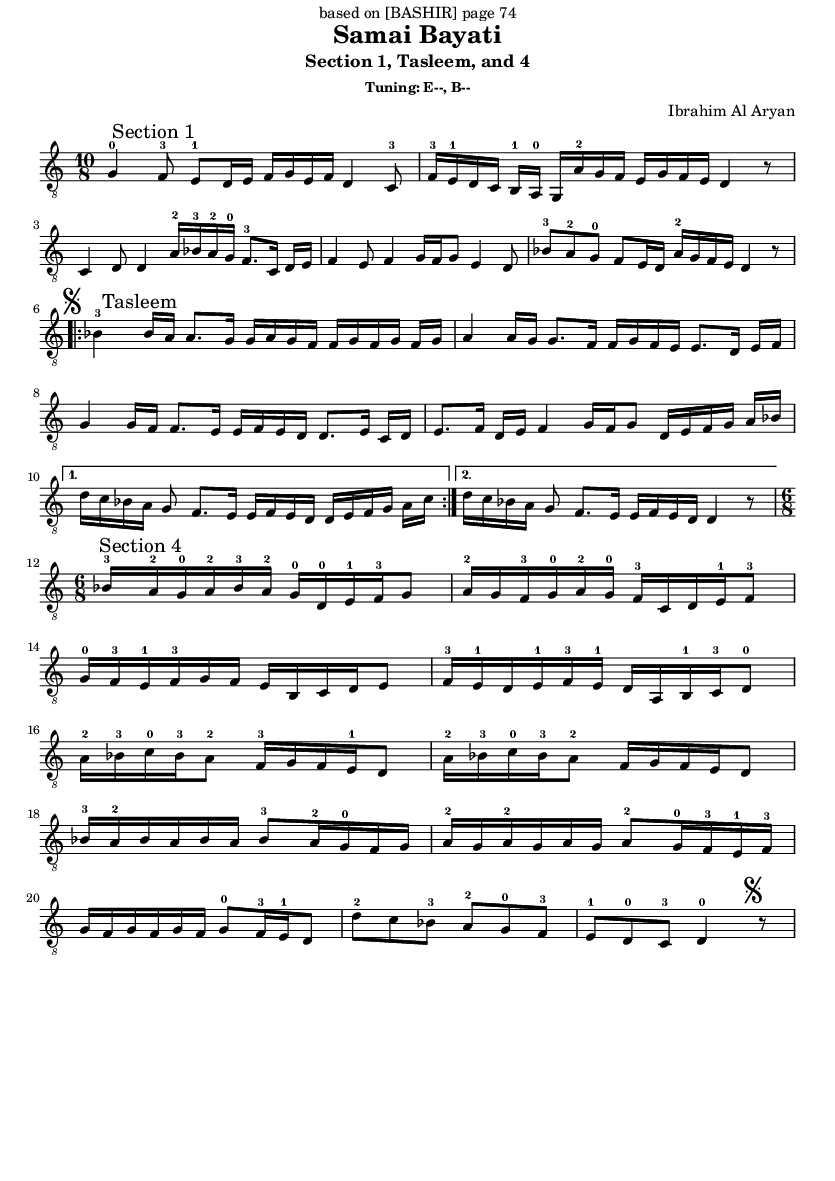

recording on 31 May 2020

recording using - iphone 7 - 25 February 2021

recording on iphone 7 - 24 April 2021

To play the short notes in bar 2, touch the open string with the left hand to dampen the note.

Focus on the different feeling in your right hand as well as the sound difference of alternating down and up strokes compared to subsequent down strokes, for example the contrast between bars 7 and 8.

It takes slightly more effort to play the lower string which is often only played as a drone or to echo important notes of the scale, but the sound in bars 19 and 20 is quite special and as Mr Darwish says in his book - Listen and enjoy.

Notice how a change of string is approached with a down stroke regardless of the previous stroke.

For interest, the ratio of down strokes to total strokes in this piece is 2/3.

Practice slowly bars 1-16 until the plectrum technique is ingrained before advancing to the faster speed of the following bars.

This is the most important exercise of this chapter as it shows how scales can be practiced in a way that suites the instrument. This type of exercise should be practiced frequently and regularly in order to improve the playing style.

Try to play the chord in bar 8 with a mix of up and down strokes. It is harder and does not sound as good, and shows clearly how subsequent down strokes can be a better choice when changing strings.

Bar 16 is just showing the alternating up and down movements of a quick tremolo. It is more important to keep the rhythm of the piece rather than fit in every note as written.

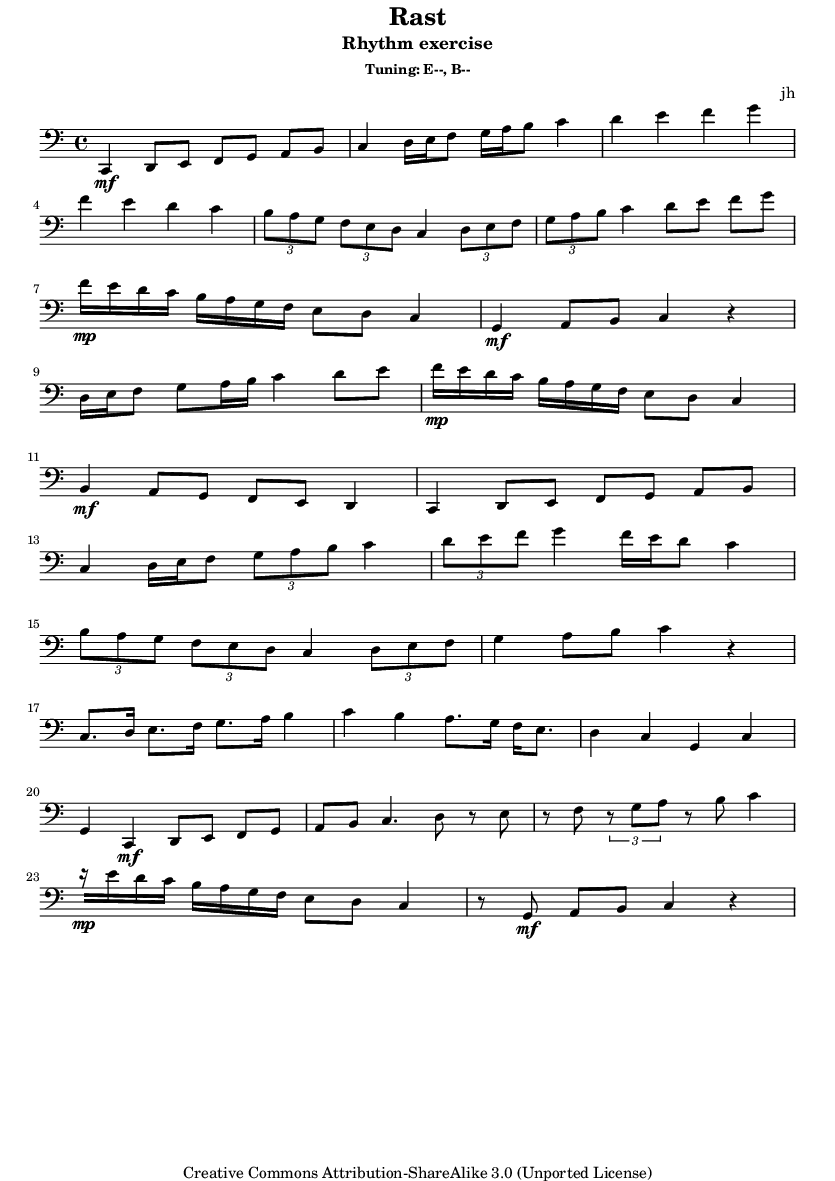

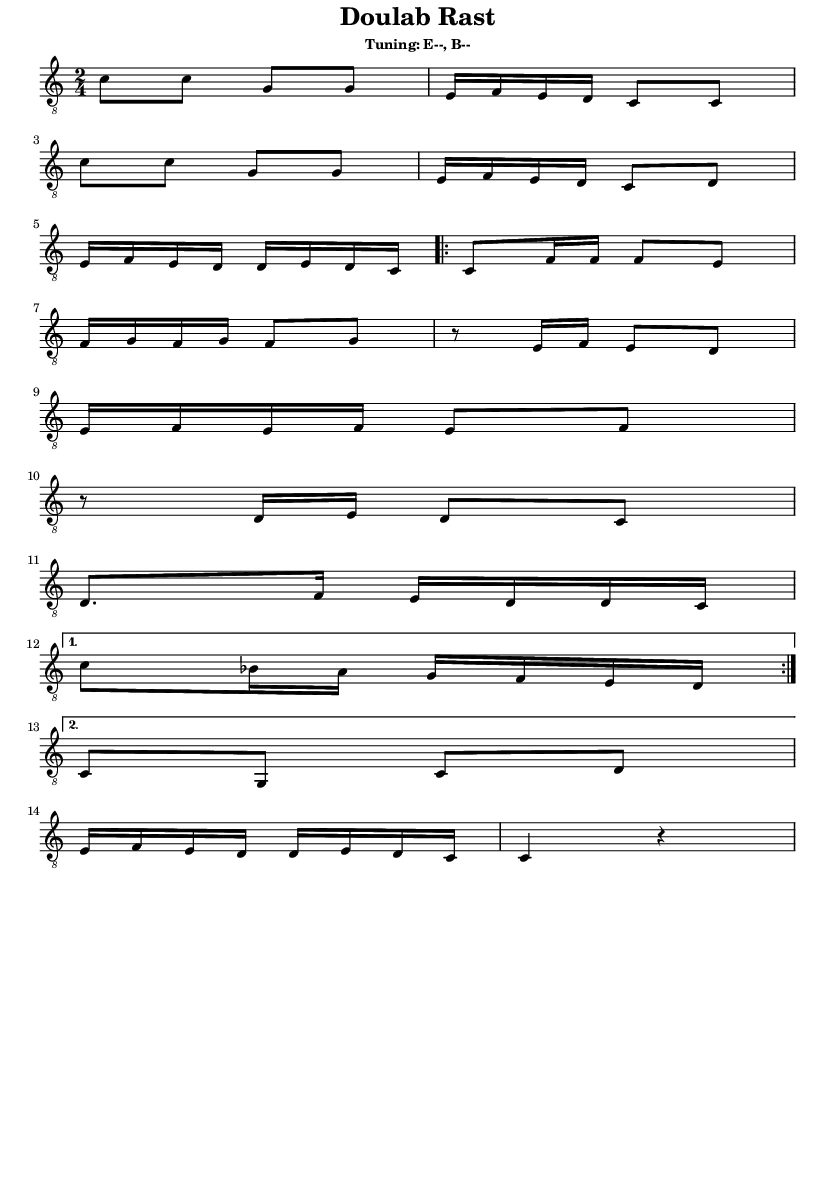

Even with a simple plectrum technique, this piece sounds good when we accurately capture the intonation of the Rast scale, and the rhythmic variations.

Try to listen to this piece. Practice it with a metronome and by tapping your feet. Work on the off rhythm, for example in bars 6, 11 or 17.

Master this piece thoroughly before moving to the subsequent pieces that will add another complexity of plectrum variations to it.

The first four bars simply show how written notes of different length can be played with a more elaborate plectrum technique.

It is only important to follow every plectrum direction for the sake of an exercise and to learn good plectrum control.

Practice with simple and elaborate plectrum technique. The aim is to add these variations without losing the rhythm or feeling of the piece.

This exercise is quite complex. Practice parts of it and return to it occasionally as your plectrum technique improves.

This exercise builds on the previous two exercises to play these two sections with a lot of embellishments.

Arabic music is almost never written with such detail, as the detail is distracting but this is done here to show how a piece can be made more interesting and the notes more sustained by subdividing the notes and varying the plectrum technique.

It is very easy to loose the rhythm and feeling of the piece if so many variations are attempted before the piece is completely mastered and the player is advanced enough to attempt this. In such a case it is better to aim for more correct rhythm and add variations later and gradually.

As for the previous exercise, practice this occasionally and return to it every now and then to test your plectrum technique.

Here the phrase and its embellishment are rendered side by side for easier comparison. Return to the original phrase rhythm if you get lost in the detail.

Try slowing down the music, playing closer to the strings, or focusing on smaller phrases if you are having trouble fitting all the notes in.

Again this is just an exercise. Every rendition of Arabic oud music to such detail is unique and depends on the player.

One of the main problems in playing the oud, one that I struggled with for a long time and I still have to remind myself of, is the tendency to clutch the neck too tightly between the palm and the thumb of the left hand. There is a similarity here to the way we clutch the steering wheel so hard when we first learn to drive. The left hand should only lightly touch the back of the instrument.

One reason for this, besides feeling general tension which can result from various reasons in daily life, is a worry about the instrument slipping while playing, specially when shifting, because of the round shape of the oud. This is particularly true if the instrument is too large for the player. We can mitigate this problem by choosing an instrument of the right size, and also by experimenting with holding the instrument in such a way that it will not easily slip and is not totally supported by the left hand.

Another problem that many of us have to deal with is the weakness of the fourth finger. It is possible, unless playing advanced oud music, to avoid using the fourth finger and use the higher open string and fingered notes in lower positions on that string instead, but that would not always produce the best musical results. It is best to always practice using the four fingers (excluding the thumb), and add special practices for the weaker fourth finger. Naturally, some fingers will always be stronger than others despite sustained practice, so we also have to account of this natural difference in deciding how to play a given piece.

Another problem, which may be a developed habit, or caused perhaps by being tense, is to press too hard on strings. Often, if not caused by tension, this is also due to another problem such as a bad tuning of the instrument, or bad intonation leading us to think than we can correct this with more effort during playing.

This is especially true but totally unnecessary when we play louder, but feel that we also need to press harder to produce a louder sound. If we press hard enough we can even bend the fingers out of shape particularly on the higher string. This can over time damage the fingers and does nothing to improve the sound.

Another problem, which many of us face especially at the beginning stage, is unnecessary hand or finger movement. For example if a short passage requires repeated alterations between the first and the second fingers playing two notes then only the second finger needs to lift, but our initial tendency is to try to lift both. Following this tendency requires more effort and may mean that the passage may not be played cleanly in time.

Another problem, that is particularly common in oud playing, is to be stuck in first position for ever. Some passages are actually easier and may also sound better in higher positions, or when we learn how to shift up and down. Some of the more modern oud book techniques encourage such shifting, but it is a problem for those that learn the oud to accompany vocal music and do not practice much with written instrumental pieces.

So when it comes to the left hand, minimal and lazy is best. Leave the fancy work for the right hand. Aim for round fingers touching the strings with just enough tension to produce the sound and no more. Explore the whole surface of the instrument and do not clutch or hold too tight. Aim for minimalistic and effortless movement.

We can also learn a lot here from violin technique and education which you can find online or in violin books.

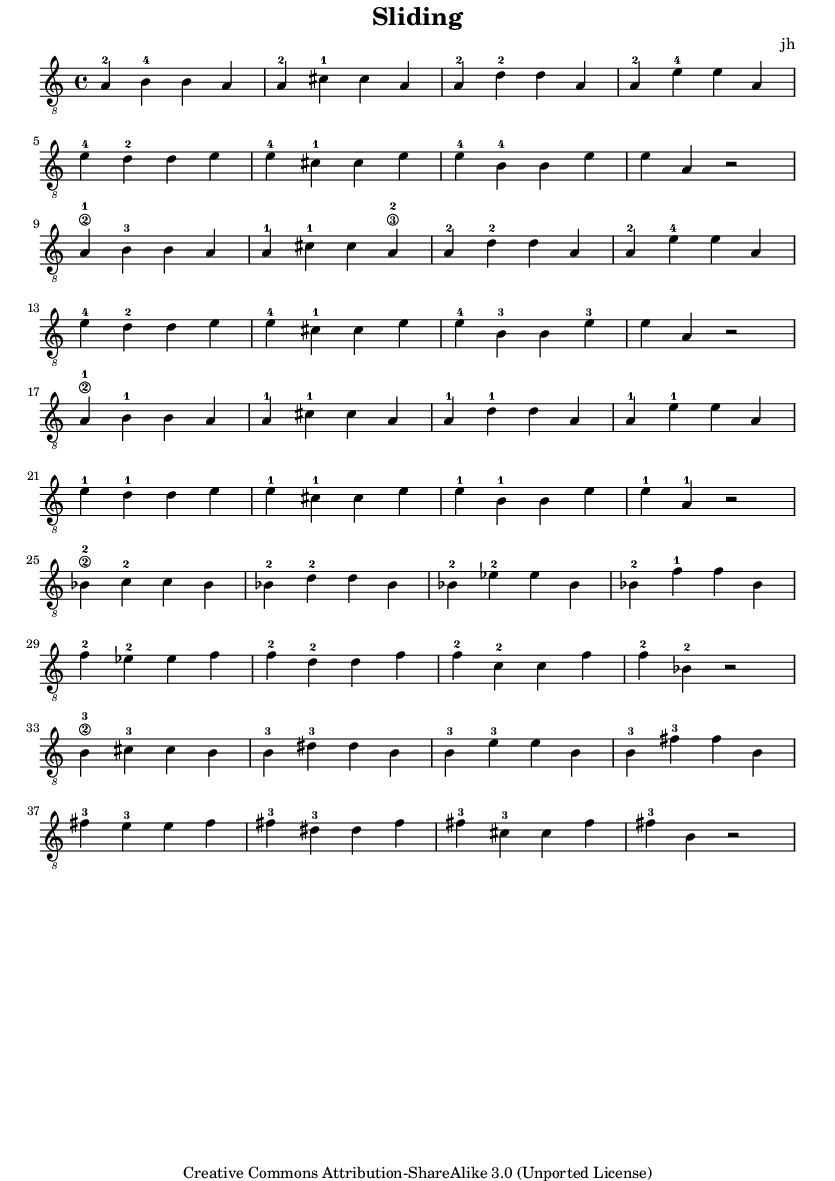

I learned this exercise in my violin/viola group class and it works well for the oud too. It teaches shifting and sliding, and it is also a good exercise to loosen the left hand grip at the beginning of each practice.

Bars 1-8 teaches the melody in first position. It is important to get the intonation of this right and remember the sound, as it would be easier to replicate this sound rather than think about the exact notes when shifting.

Bars 9-16 replay the same melody but a shift on the first finger from A to C# is required in bar 10 and we stay there until bar 15 where we shift down to the original position.

Bars 17-24 replay the melody using only the first finger on the second string and shifting up and down to reach the notes.

Bars 25-32 replay the melody modulated a semi tone up using the second finger on the second string.

Bars 33-40 replay the melody modulated a tone up using the third finger on the second string.

This exercise is a lot easier if we memorize the sound of the various intervals, rather than trying to work out the positions of individual notes.

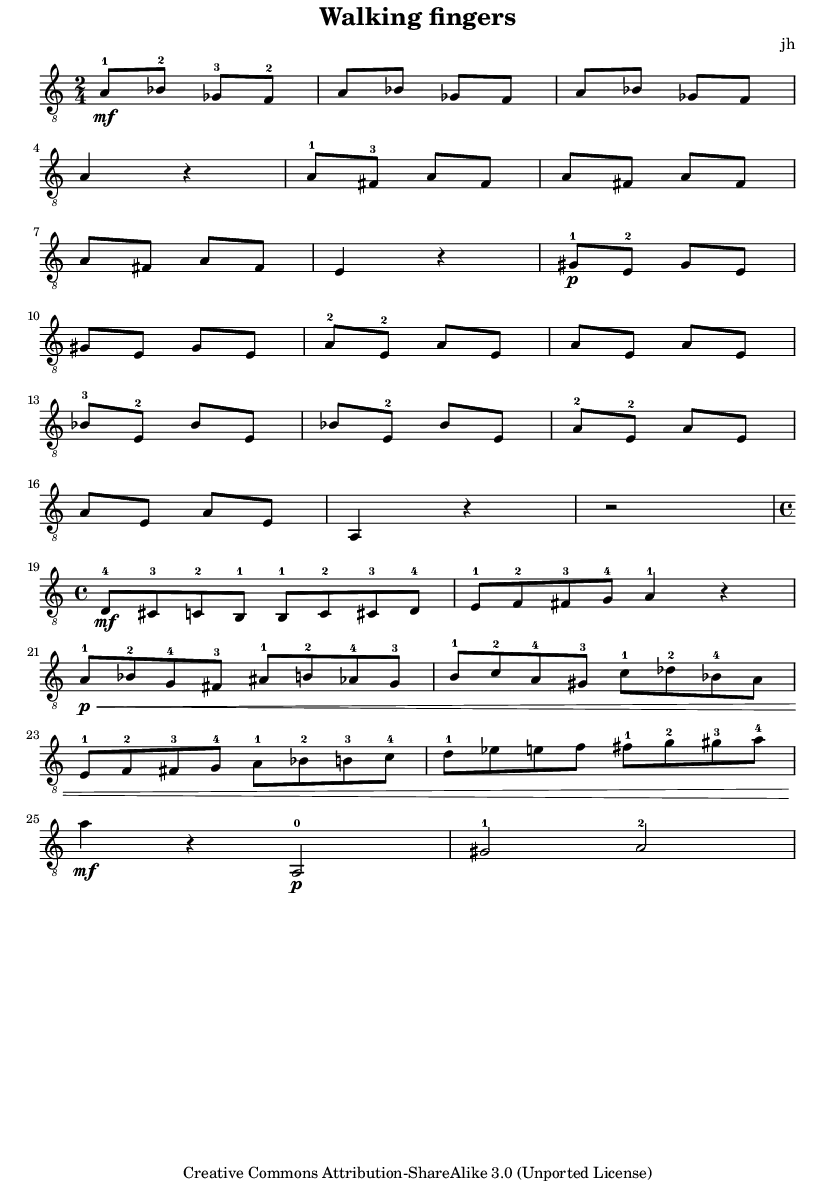

This exercise is designed to practice all fingers, including the fourth fingers, across the strings of the instrument.

In bars 5-8 explore lifting or not lifting the first and third fingers playing the A and F# notes. Notice the difference in sound, as well as the difference in playing difficulty.

Similarly in bars 9-16 you can try keeping both fingers down on both strings, lifting one, or lifting both. Notice how it is easier and it sounds better to keep both fingers down for as long as possible.

The walking fingers title is practiced most starting in bar 21. This is a practice in both horizontal movement along the strings in bars 21-22 followed by vertical movement across the strings in bars 23-24 and another horizontal movement in bars 24-25. Practice this passage repeatedly to master both styles of movements.

Once movements are mastered, do not forget to add the dynamics and change of dynamics as this is part of the piece, so that it sounds more musical and it is not a mere exercise. Pay attention to the tension in your left hand with higher dynamics and try not to press any harder as you play louder.

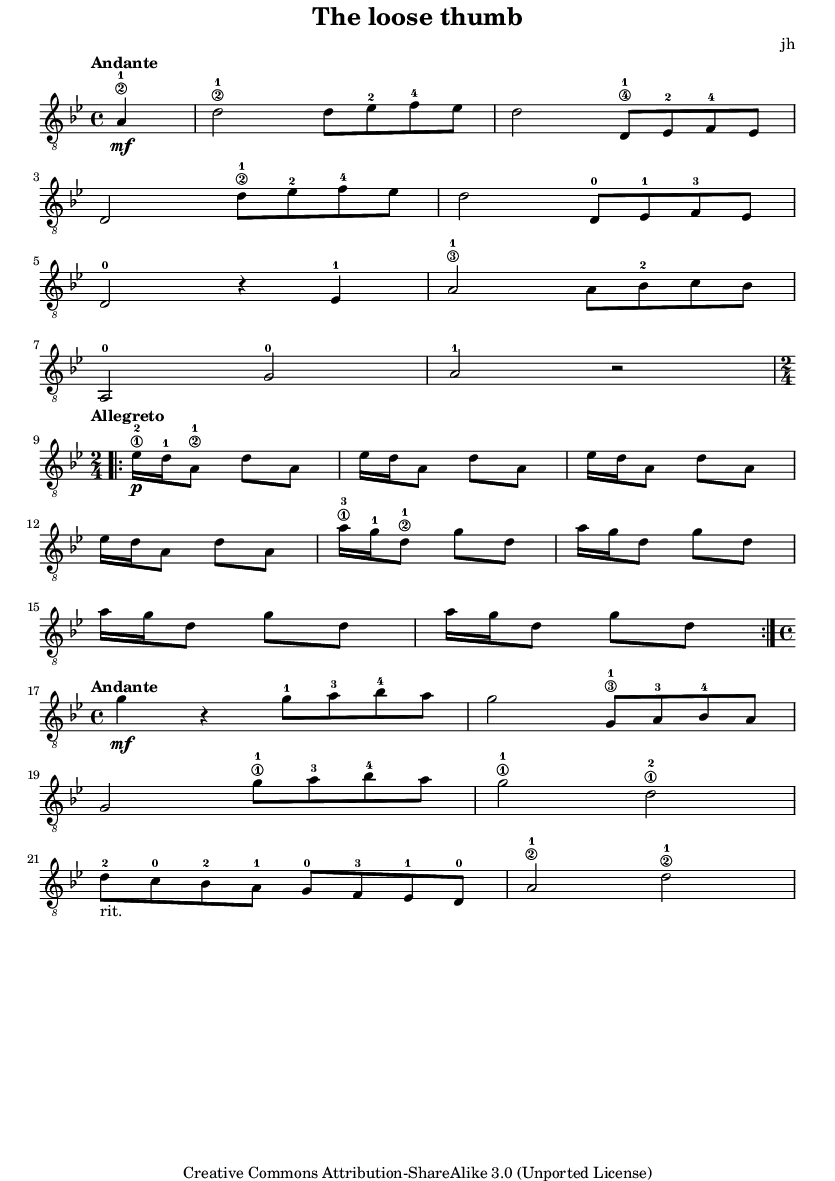

I wrote this to focus on loosening the grip of the left thumb on the instrument. I do this by incorporating lots of shifts.

Check that the thumb is not gripping, that it moves with the hand and stays parallel to the first or second finger, that the movement is smooth and originates in the elbow.

One of the advanced skills in playing the oud is being able to alternate between higher and lower octaves. The pattern in bar 1 is played in a lower octave in a closed position in bar 2 , shifts back to the higher octave in bar 3, and again to a lower octave but now in an open position in bar 4.

Bars 9-16 has the same pattern alteration between lower and higher octaves but using a longer patterns of notes.

in Bars 9-12, only lift the second finger while keeping the first finger pressed against first and second strings. Similarly, In bars 13-16 Only lift the third finger.

Bars 17-19 is another alteration between octaves but now using a shorter pattern of notes.

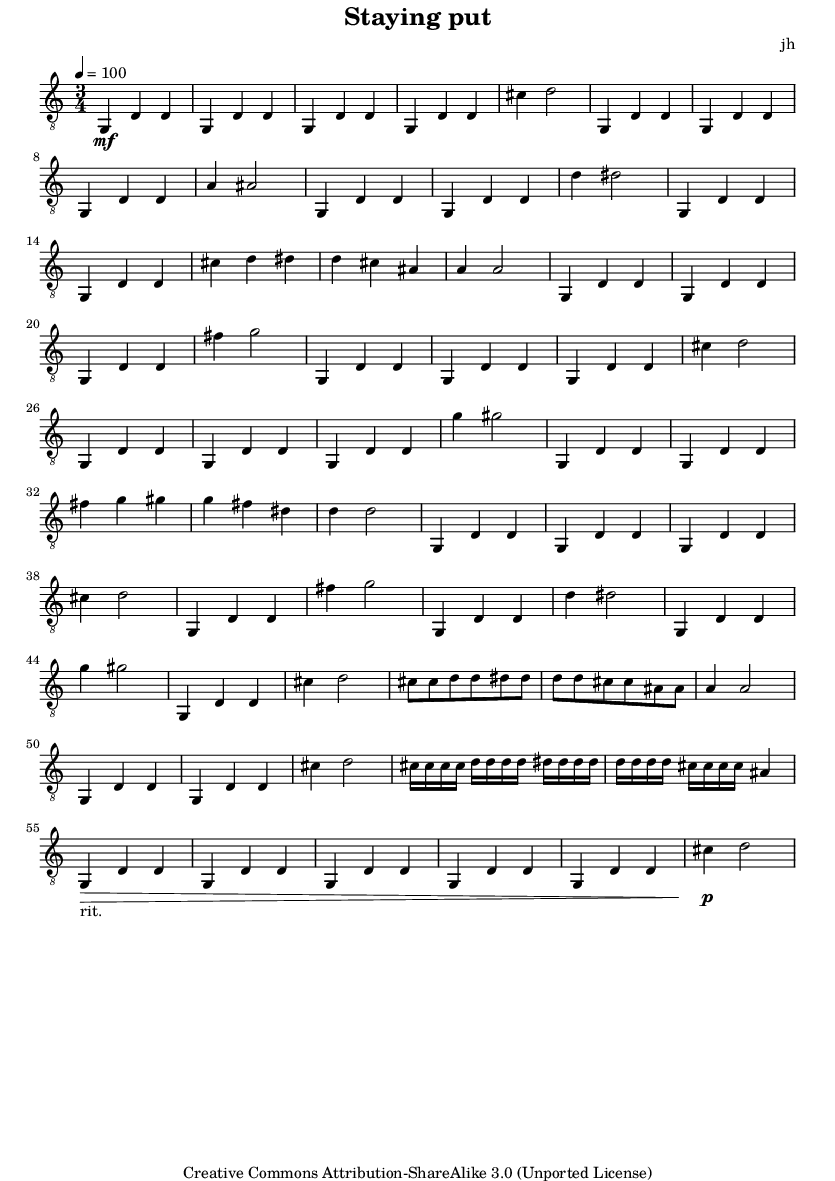

The rhythm in this piece is quite free. Long notes can be held for longer than their written value.

Learn the piece first, before adding tremolo and vibrato and substituting closed note positions for open positions. This applies in particular to the ending which starts at bar 35.

The melody in bars 25-27 can be repeated quite a few times, each with variations according to the players taste.

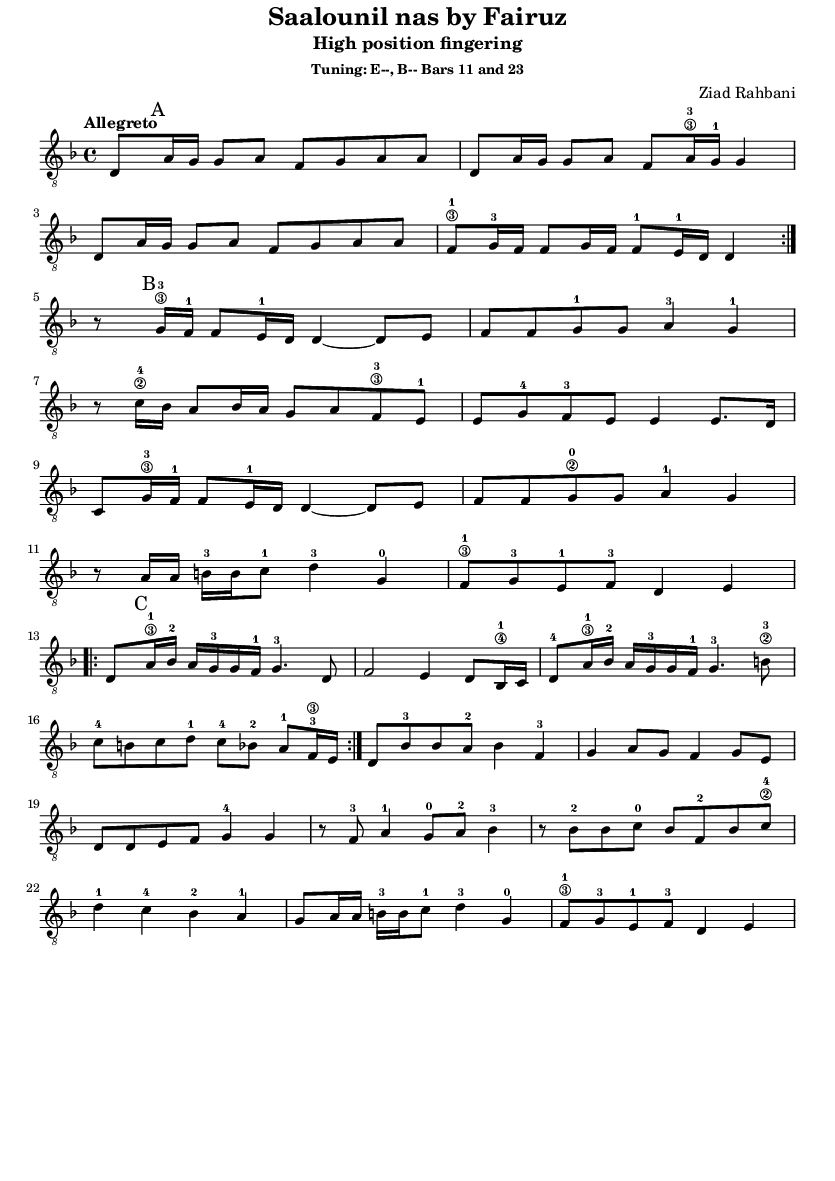

The amount of closed fingering and shifts to play this song is for practice purposes only. Only a small proportion would be needed in normal practice. Add them in slowly and gradually once you learned this song.

Note the string numbers in the circles which will help you locate the string to position your fingers for a given pattern.

You wouldn’t normally pick the fingering and shifts in bar 12, but it is a good practice to play it right and bring out the right intonation of the Arabic medium intervals. Memorize the song.

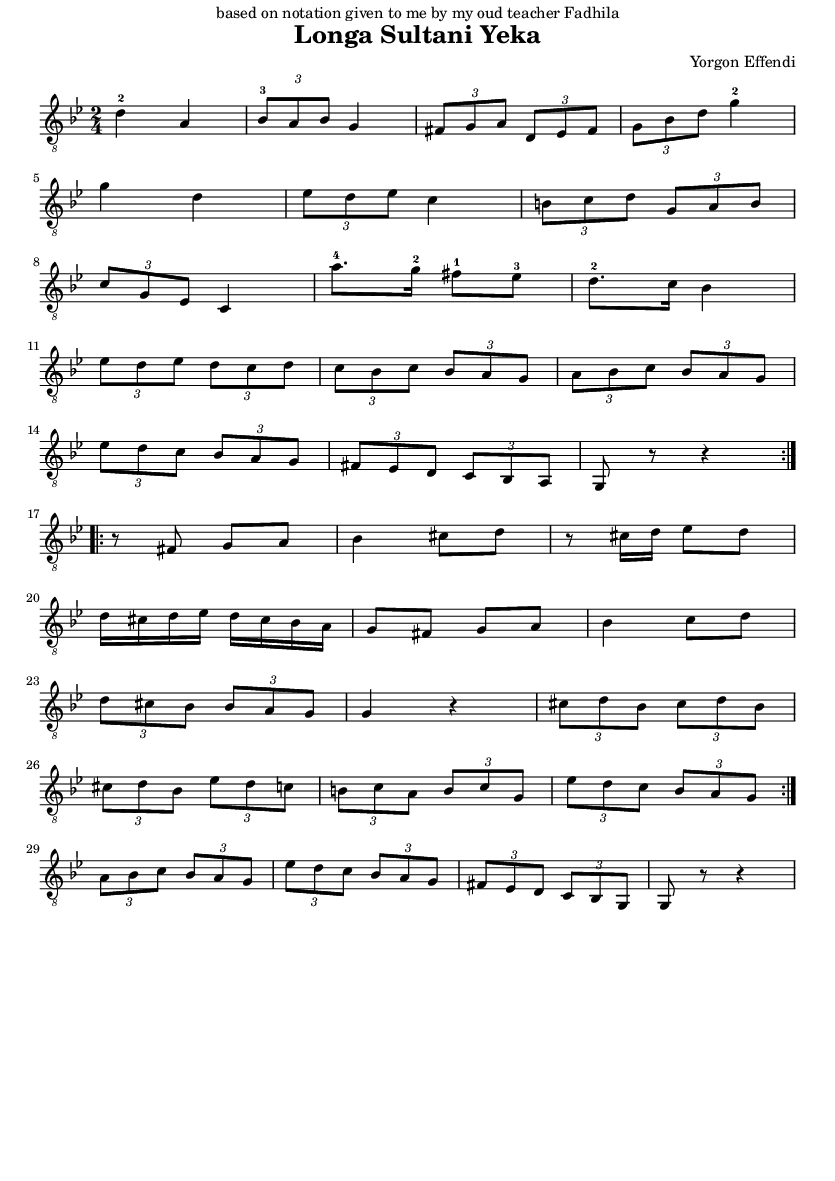

It is easy in this difficult piece to try to play it too fast and lose control. I have done this many times. Try to keep the rhythm and not rush particularly when playing the triplet notes.

The difficulty is not only in the left hand shifts, but also in the string shifts. See for example the chord notes in bar 8. Remember here what you learned in the right hand technique chapter about selecting plectrum directions and keep the plectrum close to the strings.

The repeated pattern which starts in bar 25 is easier to play if you keep the first and third finger down and only lift and depress the second finger.

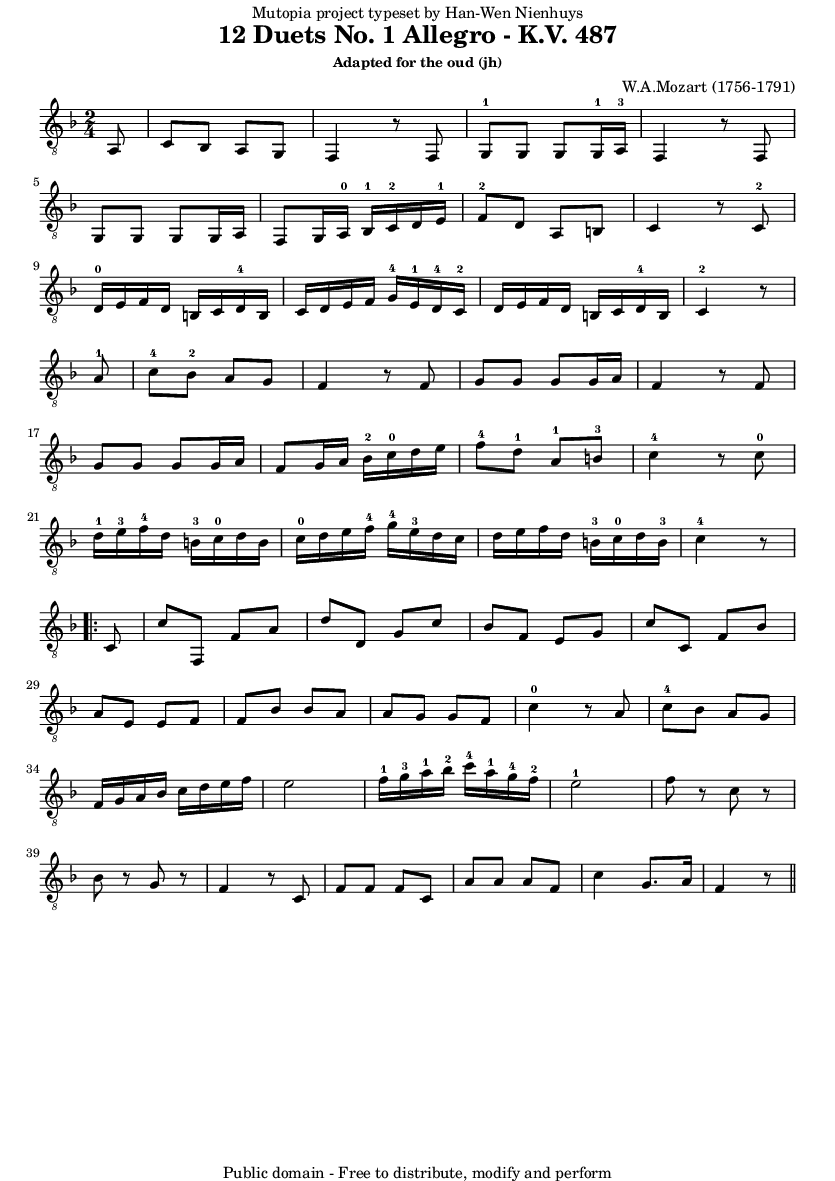

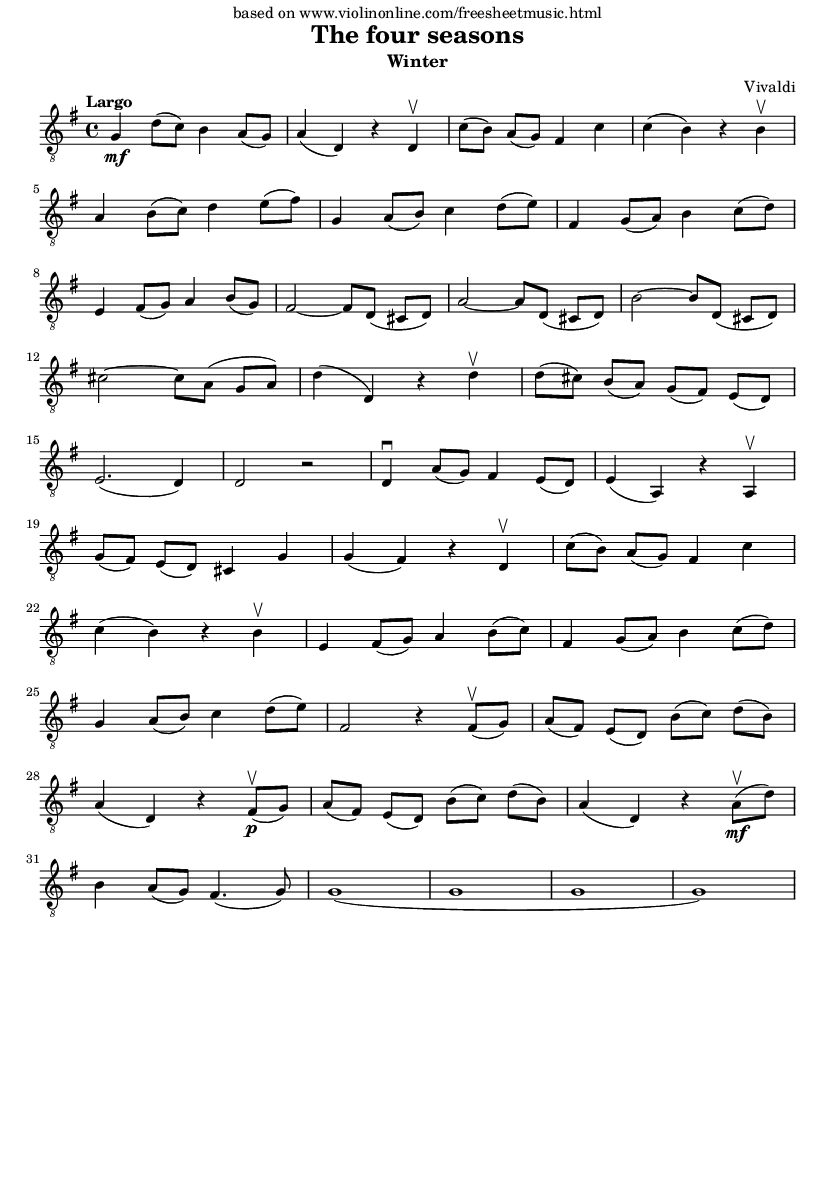

The piece is designed for violin, and it is quite difficult on the oud, because of the long sequence of short notes, some in high position.

Such a long sequence of fast notes can be practiced by slowing down the music, or by playing a shorter sequence at full speed, and adding more notes gradually.

Many players would not be able to play this well without a lot of repeated practice, but it is a good exercise for the left hand.

Each note or group of notes on the oud can be played in different positions.

This chapter is about exploring playing patterns of notes in different positions and navigating a significant area of the instrument, rather than being stuck in a narrow space as we tend to do when we begin learning.

A more advanced oud technique requires us to learn to alternate quickly between playing the same phrases in lower and higher registers, continuing phrases that started in one register in another register, or mirroring a phrase on another string. This requires us to be completely familiar with the geography of the instrument and where each note lies so that we move to it without much thinking. This takes a life time of practice of course and can be improved gradually, once we have the understanding of the various playing possibilities.

In even more advanced technique, the oud player plays multiple lines, given the impression of multiple players or multiple voices.

In advanced playing, we want to also explore the extremes of the instrument: the lowers pitched string, and the higher notes on the highest pitched string which are not played as often.

This is not just about a display of technical mastery. This alteration of higher and lower registers, and more busy playing that uses the range of the instrument produces a more satisfying and engaging music.

This doesn’t mean that every note in every position must be played in every piece. That would be too much and even dull because of the extreme variety. It just means that we need to think about how to make a given piece more interesting by adding variations to develop a given theme.

This is why, some of the exercises in this chapter (as well as in the chapter on right hand technique), are some of the more important exercises in the book. Advancing on both of these fronts alone would produce noticeable improvements in our playing.

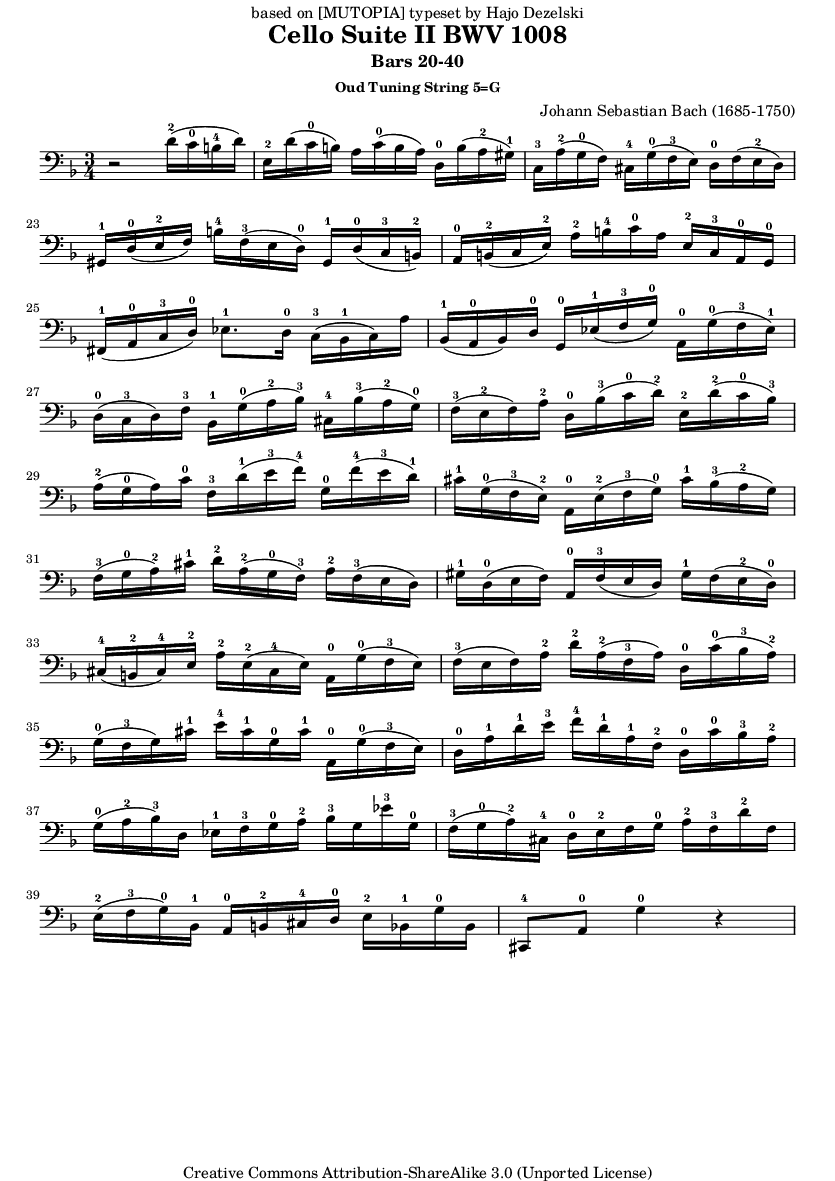

This is a somewhat difficult piece for the oud, but it is spiritual and rewarding, and I love coming back to it. Learn it one bar at a time.

I suggest retuning the fifth string to G rather than F for this piece, although you can of course try both. I found the tuning to G reduces the difficulty and it sounds a little better. It is also good to learn to re-tune the lower two strings of the oud quickly depending on the piece and scale that is being played.

Most of the movements are across the strings, so keep the left hand still and relaxed and reach with one finger to the lower notes with a minimum of movement.

This is another piece where I recommend tuning the fifth string to G rather than F.

Note that the indicated natural modes such as E natural would not match the sound of a E note on the piano, but is natural in this Arabic mode and is a little lower in pitch than E in a Western scale. Listen to the piece.

Notice how the phrase is completed rather than repeated in a different register.

Notice how alterations between notes are more difficult, when the distance between strings is greater or when the left hand position in the oud is not in a familiar playing position. Some of the more difficult alterations are placed towards the end, particularly bars 31-32.

There is not much up and down movement within the piece, but the entire piece is transposed with almost identical finger positions.

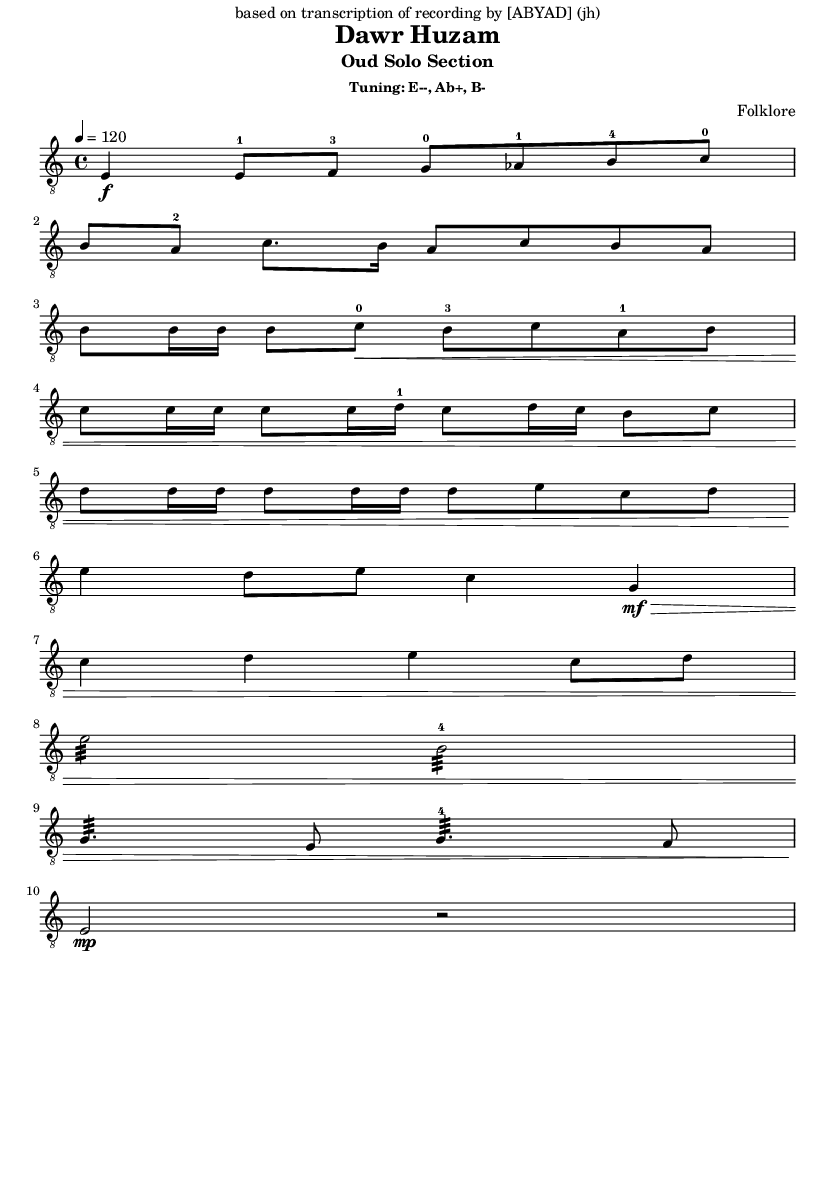

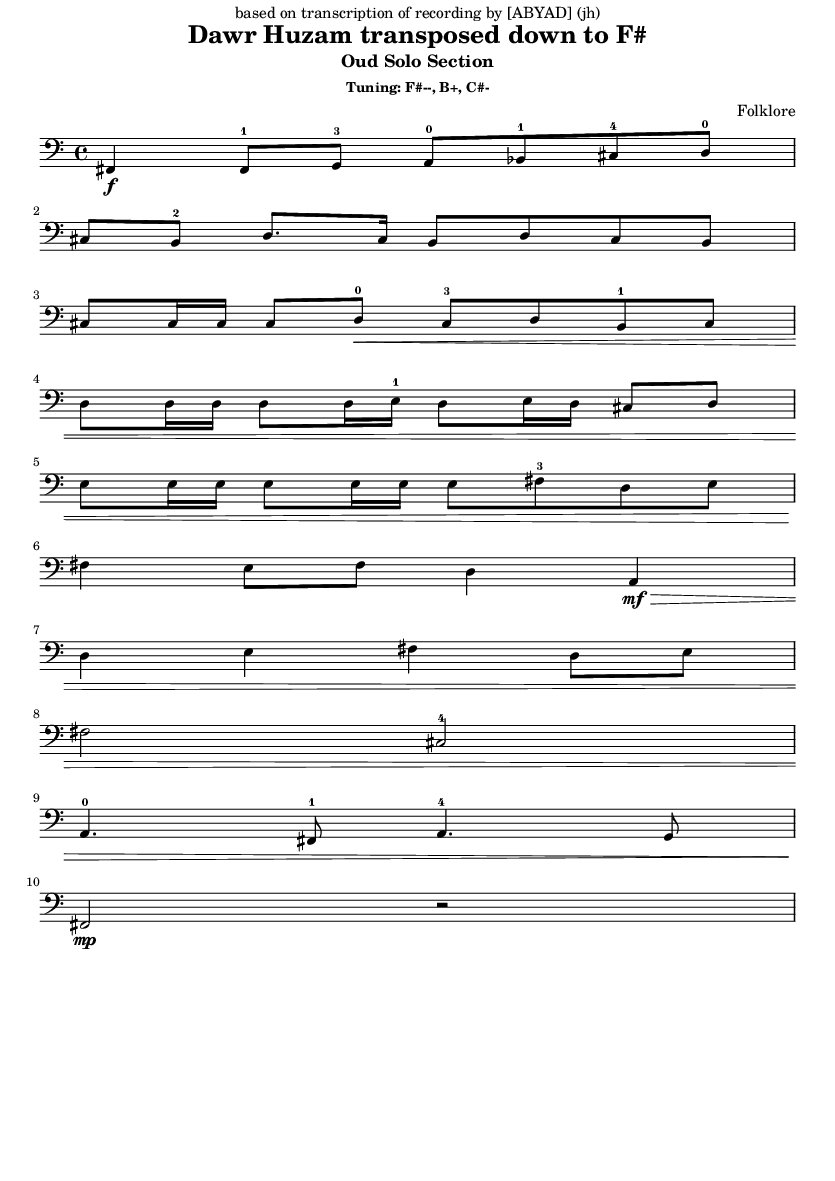

The interval between the first two notes suggests the Seka and Huzam modes. Listen to these modes if you are not already familiar with them, so you can reproduce this distinct sound.

Notice the different sound and atmosphere between the original and transposition. Also notice the different effort involved. We need to dig in more into the lower and thicker strings in order to get a satisfying sound.

This pieces relies on two themes played in different registers. The theme in the upper register is developed and becomes more elaborate, while the lower register theme simply comments.

Pay particular attention to the dynamics in this piece, as it distinguishes both characters. This use of dynamics is not a very common technique in Arabic music, but a question and answer approach is. Playing softer also makes it easier to play the more elaborate run of notes in time.

Pay also attention to the transitions between the registers. It is meant to be a continuous conversation where no part interrupts the other, and where there is no long and awkward silences.

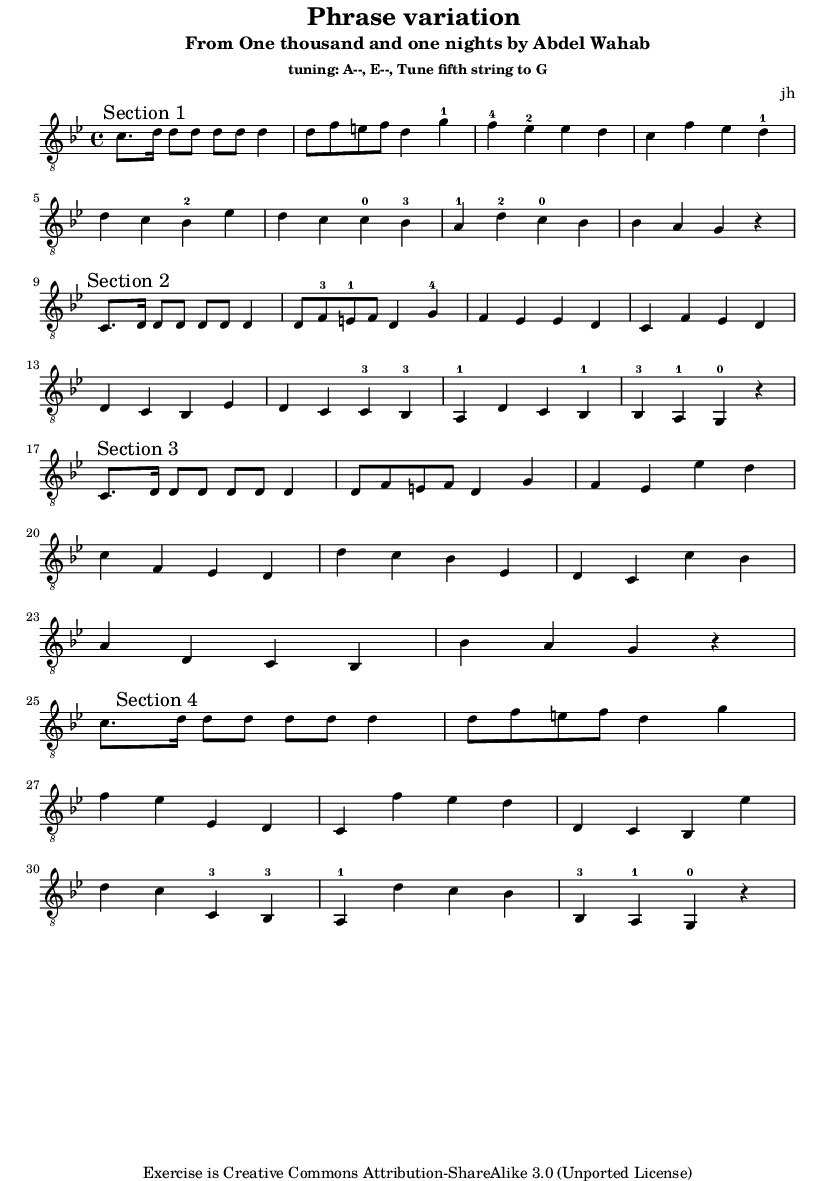

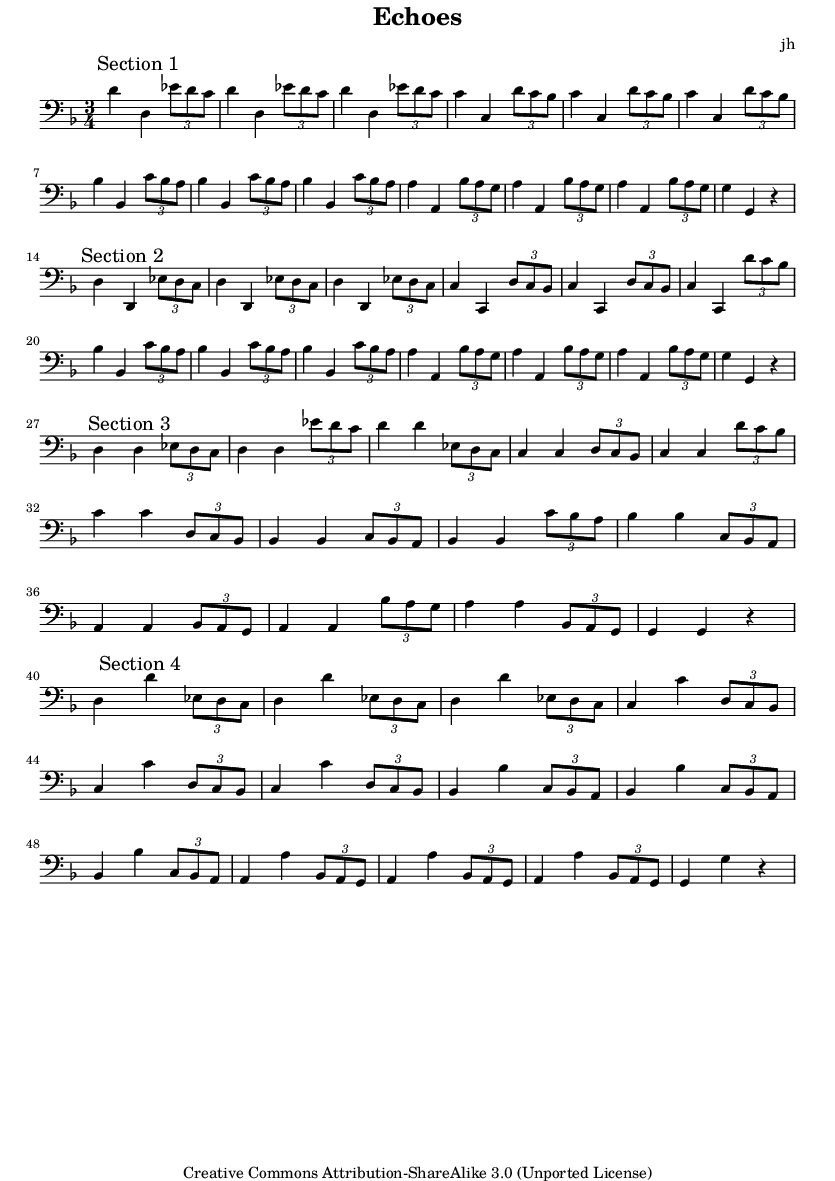

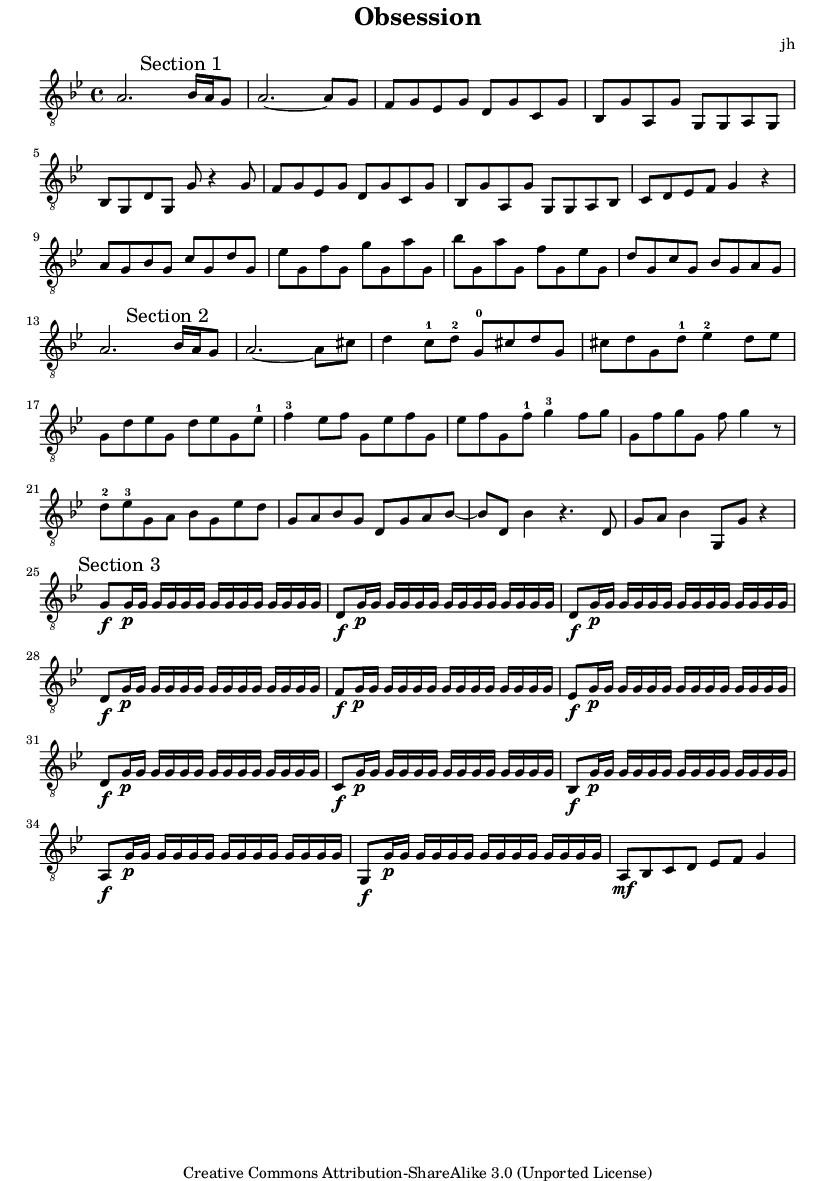

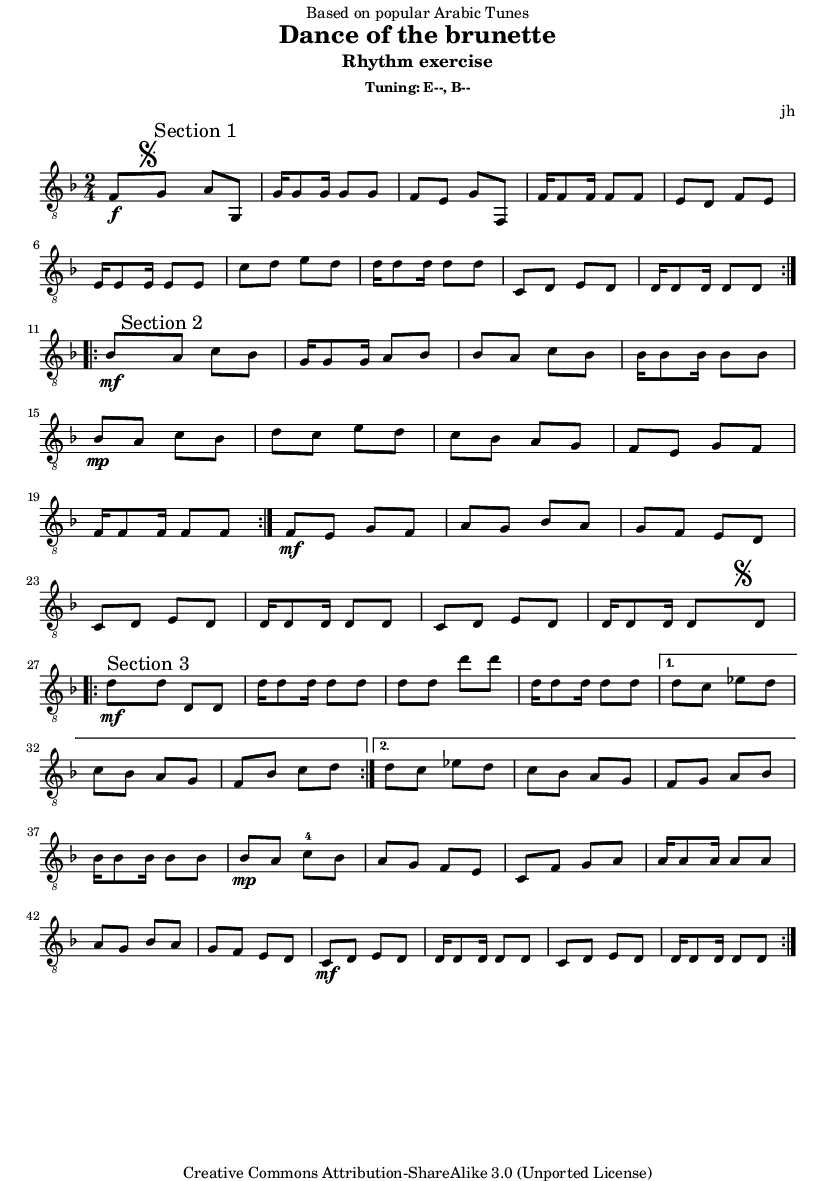

In section 1, some notes are substituted with notes in a lower register. This is a basic technique that must be mastered on the oud. It is easier to position the hand right after the previous note in the higher register is played, so that we have more time to hit the echoing note cleanly.

In section 2, We start the whole melody in a lower register until we run out of lower notes that can be substituted and we transition the whole melody up again. This transition which happens in bar 19 is the most difficult part of this section so it has to be practiced more often, until it is performed cleanly.

In section 3, we transpose phrases rather than individual notes, which is more difficult and harder to master since there are more combinations of phrases than individual notes.

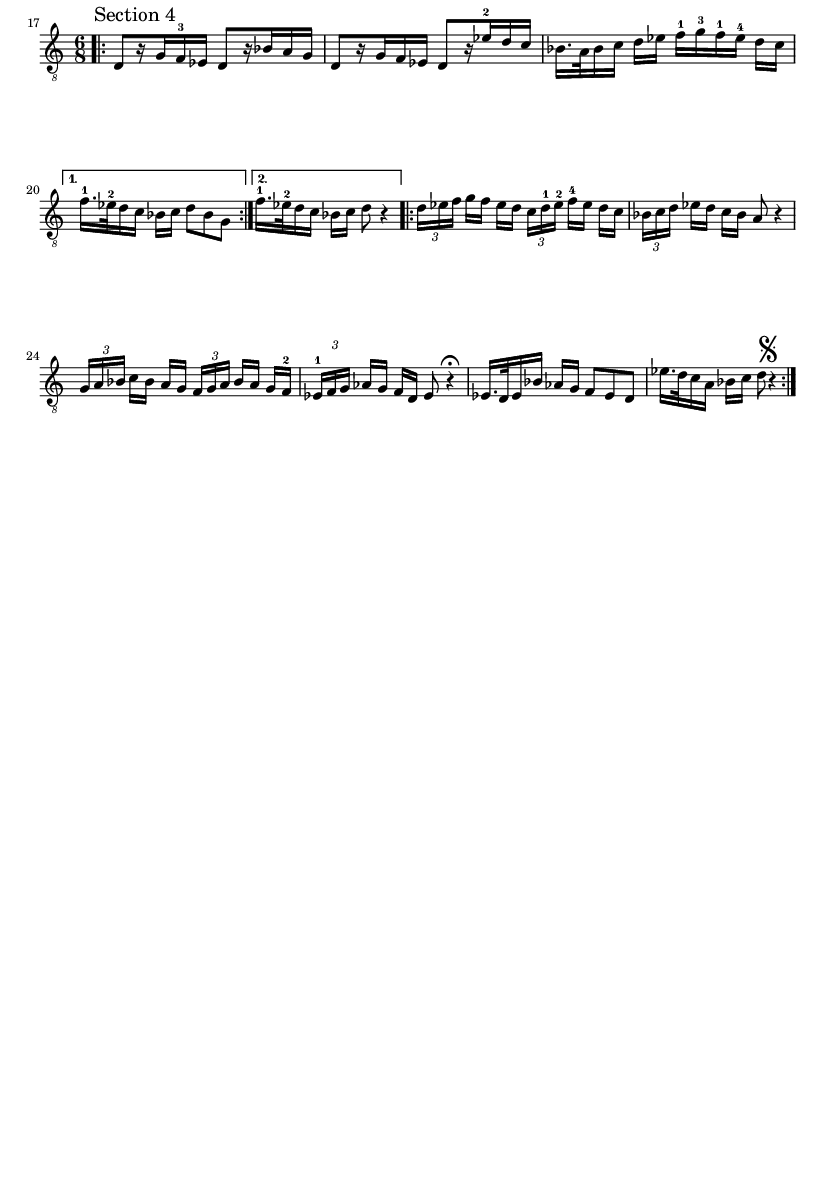

In section 4, we return to substituting individual notes as in section 1 and 2, but now the substituted notes are in the higher registers which is less common, but have a more energetic effect.

The piece starts with a scale but it is actually difficult to play because of the alterations after each beat until we practice enough to learn how to echo each sub-phrase in a different register.

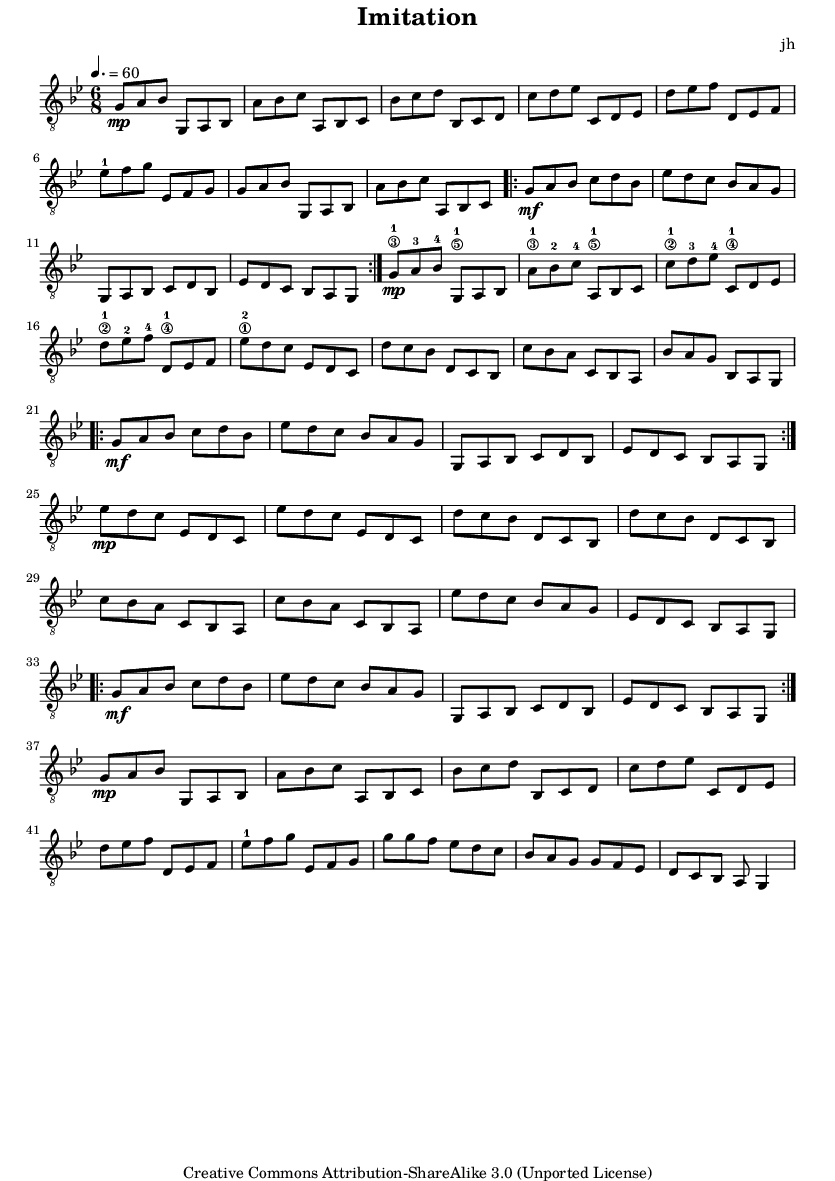

At fast speed, it is easier to count 6/8 rhythm as two beats per bar. Constantly check the first note of each triplet matches the fall of the beat.

Bars 13-15 are particularly difficult, but it might help to remember that in closed position the fingers have the same configuration in both registers, so we just have to get the first note right and this configuration right without having to think about individual notes.

The melody is in bars 8-12 and is repeated. You will notice that it is easier to play a longer melody in both registers than to constantly alternate after each short phrase.

This exercise also simulates what we should do in practice, which is to take a more difficult segment of a given piece of music and focus our practice on it.

Section 2 is more challenging, but try it by starting in a higher position with your first finger on the neck of the oud, and experiment with shifting up and down where necessary.

Notice in section 3 how we get a multiplier effect of learning when we learn by patterns, as we learn a pattern of notes on one string, then we already know how to play all similar patterns on other strings.

In section 4, we deviate a little from the tune to have a bit of fun, then return to it. This type of play within the existing repertoire is how we learn to improvise.

Section 1 illustrates the use of ostinato on a single fixed note which could be in the lower or higher registers.

In section 2, the alterations with the ostinato note is after each short phrase, rather than every note. Notice the different musical effect.

In section 3 we combine the ostinato note with a tremolo while we move away from and towards the ostinato note. Pay attention to the dynamics that emphasize the moving note. Emphasize the first note of the tremolo and keep the rhythm - Play the piece slower if necessary. The musical effect is dramatic and emotional.

In this piece, there are no quick alterations between lower and upper octaves. However, the same melodic phrases are echoed in lower and higher register as the music develops into higher registers then falls back to end the piece.

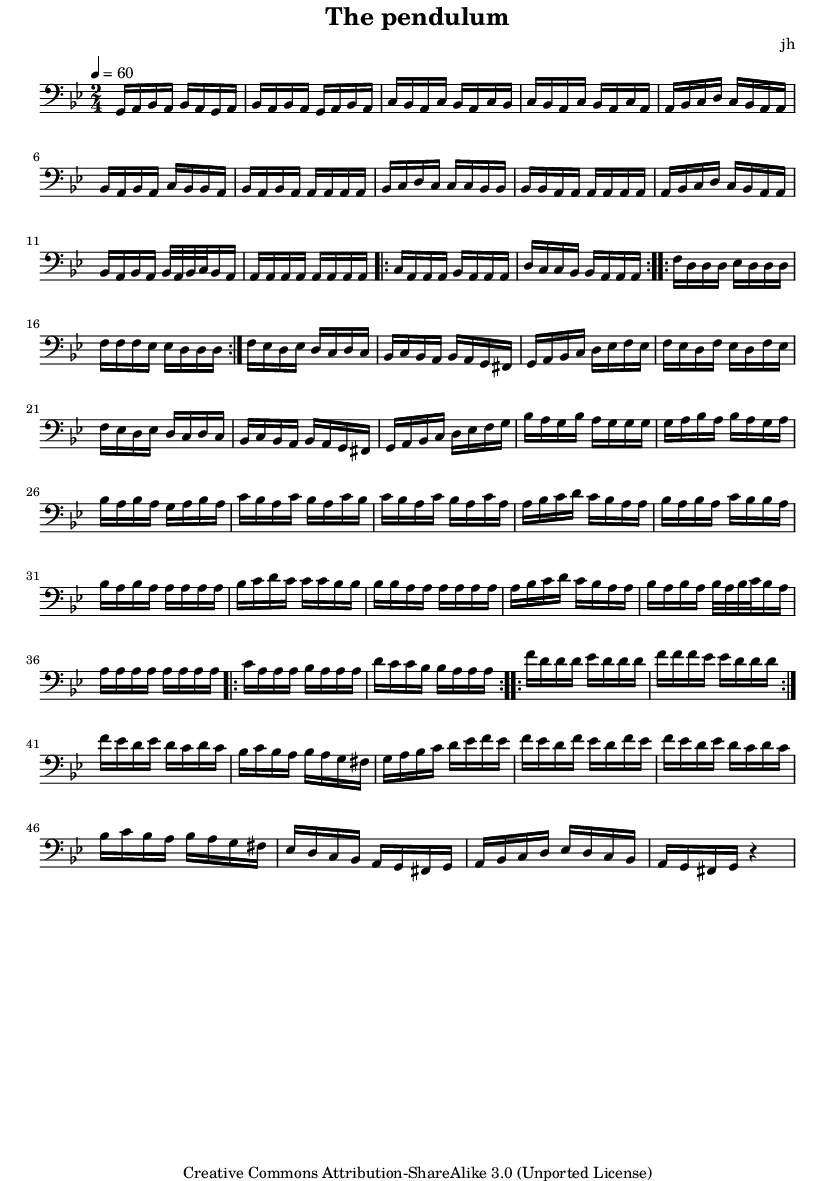

There are no large jumps between note pitches or alterations of rhythm, but the closeness, repetition and continuous flow of notes presents another difficulty which requires practice and concentration.

The melody sections in bars 13-16 and 37-40 can be repeated few times before you are ready to move on.

The ending at bar 41 onwards is a little more difficult because of the need to read the higher notes in the bass clef and the need to use the fourth finger so practice this part more until you are comfortable with it.

In this piece, the ostinato is a phrase rather than a single note. Try to make it sound even. Keep the volume and speed steady.

Practice bars 53-54 slowly at first and gradually increase the speed to the speed of the piece.

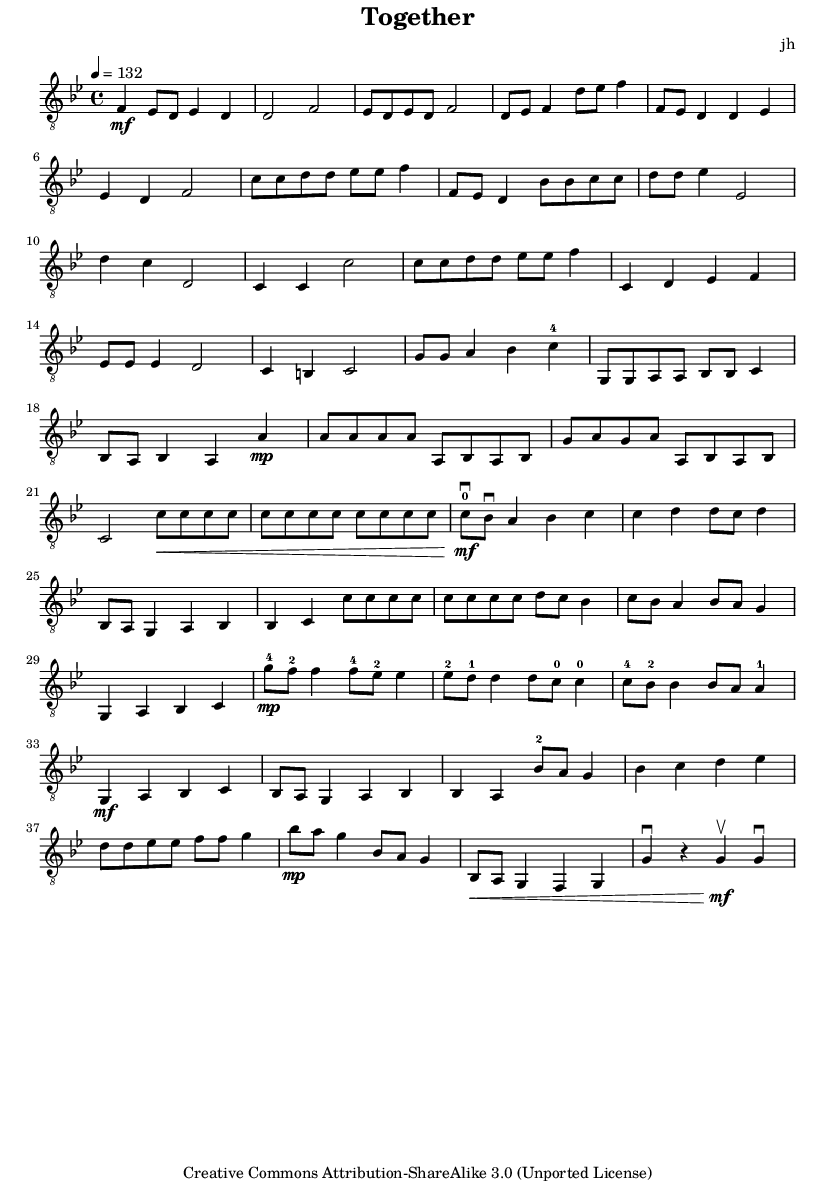

The melody is the same as that in the "Apart" piece, but the two voices do not develop as independently and are not as distinguishable.

The phrases in the higher registers such as in bars 30 and 38 are more difficult and require more practice particularly when they are followed with a transition to a lower register as in bar 38.

The reason for picking this piece (besides being a beautiful melody, and that we are exploring different types of music for the oud) is that selecting a different piece that emphasizes harmony forces us to break the linear melodic movements that characterize Arabic music and to explore different movements on the instrument.

It is better to avoid using the fourth finger so that higher pitched Western notes are reached cleanly. We can do that by playing in first position for most of the piece, and moving occasionally to half position.

I included the violin markings as is, in order to indicate the feeling of the piece, but explore deviating from them slightly if it works better for you on the oud.

The subject of Rhythm is quite vast and is a lifetime learning project, so we will not cover it all in one chapter of exercises, even when the application is limited to one instrument. Good rhythm is a basic ingredient to our enjoyment of music, and is related to another basic human art which is dancing. It is something that we can improve on gradually and even away from the instrument.

Practicing with the metronome is quite useful to understand rhythm and to pinpoint mistakes, but practicing with a musical group is a lot better, as the rhythm of a group is typically flowing and we need to be adaptable and not so rigid as when we practice with a metronome.

There are many ways of keeping in time, such as counting 1, 2 1 and 2 etc or making up word syllables such as dum taka-taka taka-tek for more complicated rhythms. We can tap our feet or use a metronome or listen to a drum beat, but the constant aim is to feel the beat. It is a feeling and not merely a mathematical recognition. When the beat is really slow, we can help keep the time by subdividing it or doing an action such as tapping the foot during silence. When the beat is very fast, we can internally keep track of a slower beat that groups many of the fast notes.

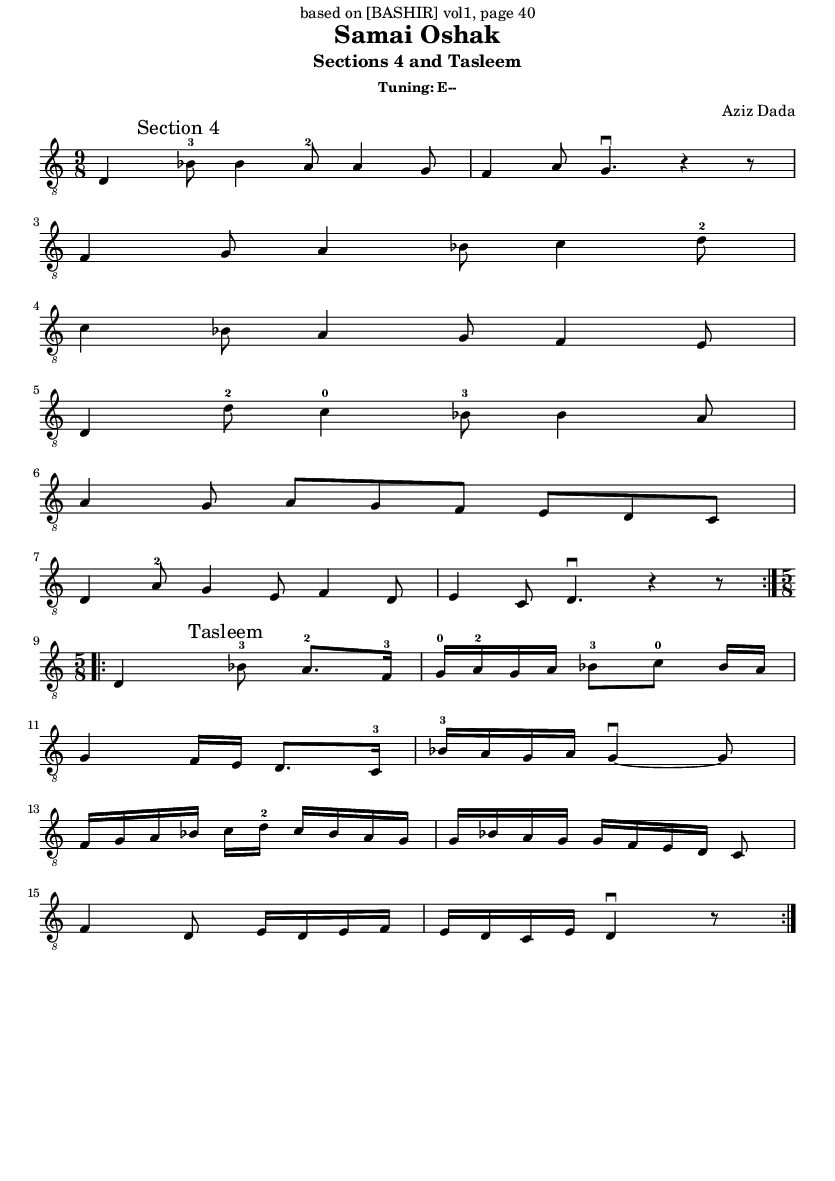

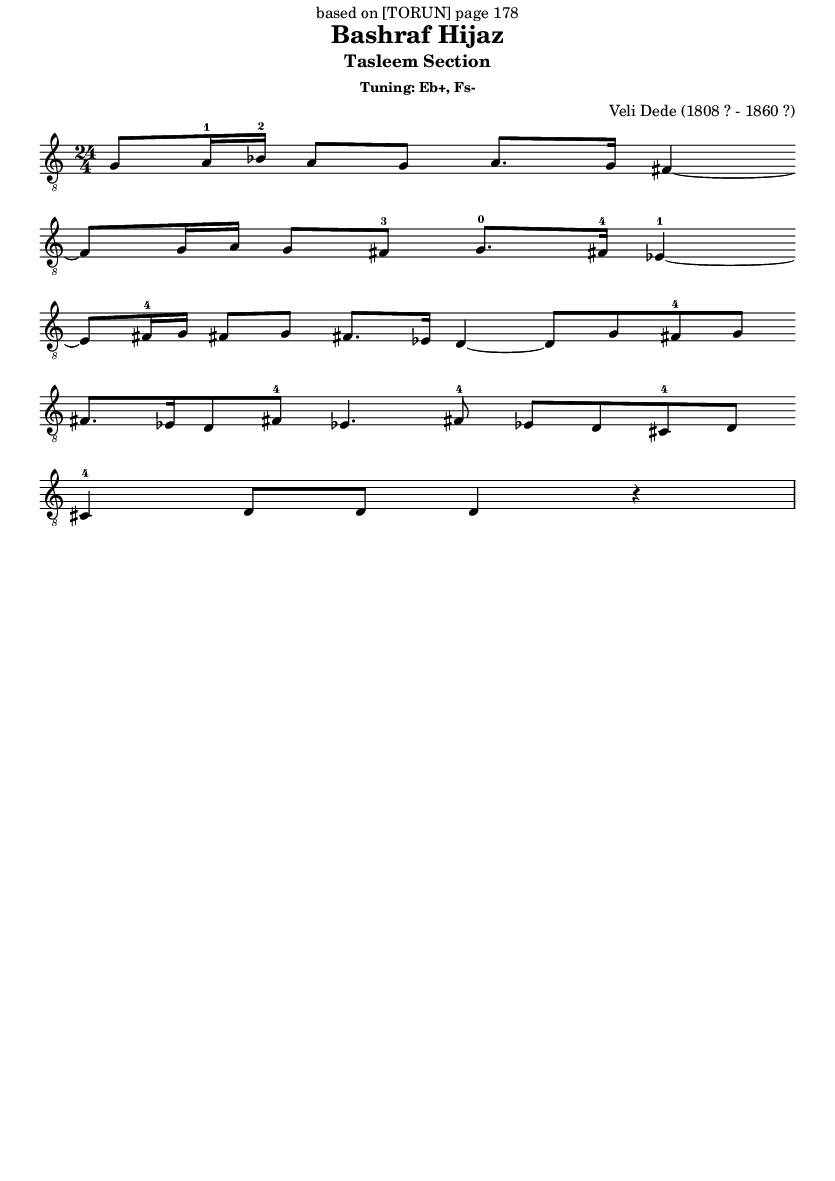

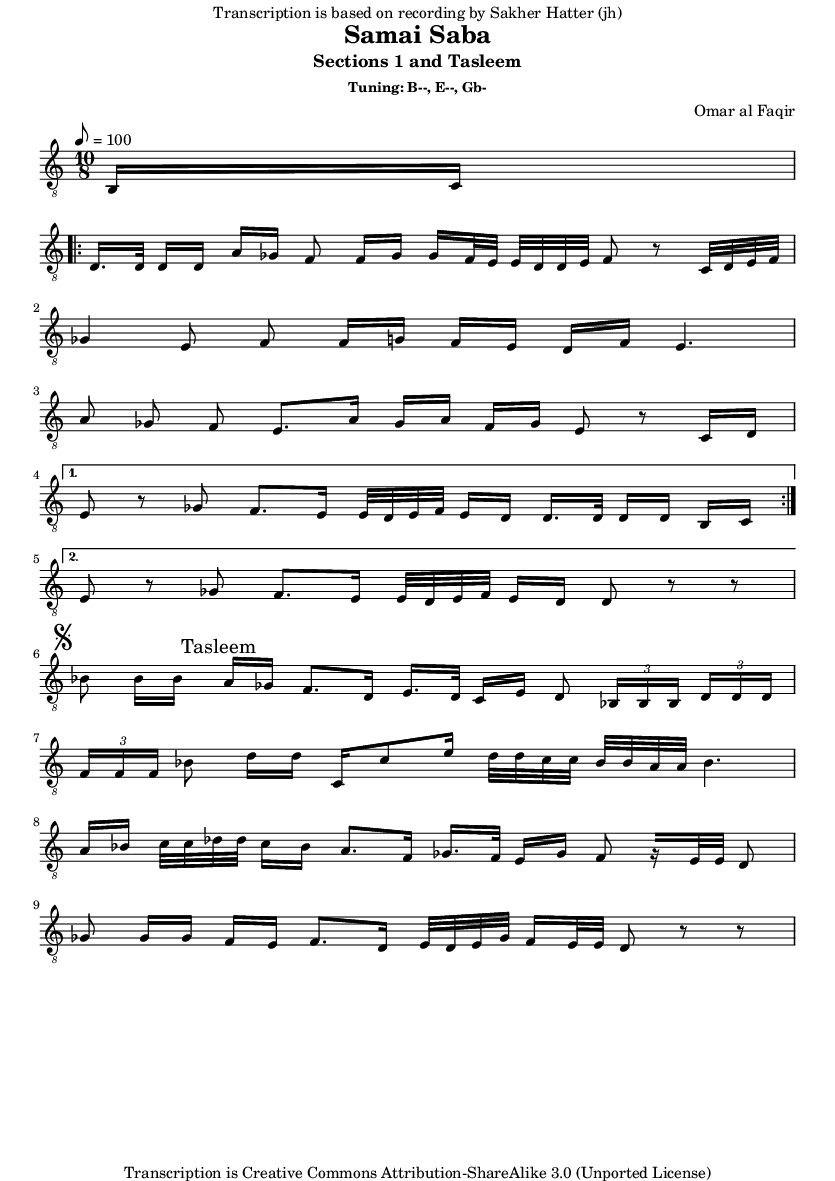

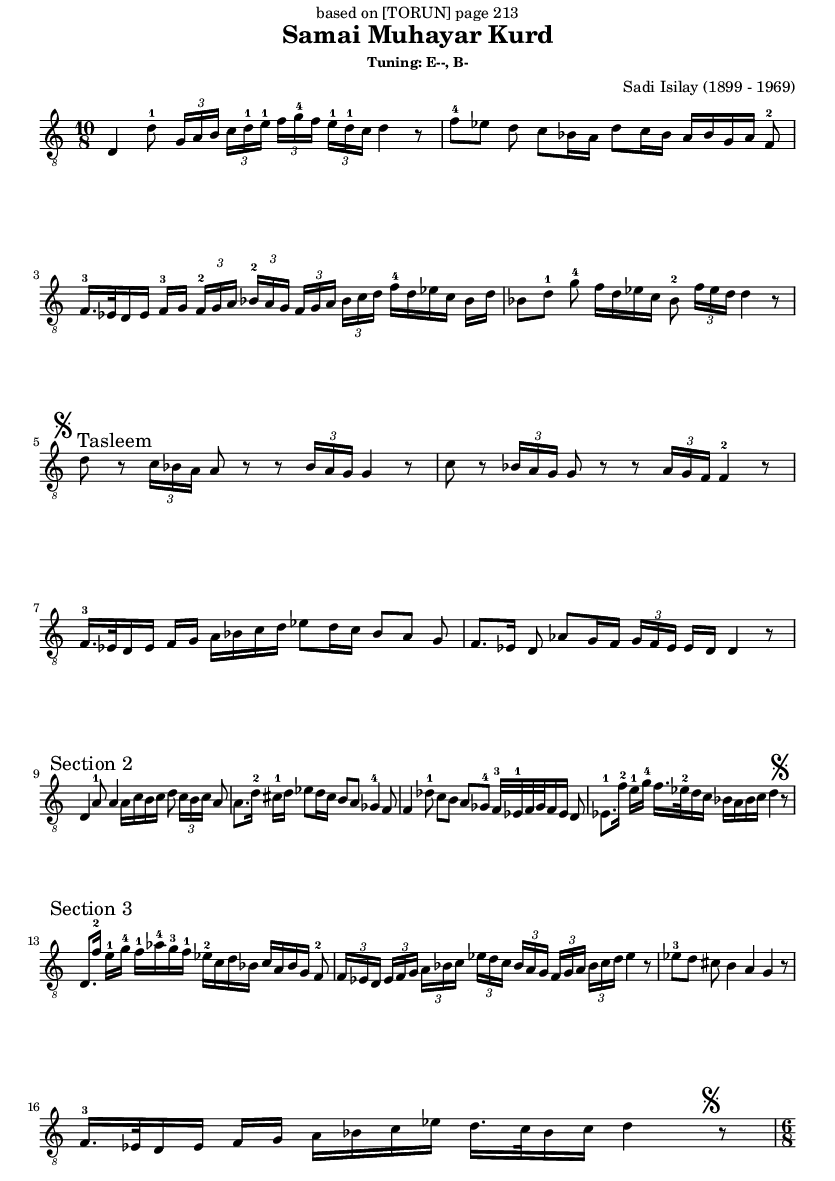

Arabic music contains many complicated rhythms so the subject is quite vast. Some of the more common rhythms that are encountered by oud players are the 10/8 rhythm of the Samai form, and the 6/8 rhythm which occurs at the end of this form. 3/4 and 6/4 rhythms are also often used as well as the 4/4 rhythm of the Bashraf form. Syncopated rhythms are also quite common. Some of these will be encountered in this chapter and in the rest of the book.

On the oud, a good rhythm technique goes together with a good right hand technique as it is the right hand that controls the timing of the music, and the articulation and emphasis of notes.

As beginner players on the oud, we have a problem that the notes die too quickly in basic playing, so there is a temptation to fill the silence by rushing or skipping silent notes or losing the timing as we attempt tremolo. This is made worse by the fact that we often practice the oud alone and not as part of the group, so we may not be aware of the cause of why the music is not sounding good despite all our added efforts.

No elaboration will make the music sound good if the rhythm and the beat are lost, so if that happens we need to always return to the basic rhythm of the music. There are techniques that we can use to fill in the silence such as doubling the notes or embellishing them or playing tremolo or alternating between lower and higher octaves as explained in the rest of this book, but we can only build this on a solid basis which is a correct rhythm, and we cannot be lost in the embellishments as to lose awareness of the beat of the music.

recording using - iphone 7 - 17 July 2022

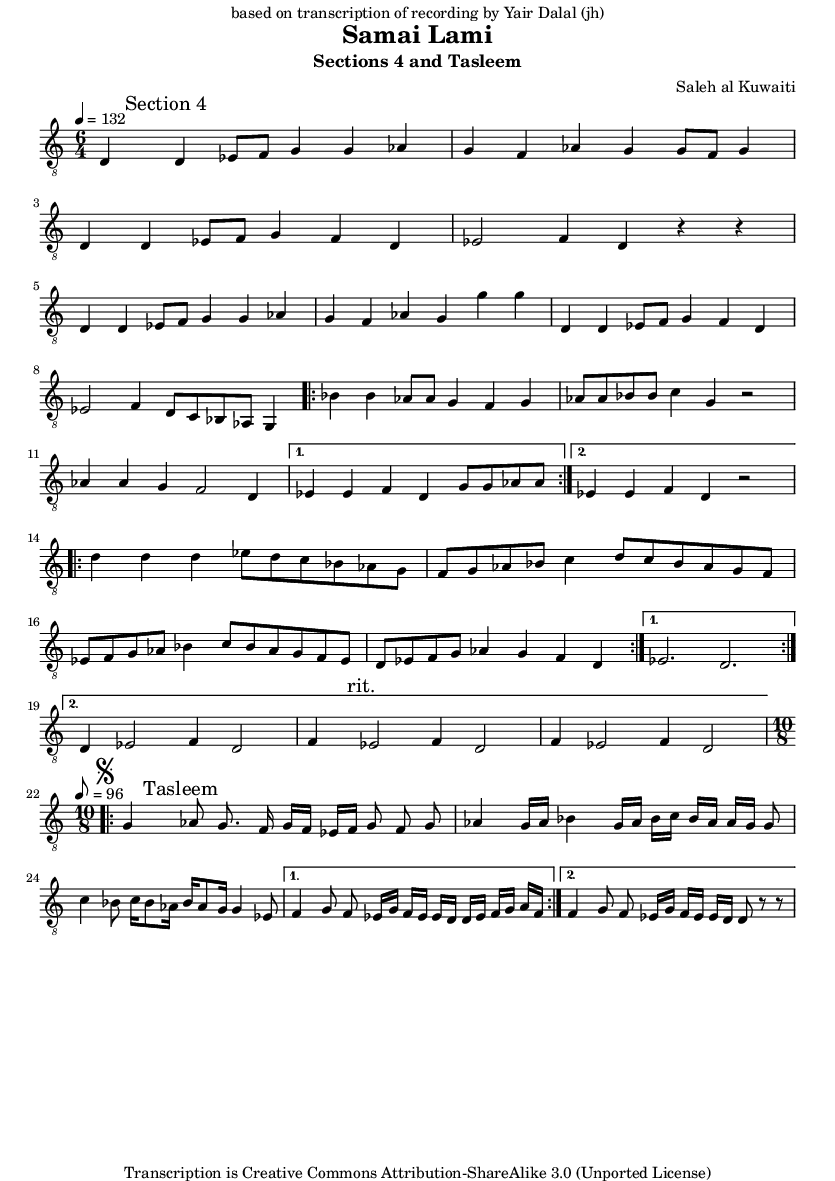

The Samai rhythm is very common in classical Arabic music. It is a 10 beat measure of DUM-S-S-TEK-S-DUM-DUM-TEK-S-S Where DUM indicates a strong emphasis (The Drum player will hit the middle of the drum), and TEK indicates a weak emphasis (The Drum player hits the edge of the DRUM) While the S indicates silence or no emphasis which is played on the drum with softer embellishments. If we take the DUM beats only, the emphasis is on beats 1, 6 and 7. If we include the TEK beats, the emphasis is on beats 1,4, 6,7 and 8.

In this piece, I have indicated the position of the DUM with a D, and the TEK note with a letter T to show how it aligns with the music.

It is quite difficult and requires a lot of practice to be able to count to 10 while playing the oud, and to be able to be aware of the position of the strong and weak beats. Practicing with a rhythm player who is responsible for the counting helps a lot. The subsequent DUM beats tells us that we are on beats 6 and 7. The strong beat at the beginning of the measure also can help us align.

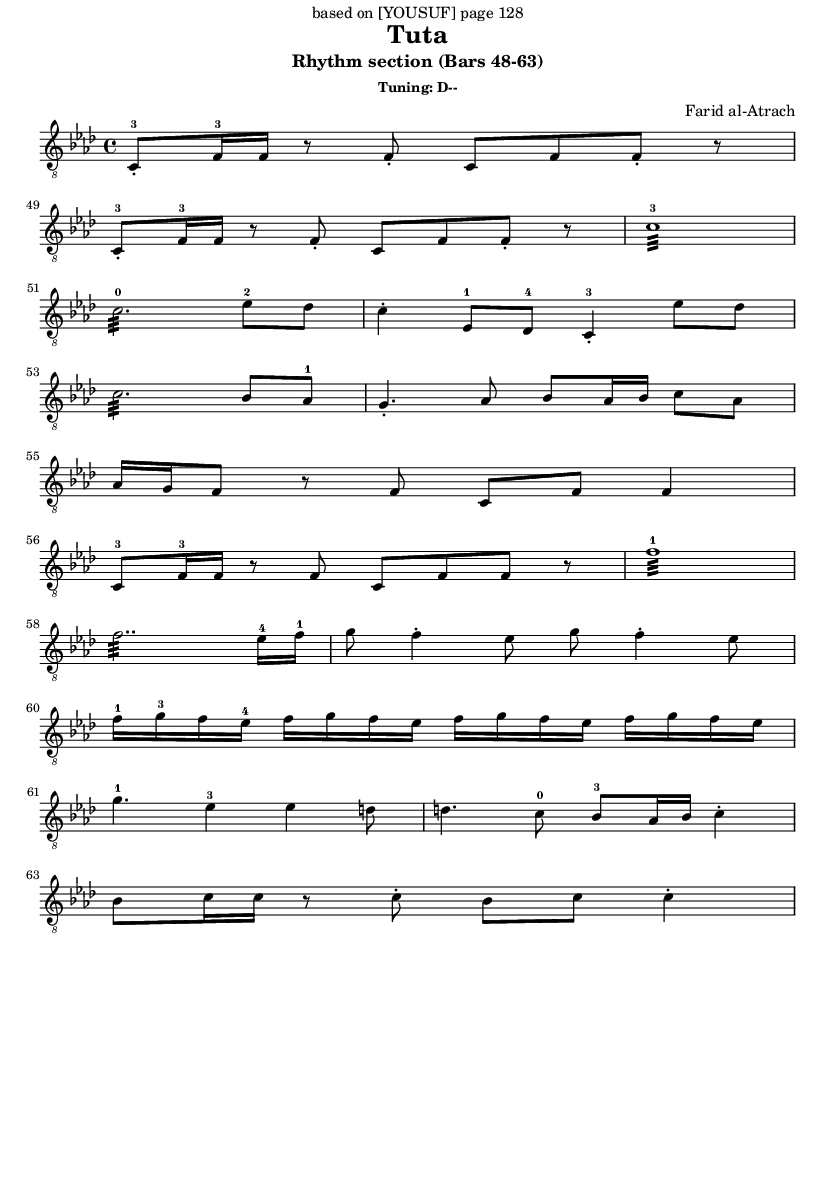

The rhythm is given in bars 48-49 and 63 - Practice these bars separately.

Add the tremolo notes after you memorize the piece and the rhythm is ingrained.

The fast notes in high position in bar 60 are awkward to play. It is however made easier by the fact that the fingers are already in this position in bars 58-59. Try moving the entire hand so that the thumb aligns with the first finger and keep the fingers round so that finger 4 does not touch finger 3 or the first string. In this position it should be possible to play these notes by only lifting finger 3 up and down.

Note the transition to the Bayati Mode on C in bar 61. The D natural is the natural D of the Bayati on C scale and is lower in tuning than D on the piano. The C-D interval in the Bayati scale is roughly a 3/4 tone and has a distinct Arabic sound. Try to find and listen to a recording of this piece, or use the web site link towards the end of this book.

The piece is relatively complicated given the changes in rhythm. Notice however that the beat is steady for most of the piece and is only faster at the end at bar 35+. This beat should be held steady by using a metronome or softly tapping the foot, and fitting the various rhythms by subdividing this beat.

If you are like me, there is always a temptation to rush through the triplets. Hold the beat and align the start of each triplet with the beat.

In bar 24, the notes are very fast so keep your right hand close to the string and use up down movements of the plectrum to fit them in. It is better to miss a note or two than to miss the beat.

In bar 29 the rhythm changes and the music is faster as the speed in the previous bar is effectively doubled by holding the speed of the beat but doubling the notes within it. The emphasis of notes is also different.

In bar 35, the earlier theme using the triplets returns but is slightly faster and more energetic before the piece ends. It is not important to get this speed difference exactly right as long as the change of speed is noticeable.

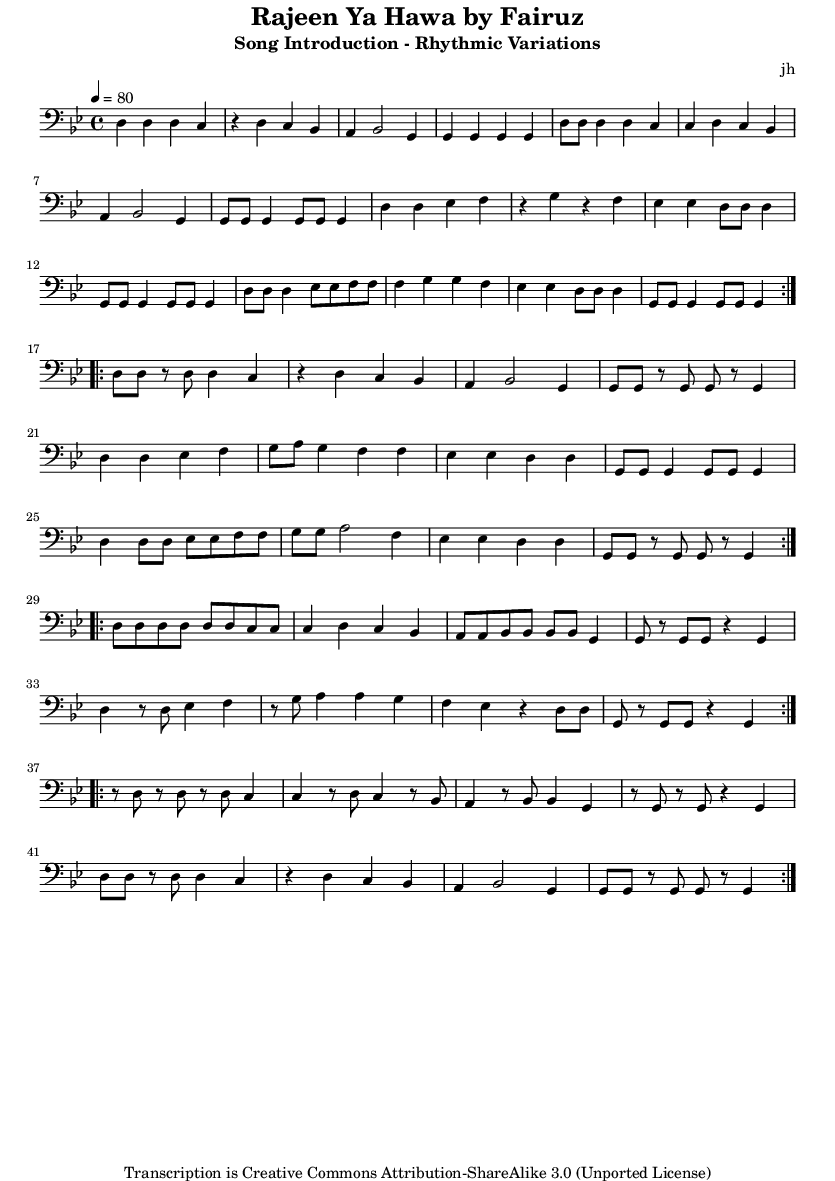

In this piece we explore some of the possible rhythm variations in this Lebanese song.

One of the simplest and effective ways in which we can vary rhythms on the oud is by doubling the notes. Notice for example how the notes in bar 13 simply double some of those that were played previously.

Another way is to syncopate the rhythm as in bar 17. If you have trouble with this, tap your feet to the music and don’t play on the fall of the foot as in other notes but when the foot is in the highest position in the air. (Alternatively stop playing, tap your hand and sing the music - Align the silence with the tap of your hand on the syncopated note).

Another mistake that we often make as beginners is to skip the silence. It is very tempting to skip the silence in bar 40 as it breaks the pattern in previous bars.

Bars 41-44 deviate quite a bit from the song as an exercise in syncopated rhythm.

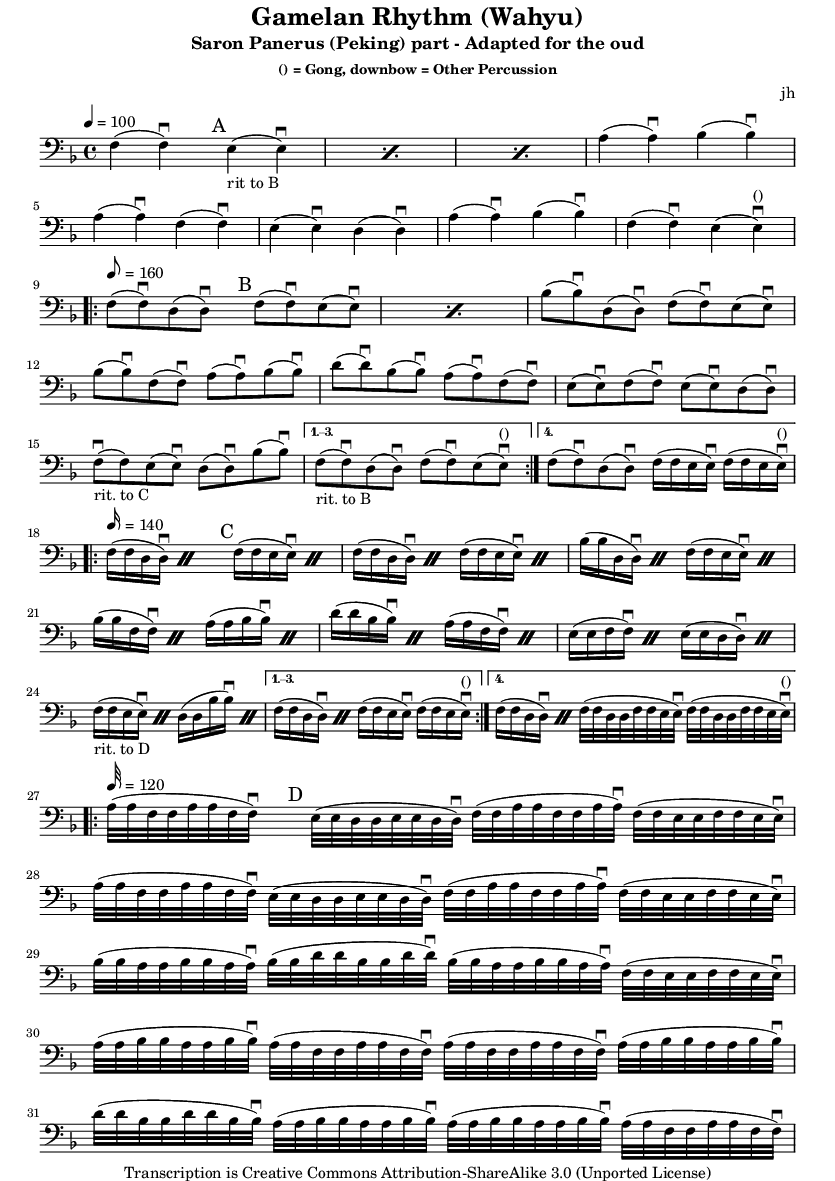

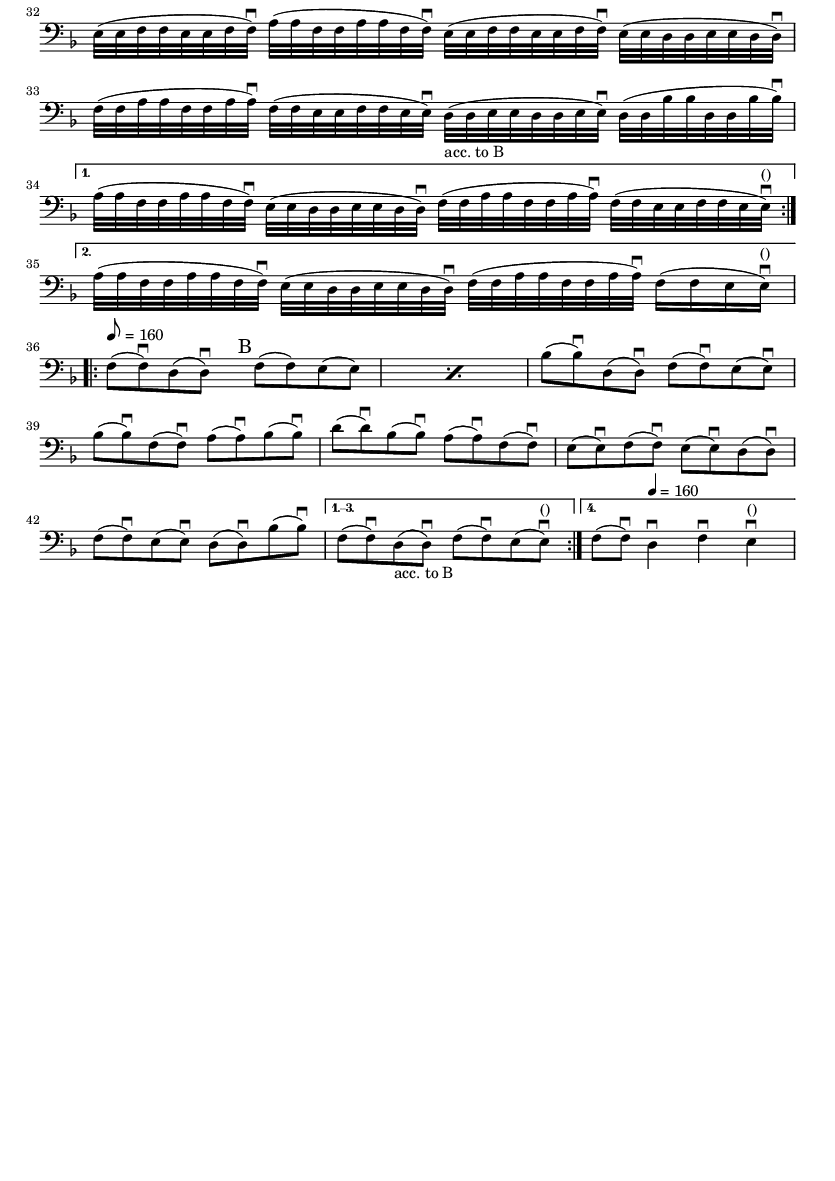

The aim of this piece is not to accurately transcribe gamelan music for the oud, but to illustrate an alternative technique of altering the actual beat during playing rather than subdividing it differently when the music is composed. This adjustment to different beats during performance is quite tricky and requires active listening and reacting to the different speeds of the music.

The transition is hard to practice alone so you need someone else to vary the speed for you, alternatively do it by tapping your feet and slowing down the rhythm (This is more tricky to do as you have to worry about doing this and also playing the busy notes).

The beat is shown by a down-bow sign, and is played by melody instruments, while the written music is for the embellishing instrument. This slowing down is controlled by the beat of the drummer.

During the first 8 bars the music slows down gradually and the sounding of the gong at the end of bar 8 signals for the embellishing instruments to double the notes without rushing as the music transitions to section B.

The music in section B is cycled few times until the Drummer starts to slow down the beat gradually and significantly so that the embellishing instrument has now enough time to play 4 notes per beat and the music transitions to section C.

Cycle C is repeated few times and the drummer again initiates another deceleration of the beat until it is extremely slow (Roughly 4 seconds between two beats). This allows the embellishing instrument to play 8 notes between the beats in section D.

Cycle D is now repeated few times and then the Drummer alters the speed again but now accelerating until the embellishing instruments cannot fit the notes in, and have to return to less embellishment of the notes. The music continues to accelerate before it slows down again for the finish.

We can almost adapt to any complicated but constant rhythm once we memorize it, but it is the changes in rhythm that are more tricky. This exercise contains many more sudden changes than the average piece.

Ensure you count the silence in bar 8.

Check that the triplet rhythm in bar 13 is different than the rhythm of the previous notes in the same bar. The same mix of these two different rhythms is in bar 14.

Tap your feet in bar 22. Only the last note in the bar is on the beat and should align with the fall of the foot.

Silence on the beat that is followed by 16th notes as in bar 23 is tricky, but it is the same as bar 10 with the first note taken out, so we can practice it this way.

This is a very important part of Arabic music and oud music playing. Although it may seem that it should be a central topic in a book about music oud exploration, it is only treated briefly in this book. There are few reasons for this. First, it is a large topic with very few written resources that I can find on it, and it has not been central to my own learning. Second, I feel that an over emphasis on it may give the wrong impression to the beginning or intermediate player.

Arabic and solo oud music playing in particular emphasizes composition and creativity, where the composer is not separate from the player but where composition and oud playing are meant to go together particularly in this form which is called ,in Arabic, Takasim. There is an emphasis in this form on spontaneity, as this type of music is often not repeated and is said to be composed in the moment of performing.

This emphasis on artistic expression is actually problematic for the beginner or amateur player if taken too literally. We think that we just need to approach the instrument with beautiful feelings and lots of imagination, and just listen for the beautiful improvisations that will even surprise us. We think we can even do this in front of an audience.

Arabic musicians sometimes feed this misconception. They often claim that they play their Takasim in the moment during performance and for the first time ever and without any preparation.

It may be mostly true and it is impossible to verify. I mean how do we know how much some one has prepared and what does it matter anyway as long as we are happy with the end result. It is also true that they have prepared for it all their life, as any music we hear and play is part of this preparation. We prepare when we listen to Arabic music, and when we practice forms such as Bashraf and Semai. We prepare for Takasim when we practice plectrum techniques. Many of the phrases are copied. The modes are the same and the modulations between them are the same types of modulations that are used in set and written pieces. Most of the learned techniques are also the same.

In Arabic, the word Taksim means division and the plural is Takasim. The emphasis when the word is used in Arabic is on division of the modes and exploring the modes. When the term is mentioned in English it is almost always translated or followed by the word improvisation so it takes a different meaning and places more emphasis on creativity and spontaneity. In the title of the chapter I used the phrase Free Form but it is only the rhythmic element that is more free. Rhythm is present of course but is much more flowing than in set pieces, in the same way that modern poetry has a more varied rhythm and rhyme than traditional poetry.

The important point is that we should practice Takasim and we should explore and improvise, but that should be part of a wider practice that includes technical exercises and set pieces.

An important practice of Takasim that you will find in the included pieces is lingering on the same note. It gives the player time to think of where to go next or the impression of doing so, and creates some suspense on where the music will move. Another important technique is the use of long silence to create tension and suspense. This usually precedes modulation. Since the included pieces are short, I did not include examples of modulation.

A common approach to a Taksim is exploring a given mode very slowly confining the playing to a small area of the oud and then moving outwards slowly then returning and emphasizing a central point or a theme. The player can also create interest by modulating to close or far away modes and moving back relatively quickly so as not to loose the feeling of the main mode. The rhythmic freedom also allows the player more scope to explore varieties of plectrum techniques, and other techniques such as very fast playing or tremolo or echoing phrases in another register, than is usually possible in a short set piece.

Practice the fast alterations between low and high G notes in bars 2-3, and the alterations between the high G and the low F# and G notes in 8-9. They provide a rhythmic and exciting contrast to the slowly developing melody.

Notice how the melody of the first four bars is confined to two strings of the instrument, and how only three notes of the scale are introduced in the first two bars. The confinement of the music to a restricted area and then slowly developing outwards is a typical characteristic of Arabic music takasim.

In bar 5 it looks like a modulation to a new mode might be starting, particularly that the long preceding silence would suggest it, but the player instead retracts after a brief introduction of the new theme to the original theme to develop that further.

In bar 10 to 14 a new and beautiful melody is briefly developed.

In bar 14 the player concludes the first section of the Taksim retracting to the lower registers.

The long notes in bars 16-17 are played with a tremolo to bring the first section of this music to an exciting end.

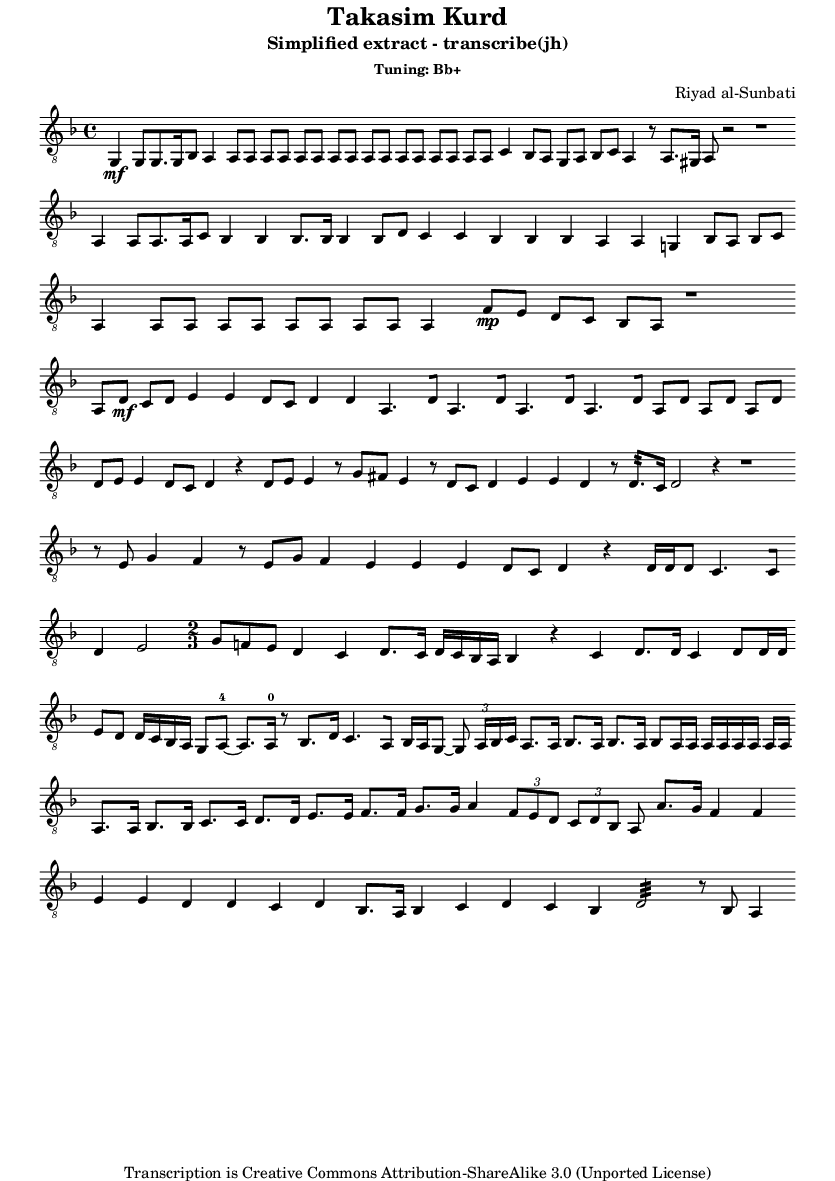

The Taksim in this extract is an example of Takasim which were often repeated in a very similar form and in recordings as they were the introduction of a song, but they are still recognizable to an Arabic audience as Takasim despite the fact that they were often repeated, and were not totally improvised during the performance.

This Taksim alternates between small sections where a clear melody can be heard, sometimes as simple as ascending a scale, and other sections where the music lingers on the same note such as the note of A or hovers between adjacent strings such as D and A or adjacent notes such as A and B.

Where the music lingers, the playing does not have to be dull. We can still create interest and tension by varying speed and volume and rhythmic pattern. You don’t have to play the notes exactly as written.

Note how a long silence precedes a modulation. Following the silence the modulation to F# is established and is distinct from the preceding section although it is brief, and a return to the note of F natural soon follows.

At this speed, this is virtuoso playing, and is only possible if the music is played softly and the plectrum is kept very close to the strings and the action is quite low such as on Turkish instruments. Try listening to the piece and practice it at half the speed or one short phrase at a time.

At such speed 1/32 notes merge into each other and become almost indistinguishable. It is more important to keep the rhythm rather than articulate each note.

The piece is a very short example of a Turkish Taksim style. It is not expected the learner player is able to duplicate it on an Arabic oud. It is sufficient here to understand the Turkish style and how it is different from the Arabic style of playing.

The tempo in most Arabic classical music forms such as Bashrafs and Rast is slow. Most vocal Arabic music from a previous era also reflects the relaxed and slow pace of life of that time and is rarely fast. There is a strong temptation when playing the oud at a beginner or intermediate level to push the music along and to gain speed as we play. This happens for various reasons such as trying to embellish or fill in music that seems to be bare without harmony, by skipping and not counting silence correctly or panicking when seeing faster notes. All of these are common problems.

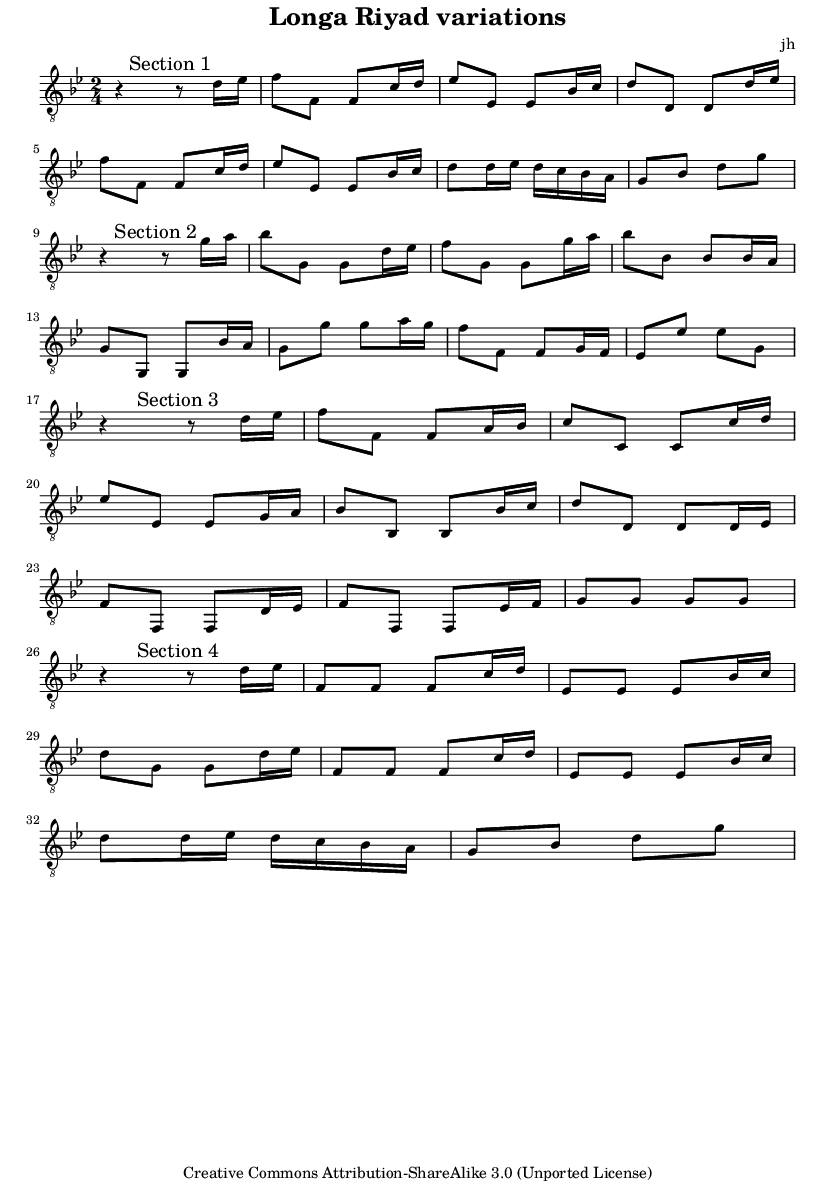

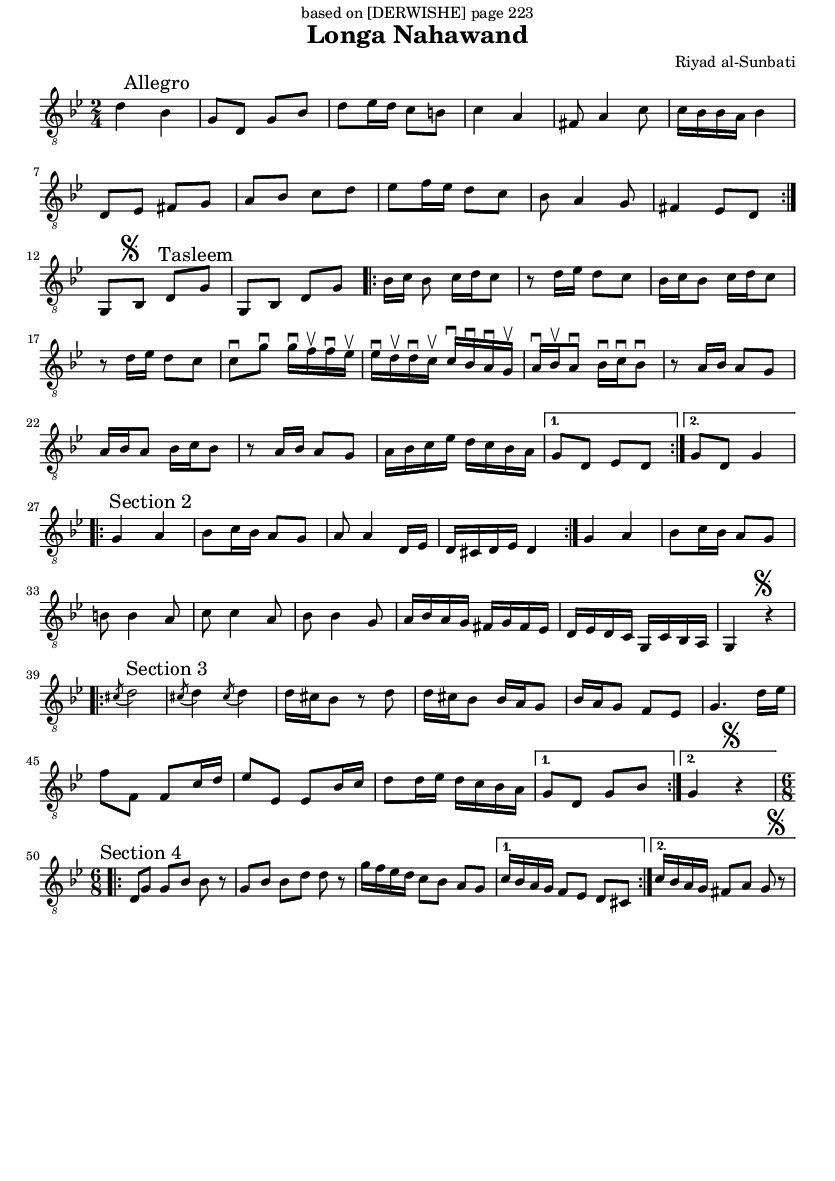

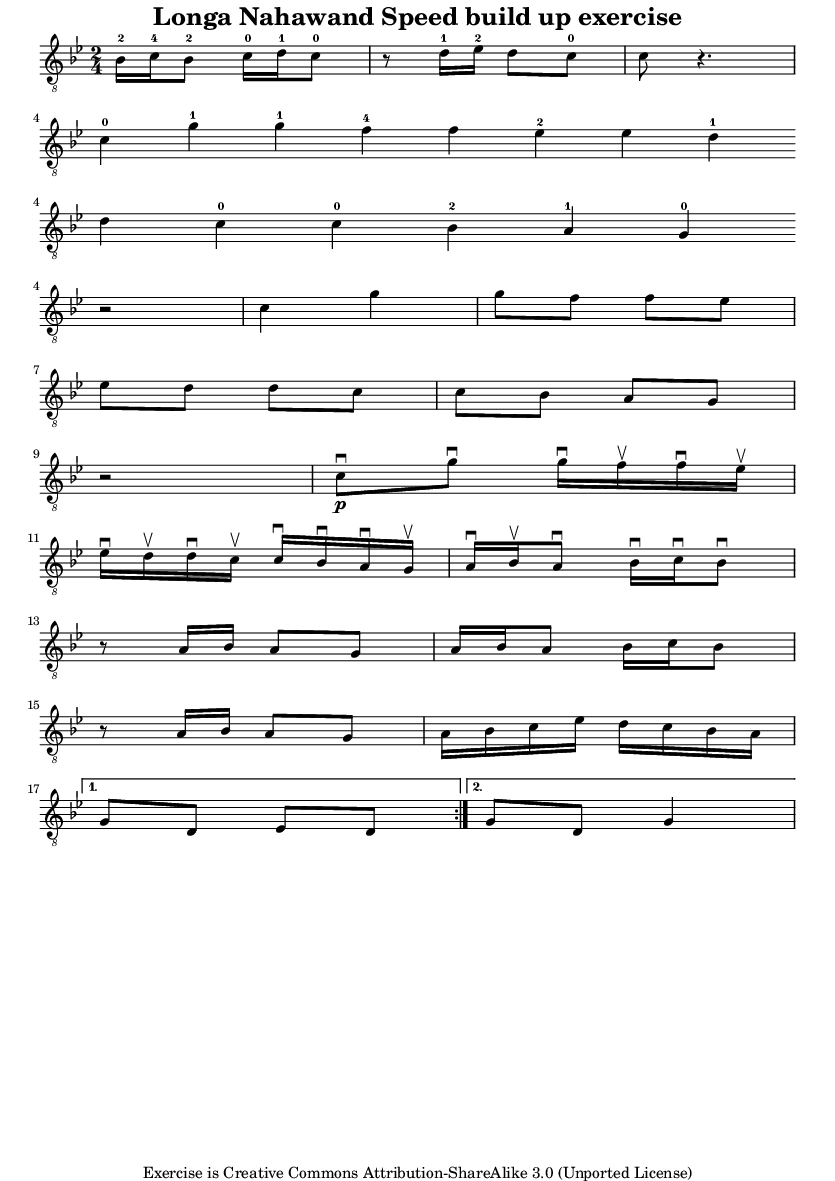

So the problem is not usually playing too slow but playing too fast. In the Longa form, which is a Turkish form, the style of the music pushes us to play faster. So we must push ourselves here but not so much that we lose control of the piece, although that is also alright during practice as the only way to be able to play faster is to keep trying to do it every now and then.

There are several ways that we can fit more notes in without expanding more effort. We can do that by playing softer as that requires less energy. We can keep the plectrum as close to the strings as possible and play up and down strokes and avoid too many string crossings.

There are two common techniques of practicing a piece that we find too fast to play in time. We can slow the tempo of the whole piece and increase the speed gradually to the required tempo. This works up to a point as slowing the music too much would make us lose the feeling of the piece. The second technique is to play at full speed or near full speed a much shorter burst or section of the music and then gradually add in more surrounding notes.

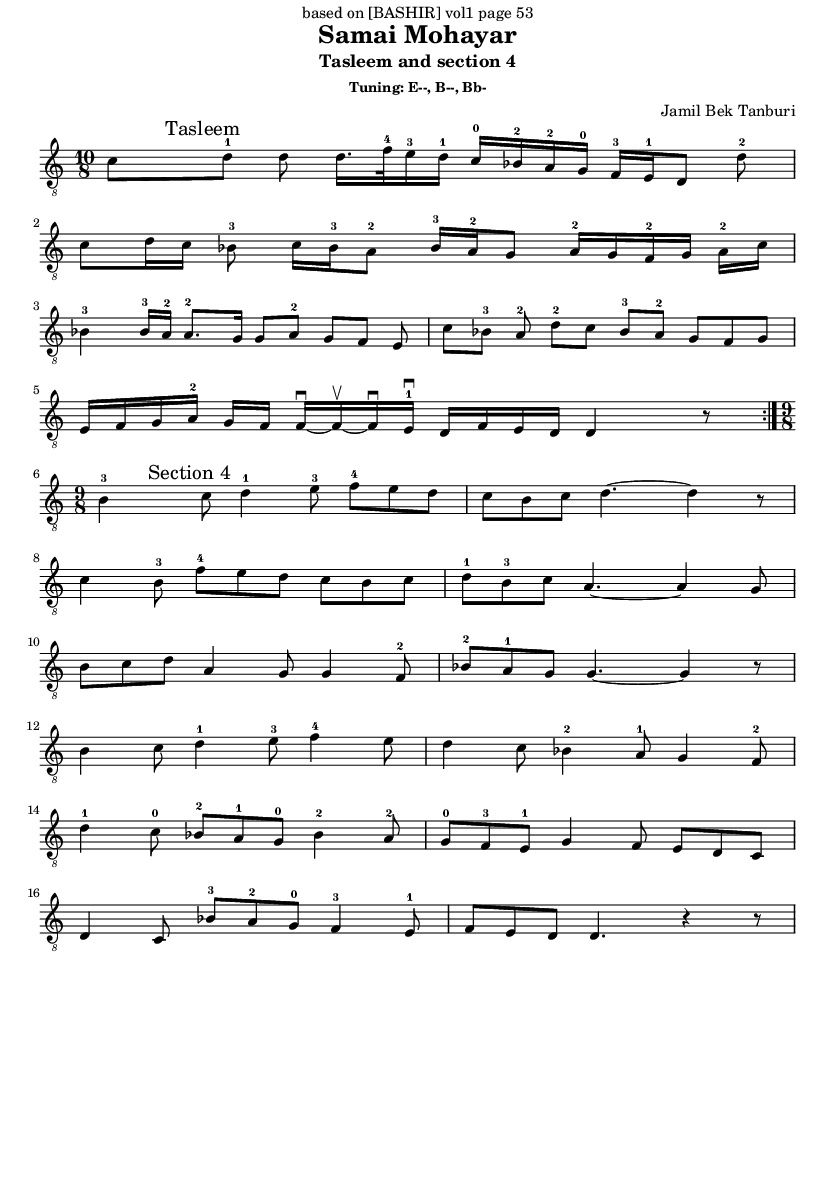

The piece is not particularly fast overall, but some runs in it can be quite fast at an allegro tempo and these should be practiced separately at a slower tempo. In particular the difficult run of notes in the tasleem in bars 18-20, 36-37 and 52-53.

Experiment using a closed finger position in bars 6, 14 and 36 to avoid crossing the string for only one note at high speed.

Pay attention to the brief silence at the start of bars 15, 17 and 23. If you are tapping your foot, you should not be playing when the foot touches the ground in these bars but when the foot is in its highest position. Try these bars in a slower tempo.

Practice the switch between lower and higher registers in bars 11-14. Play the broken chord in bar 12 using only down strokes, and avoid any unnecessary lifting of the left hands fingers, as the notes of the chord are repeated.

Try some of the suggestions in the speed build up exercise that follows this piece before trying it again at full speed.

The G note tends to be the lowest note played in most oud melodies. There are lower notes such as the F note when the fifth string is tuned to F and other notes that can be played on the lowest 6th string but these tend to be used not as part of the melody but to emphasize the mode: playing a drone or echoing important notes and phrases. It is possible to start a G scale on the second string of the oud which is tuned to this note, but in a traditional oud we will end up playing too many sections near the neck of the oud as we run out of strings so that is not practical for most players.

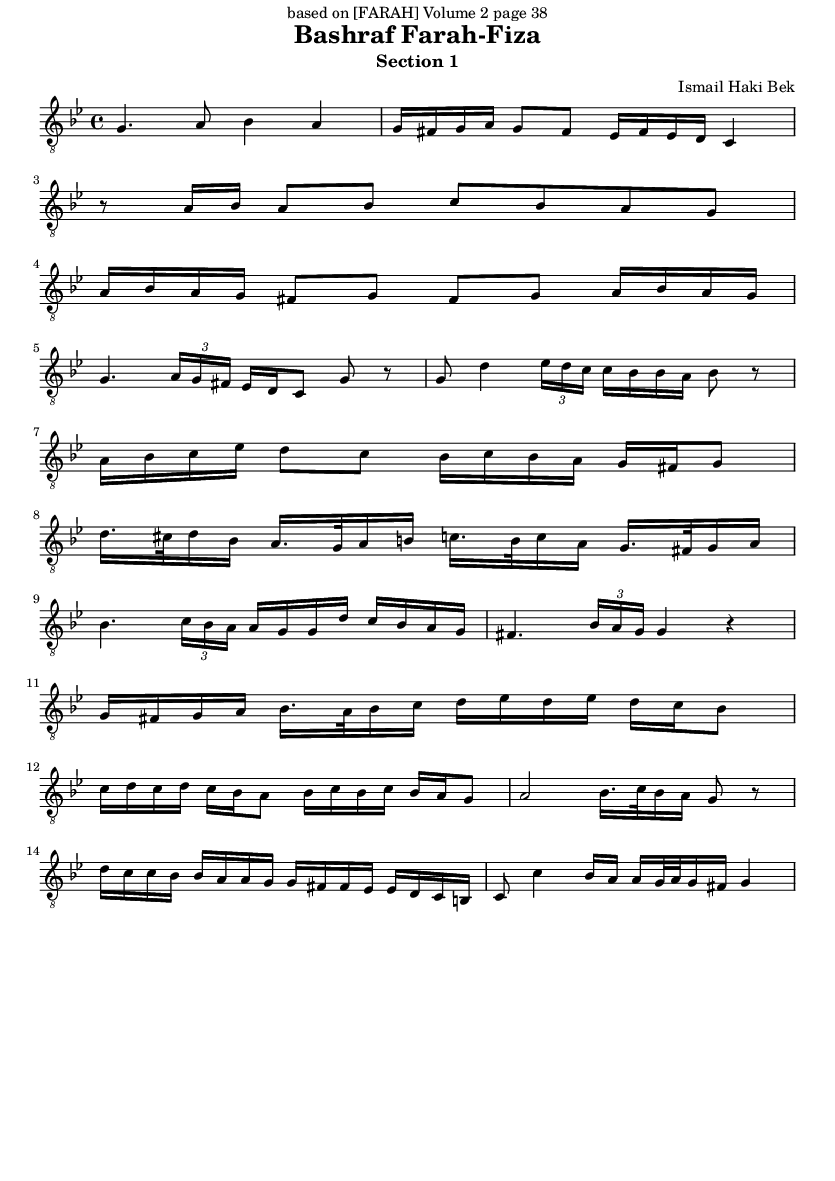

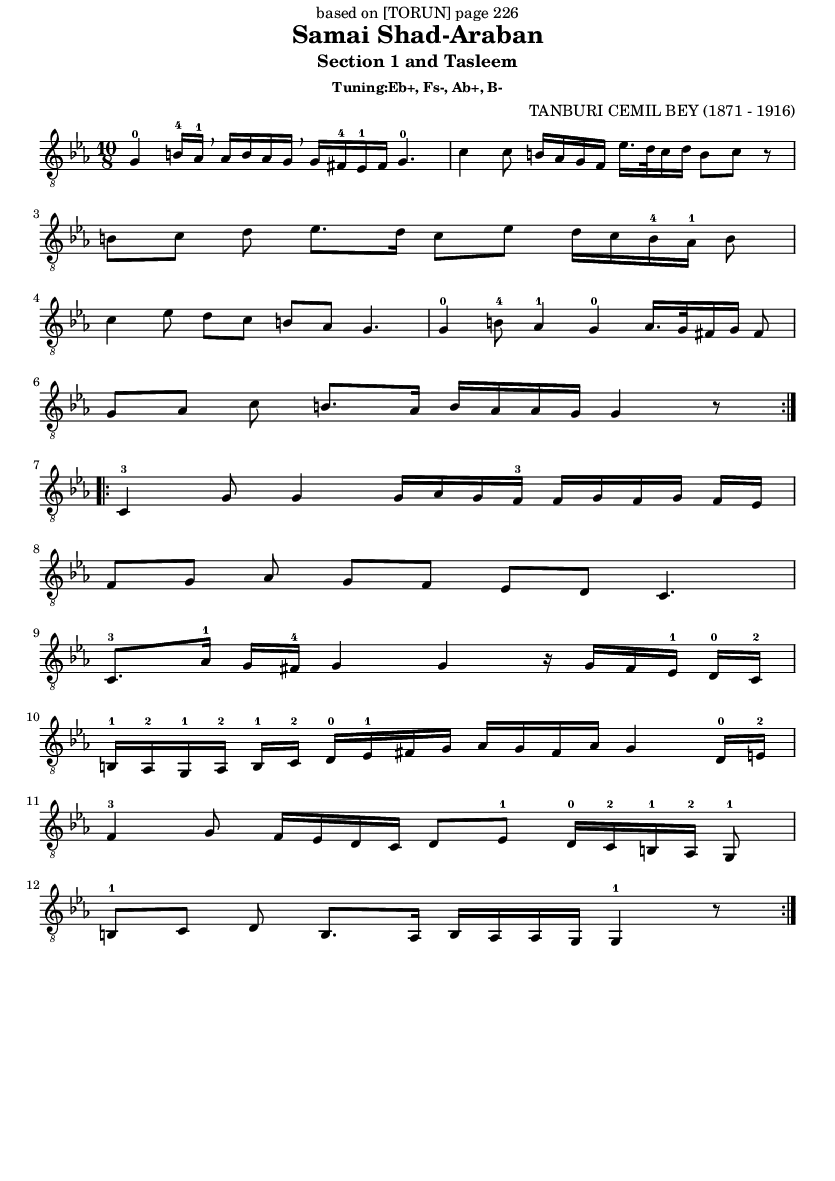

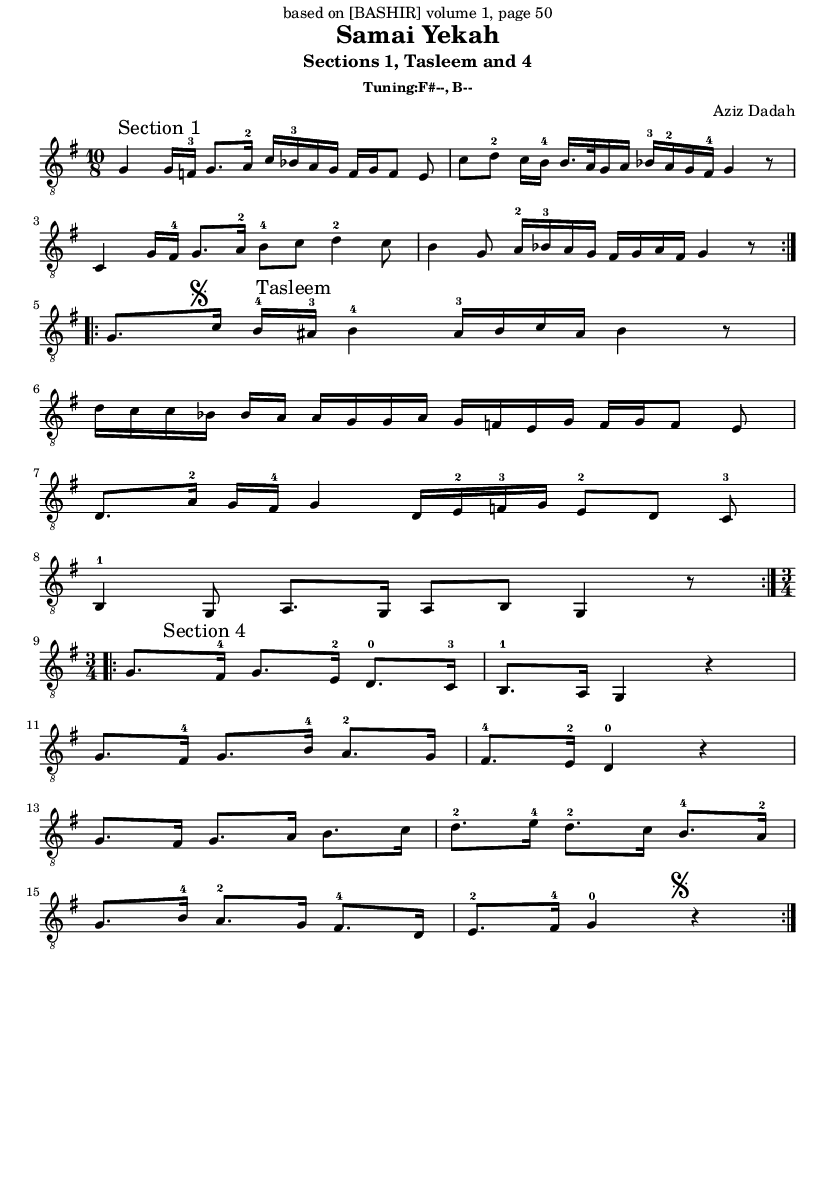

So, only few modes start on lower G and they tend to be modulations of the modes that are started 4th above on the note of C.

For example Farah-Fiza (or Farah-Faza) can be thought of a modulation of Nahawand, although it has its own atmosphere. Nahawand has similar scale notes to C minor and Farah Fiza has similar notes to G minor. Shad-Araban is a modulation of Hijaz-Kar Kurd. It can be possibly played on a piano like C minor or G minor but the 1.5 tone interval of these modes in Arabic or Turkish music are somewhat smaller than 1.5 notes as the two distant notes are brought a little closer together. So if it is played on the piano, it will sound close but not quite right. Yega or Yeka is a modulation of Rast. It has a unique Arabic and another Unique Turkish sound where the third interval between the first and third notes is somewhat larger than 1.5 tone and less than 2 tones , so it is neither minor or major but somewhere in between. These modes with roughly 3/4 intervals cannot be played correctly on a piano.

Despite these modes on G being theoretically modulations of C modes, they all have their distinct character and melodic development. They tend to be more relaxed and more sad. I only included in this chapter small samples of pieces for some of the important modes, and I leave it up to the reader to explore more pieces in any of the presented modes.

The most common mistake I do with this piece is to start too fast. Then the 1/16 notes and the triplets and eventually the 1/32 note in bar 15 will need to be played at a super fast speed. The tempo in this piece is not indicated but try it at a tempo of 60 beats per minute, or even a slower tempo that you are comfortable with.

A new and distinct musical phrase starts in bar 8. Even though there is no preceding break, take a breath and slow down a little if you did speed up previously. The uneven rhythm between the dotted 1/16th notes and following 1/32 notes needs to be brought out clearly.